|

|

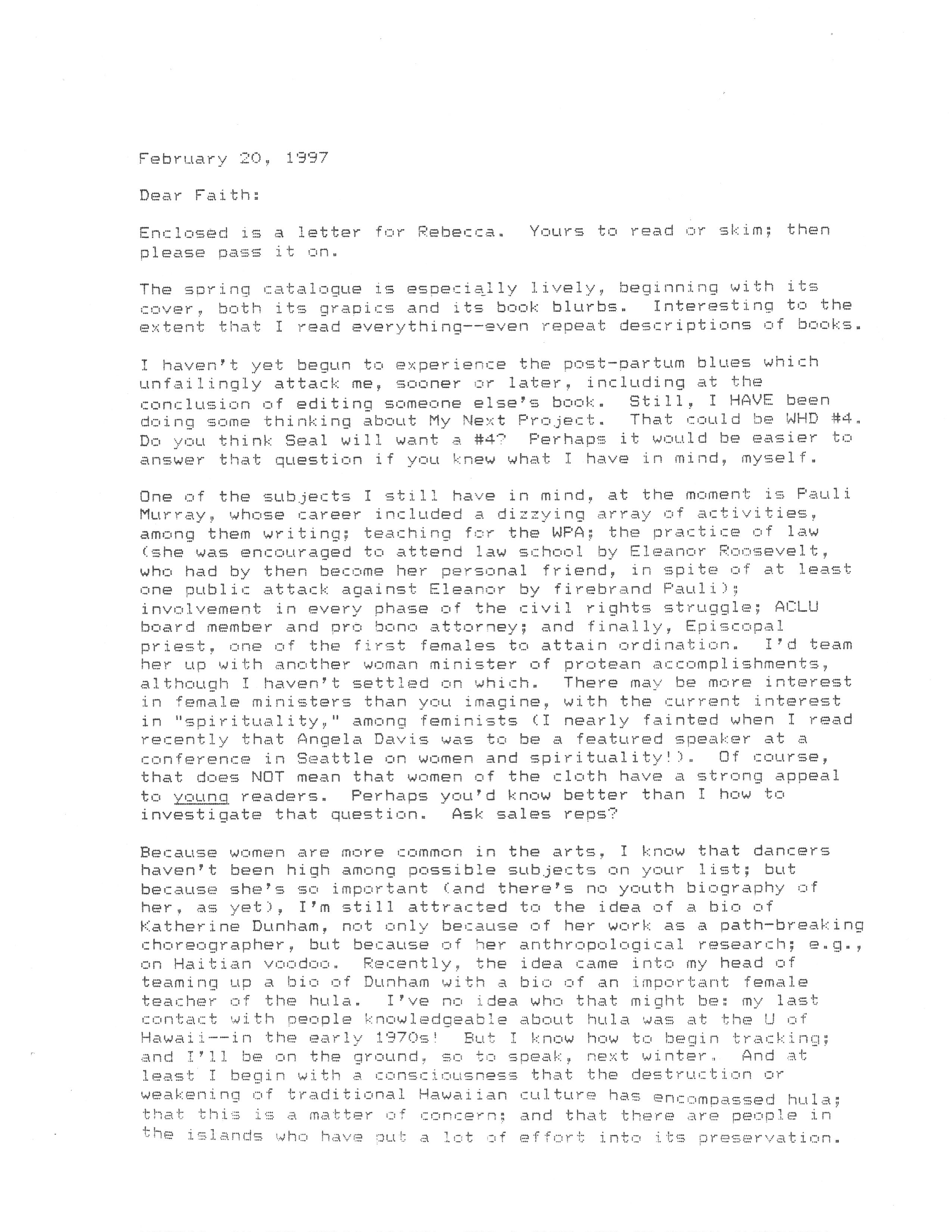

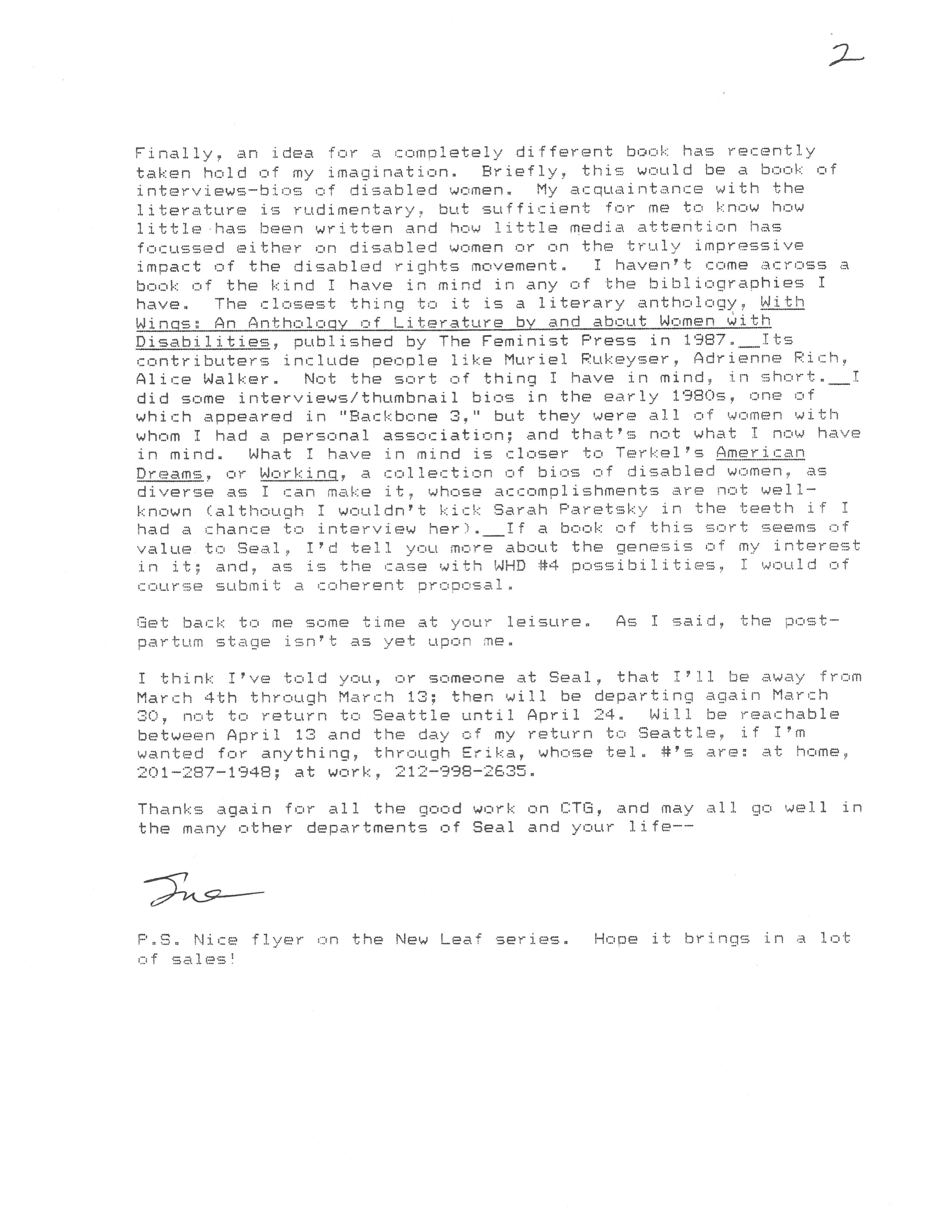

Transcription: February 20, 1997 Dear Faith: Enclosed is a letter for Rebecca.[2] Yours to read or skim; then please pass it on. The spring catalogue is especially lively, beginning with its cover, both its graphics and its book blurbs. Interesting to the extent that I read everything–even repeat descriptions of books. I haven’t yet begun to experience the post-partum blues which unfailingly attack me, sooner or later, including at the conclusion of editing someone else’s book. Still, I HAVE been doing some thinking about My Next Project. [sic] That could be WHD #4.[3] Do you think Seal will want a #4? Perhaps it would be easier to answer that question if you knew what I have in mind, myself.  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauli_Murray#/media/File:UNCPauliMurray.png One of the subjects I still have in mind, at the moment is Pauli Murray, whose career included a dizzying array of activities, among them writing; teaching for the WPA; the practice of law[4] (she was encouraged to attend law school by Eleanor Roosevelt,[5] who had by then become her personal friend,[6] in spite of at least one public attack against Eleanor by firebrand Pauli);[7] involvement in every phase of the civil rights struggle; ACLU board member and pro bono attorney; and finally, Episcopal priest, one of the first females to attain ordination. I’d team her up with another woman minister of protean accomplishments, although I haven’t settled on which. There may be more interest in female ministers than you imagine, with the current interest in “spirituality,” among feminists[8] (I nearly fainted when I read recently that Angela Davis was to be a featured speaker at a conference in Seattle on women and spirituality!). Of course, that does NOT mean that women of the cloth have a strong appeal to young readers. Perhaps you’d know better than I how to investigate that question. Ