Author: Emilie E. Palmer

Date: 8 July 1859

Location: Emilie E. Palmer 1859 Diary, Record Group 19/2, Oberlin College Archives

Document Type: Autograph Document

Introduction:

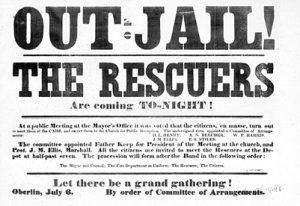

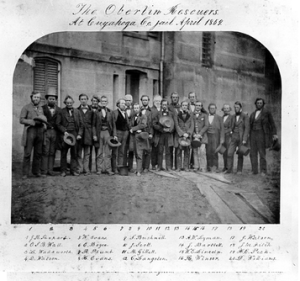

Palmer details the town-wide celebration of the return of thirty-seven previously imprisoned men for their role in the Rescue of fugitive John Price, the culmination of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue marked a watershed moment wherein the town challenged the collectively despised Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The excitement Palmer witnesses upon the return of the Rescuers fully demonstrates the determination of the Oberlin community to fight injustice and celebrate those who aid the abolitionist effort.

On 13 September 1858, Shakespeare Boyton, the son of a wealthy Oberlin landowner, was sent by Kentucky slave catchers to persuade John Price to work as a farmhand for his family as a scheme to reveal Price as a fugitive. Later that day, immediately following the abduction of John Price, a mob of Oberlin men stormed the hotel in nearby Wellington, Ohio which held Price, and successfully freed him from his the slave catchers. Police arrested thirty-seven Oberlin men for their participation in the event. Two men, Charles Langston and Simeon Bushnell, were tried and convicted for violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.1 After the Kentucky slave catchers were themselves captured and arrested for kidnapping in 1859, charges against all parties were dropped. In this entry, Palmer recounts her experience watching the Rescuers return to Oberlin and joining in the town festivities.

This document reveals the political sentiments of the town and its inhabitants on the eve of the Civil War. A staunchly abolitionist town known for its participation in the Underground Railroad and its willingness to harbor fugitive slaves, Oberlin was ready to resist the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In his first-hand account of the incidents, published as The History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, Jacob Shipherd writes, “it was well the blow had fallen where it did— upon a community who had the boldness to meet it, the fortitude to endure it, and the discretion to act in such a manner as to result in the triumph they had met to rejoice over.”2

Document Text:

About noon today, news came that “The rescuers[”] were pardoned, and were coming home on the evening train. There was joy in Oberlin such as is not witnessed every day. At prayers notice was given of the meeting in the evening and one of the Professors said that Mrs. Dascomb3 gave the ladies permission to attend, and also if any of them felt strongly moved they might go with the procession to the depot. I think some of them must have been moved for nearly all the students were with the three thousand who assembled to welcome the heroes home; when they alighted from the cars a shout arose that made Oberlin sing, Prof Monroe4 was called out and from the platform pronounced an eloquent and thrilling speech in welcome of the prisoners. The procession then formed, with Father Keep5 + Father Gillett in advance, and the vast throng with banners flying moved to the stirring music of the Oberlin band towards the church. As “the prisoners” marched up the path towards the noble edifice, the fire companies dressed in uniform opened to right and left and with heads uncovered received the “Rescuers” with a right hearty greeting. The vast church was in a moment

About noon today, news came that “The rescuers[”] were pardoned, and were coming home on the evening train. There was joy in Oberlin such as is not witnessed every day. At prayers notice was given of the meeting in the evening and one of the Professors said that Mrs. Dascomb3 gave the ladies permission to attend, and also if any of them felt strongly moved they might go with the procession to the depot. I think some of them must have been moved for nearly all the students were with the three thousand who assembled to welcome the heroes home; when they alighted from the cars a shout arose that made Oberlin sing, Prof Monroe4 was called out and from the platform pronounced an eloquent and thrilling speech in welcome of the prisoners. The procession then formed, with Father Keep5 + Father Gillett in advance, and the vast throng with banners flying moved to the stirring music of the Oberlin band towards the church. As “the prisoners” marched up the path towards the noble edifice, the fire companies dressed in uniform opened to right and left and with heads uncovered received the “Rescuers” with a right hearty greeting. The vast church was in a moment  crowded to its utmost capacity and less than 3,000 persons were present and more than half of them young men and women. As the prisoners walked up the aisle, each was presented by some fair hand with a beautiful wreath. The pulpit was decorated and all the “Rescuers” with many of their friends were seated in the rostrum. Father Keep took the chair at just eight o’clock. After prayers he addressed the audience, his speech was short and pithy. Hon. Ralph Plumb6 next addressed us. He read some extracts from the Plain Dealer7 which were rather laughable. He said in conclusion, “Fellow citizens it is meet that your rejoicings should be without restraint for our victory has been perfect complete.[“] Prof. H. E Peck8 next came forward and was received with a greeting that showed how he was beloved. He gave some of the waymarks of his life. The death of his mother, his conversion + marriage: reception of his first born: its death: the act of devotion, when, with wife and children by his side he thanked God that John9 had been rescued: his arrest: his imprisonment: his encounter with the Supreme Court: and having reviewed all there findings himself liking a part in this

crowded to its utmost capacity and less than 3,000 persons were present and more than half of them young men and women. As the prisoners walked up the aisle, each was presented by some fair hand with a beautiful wreath. The pulpit was decorated and all the “Rescuers” with many of their friends were seated in the rostrum. Father Keep took the chair at just eight o’clock. After prayers he addressed the audience, his speech was short and pithy. Hon. Ralph Plumb6 next addressed us. He read some extracts from the Plain Dealer7 which were rather laughable. He said in conclusion, “Fellow citizens it is meet that your rejoicings should be without restraint for our victory has been perfect complete.[“] Prof. H. E Peck8 next came forward and was received with a greeting that showed how he was beloved. He gave some of the waymarks of his life. The death of his mother, his conversion + marriage: reception of his first born: its death: the act of devotion, when, with wife and children by his side he thanked God that John9 had been rescued: his arrest: his imprisonment: his encounter with the Supreme Court: and having reviewed all there findings himself liking a part in this  wondrous scene. He went on to tell of some of the joys and sorrows of their prison life. The Marseillaise Hymn was then sung, by the choir. J. M Fitch10 was the next speaker. For the course of his speech he said that he had learned many lessons during eighty five days imprisonment and if he was as successful in reciting them as he had been in learning he thought he should receive a six. John Watson11 was next called out. The evening was by this time far spent and Father Keep resigned the choir to Prof. Monroe. He informed the audience that Mr. Hoss of Elyria would give them some account of how the Kentuckeyans did not succeed in E— and how the writ wasn’t served. His speech was full of cutting witticisms and called forth shouts of applause. He told how Judge D— was advised to visit his friends in Painsville, whom they all knew he had neglected very much of late so he took a very early start and thus unfortunately avoided the Kentuckyans. He said he had come there to see the twelve men who stood up so boldly for freedom with no “nolle contendre”12 to dim the lustre of their fame. H.W. Lincoln13 was next called out and was warmly received by his fellow students and the audience generaly. Prof. Monroe next introduced the subject of clapping the hands. He spoke of H.W Beechers14 views and said he would suggest a new kind, namely copping their hands in their pockets. [-inserted above the line in pencil: A collection was then taken up.] John Scott15 a colored man next spoke briefly but well. Next H. Evans A. McLyman a student + a member of the fire department, R. Winsor also a student, Sheriff Wightman,16 Sheriff Burr,17 Mr. Bushnell,18 who remained in jail was mentioned. Mr. Monroe said we do not forget him. As my soul lives, as God lives, and as we all live, when Simeon Bushnell does come home we’ll give him a reception which will convince the tyrants that have oppresed [sic] him that there are hearts that love him. Father Gillette next arose. [-inserted above the line in pencil: and spoke briefly] The chairman then said we have given you a specimen of an honest Professor and perhaps that is not the most remarkable thing in the world. We have shown you an honest lawyer that may surprise you, but we have another specimen to present I mean an honest postmaster. He then presented Mr. H. R. Smith.19 Mr. Washburn20 was then introduced to the audience. Prin. Fairchild21 then introduced some resolutions which were unanimously adopted. Doctor Morgan then made an impressive prayer. The multitude then joined in singing Old Hundred Praise God22 from [illegible]. And then in a stillness scare to be expected in so vast a multitude, the benediction was pronounced. It was midnight before the congregation broke up. It was indeed an evening never to be forgotten.

wondrous scene. He went on to tell of some of the joys and sorrows of their prison life. The Marseillaise Hymn was then sung, by the choir. J. M Fitch10 was the next speaker. For the course of his speech he said that he had learned many lessons during eighty five days imprisonment and if he was as successful in reciting them as he had been in learning he thought he should receive a six. John Watson11 was next called out. The evening was by this time far spent and Father Keep resigned the choir to Prof. Monroe. He informed the audience that Mr. Hoss of Elyria would give them some account of how the Kentuckeyans did not succeed in E— and how the writ wasn’t served. His speech was full of cutting witticisms and called forth shouts of applause. He told how Judge D— was advised to visit his friends in Painsville, whom they all knew he had neglected very much of late so he took a very early start and thus unfortunately avoided the Kentuckyans. He said he had come there to see the twelve men who stood up so boldly for freedom with no “nolle contendre”12 to dim the lustre of their fame. H.W. Lincoln13 was next called out and was warmly received by his fellow students and the audience generaly. Prof. Monroe next introduced the subject of clapping the hands. He spoke of H.W Beechers14 views and said he would suggest a new kind, namely copping their hands in their pockets. [-inserted above the line in pencil: A collection was then taken up.] John Scott15 a colored man next spoke briefly but well. Next H. Evans A. McLyman a student + a member of the fire department, R. Winsor also a student, Sheriff Wightman,16 Sheriff Burr,17 Mr. Bushnell,18 who remained in jail was mentioned. Mr. Monroe said we do not forget him. As my soul lives, as God lives, and as we all live, when Simeon Bushnell does come home we’ll give him a reception which will convince the tyrants that have oppresed [sic] him that there are hearts that love him. Father Gillette next arose. [-inserted above the line in pencil: and spoke briefly] The chairman then said we have given you a specimen of an honest Professor and perhaps that is not the most remarkable thing in the world. We have shown you an honest lawyer that may surprise you, but we have another specimen to present I mean an honest postmaster. He then presented Mr. H. R. Smith.19 Mr. Washburn20 was then introduced to the audience. Prin. Fairchild21 then introduced some resolutions which were unanimously adopted. Doctor Morgan then made an impressive prayer. The multitude then joined in singing Old Hundred Praise God22 from [illegible]. And then in a stillness scare to be expected in so vast a multitude, the benediction was pronounced. It was midnight before the congregation broke up. It was indeed an evening never to be forgotten.

Mr. Chadwick23 accompanied me home, we had some little fun before starting.

Transcribed by Katherine Graves

1 Charles Henry Langston (1817-1892) and his younger brother John Mercer Langston (1829-1897) were instrumental in making Oberlin an abolitionist center. Both attended the Convention of Colored Citizens of Ohio in 1852, at which Sojourner Truth was present, jointly demanding the strengthening of education for African Americans. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was the focus of their outrage, as they could be taken into slavery, and their freedom was only protected by the witness of a sympathetic white person. Charles Langston was the first African American graduate of Oberlin College in 1835, and married Mary Jane Patterson, the first African American woman to receive a BA Degree from Oberlin College in 1862. (J. Brent Morris, Oberlin, Hotbed of Abolitionism: College, Community, and the Fight for Freedom and Equality in Antebellum America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 168).

2 Jacob, Shipherd, The History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, (Massachusetts: Boston, 1859), 275.

3 Marianne P. Dascomb (1812-1879) was the principal of the female department of Oberlin College from 1835 to 1836 and from 1852 to 1870. (“Two Noted Women in History of Oberlin,” The Oberlin News-Tribune. (1935), Web address, accessed 15 March 2015).

4 James Monroe (1821-1898), a professor of Rhetoric and Belles Letters, was an alumnus of the college who supported both abolitionist and temperance movements. (James Monroe, Oberlin College Archives Historical Portraits, Web address, accessed 12 March 2015).

5 Reverend John Keep (1781-1870) served as an Oberlin College Trustee from 1834 to 1870 and cast the deciding vote to admit black students to the college in 1835. (“Reverend John Keep (1781-1870),” Oberlin College Archives Historic Portraits, Web address, accessed March 15, 2015).

6 Ralph Plumb (1816-1903) was a lawyer who attempted to free Price through legal methods. Additionally, he co-wrote the book History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue with Jacob Shipherd. (Jacob Shipherd, The History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, 278).

7The Plain Dealer was a Cleveland newspaper, which in 1859 reported on the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. The 6 July 1859 article states, “So the government has been beaten at last, with law, Justice, and facts on all its side, and Oberlin, with its rebellious Higher Law creed is triumphant. The precedent is a bad one.” This excerpt shows the Democratic backlash against civil disobedience and abolition, likely what Palmer dismisses as “laughable.” The Plain Dealer was not the only newspaper to report unfavorably on the Rescue; The Lorain County Eagle (Dem.) said on 13 July 1859, “The Republicans are making some very silly attempts to convince somebody that the Oberlinites have achieved a great triumph, and that the Government has ‘backed down,’ or something. … The law was enforced, Bushnell and Langston were tried, convicted and imprisoned. Thus far the triumph seemed to be altogether with the government. … The Government has succeeded in punishing them all in the same degree as far as imprisonment is concerned and it is safe to conclude that such a miserable set of hairbrained fanatics have nothing to pay fines with … Then where is the backing down?’” (Elbert Jay Benton and William Cox Cochran, The Western Reserve and The Fugitive Slave Law: A Prelude to the Civil War. Publication no.101. Collections. The Western Reserve Historical Society, 200).

8 Henry Everard Peck (1821-1867) was Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy at the college from 1851 to 1865. He was a staunch abolitionist who spent 85 days in jail with the other Rescuers. (“Henry Everard Peck,” Lorain County News, Web address, accessed 17 March 2015).

9 John Price, the young black fugitive who was forcibly taken to Wellington by Kentucky slave catchers, rescued by a crowd of men from Oberlin, and sequentially escaped to Canada. (“The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue,” Electronic Oberlin Group, Web address, accessed 17 March 2015).

10 James M. Fitch, one of the Rescuers, was a bookseller and Sunday school superintendent who lived in Oberlin. (“James M. Fitch,” Oberlin College Archives Historic Portraits, Web address, accessed 15 March 2015).

11 John Watson, the first Rescuer to arrive in Wellington, was a store-owner in Oberlin. (Liz Schultz, Roland Baumann, Gary Kornblith, and Mary Moroney, “Oberlin-Wellington Rescue 1858,” Oberlin Heritage Center, Web address, accessed 12 March 2015).

12 A plea by which a defendant in a criminal prosecution accepts conviction, as in the case of a plea of guilty, but does not admit guilt. “nolo contendere, n.1.” 23 June 2015.

13 H.W. Lincoln was a student of Oberlin College, enrolled in 1857, from Oberlin, OH. (Annual Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Oberlin College for the College Year 1857-1858. (Ohio: Oberlin, 1857)).

14 Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887), brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe, was a staunch abolitionist and feminist who contributed to the New York Ledger and wrote one novel, Norwood. (“Henry Ward Beecher – Norwood (1867),” Old And Sold, Web address, accessed 18 March 2015).

15 John Scott, one of the Rescuers, was a harness and trunk maker in Oberlin. (Liz Schultz, Roland Baumann, Gary Kornblith, and Mary Moroney, “Oberlin-Wellington Rescue 1858,” Oberlin Heritage Center, Web address, accessed 12 March 2015).

16 Sheriff Wightman oversaw the imprisonment of the Rescuers (Wilbur Greeley Burroughs, “Oberlin’s Part in the Slavery Conflict,” Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, 20, no. 1 (1911): 269-332, Web address, accessed 12 March 2015).

17 Sheriff Burr, an alumnus of Oberlin College, was a Lorain County sheriff who caught the four Kentucky slave catchers who captured Price. (Ron Gorman, “‘Odious Business’ in Oberlin: Northern States’ Rights, Part 3.” Oberlin Electronic Group. Web address, accessed 1 July 2015).

18 Simeon Bushnell was a bookseller from Oberlin who was one of the two men, along with Charles Langston, who were convicted and sentenced for breaking the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 because of their actions rescuing Price. (“Oberlin-Wellington Rescue Case,” Ohio History Central, Web address, accessed 9 March 2015).

19 Henry R. Smith, originally from Sarahsville, OH, was a student enrolled in the college in 1868. (Catalogue of Oberlin College for the Years 1868-1869. (Ohio: Cleveland, 1868)).

20 George G. Washburn was an editor of the Elyria Democrat who gave a stirring abolitionist speech to the crowd. (Jacob Shipherd, The History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue (Massachusetts : Boston, 1859)).

21 James Harris Fairchild (1817-1902) was president of Oberlin College from 1866 to 1889. (James Harris Fairchild, Oberlin College Archives, Web address, accessed 12 March 2015).

22 “Old Hundred” was a popular biblical hymn. “Praise God” refers to its opening lyrics. (“Old Hundredth,” Hymnary.org, Web address, accessed 17 March 2015).

23 Likely Leroy L. Chadwick, Oberlin College student pursuing Latin from Perrysburg, NY. (Annual Catalogue 1859-1960, Account 0/00/1, RG College General, Box 4, Catalogs, 1855-1863, Oberlin College Archives).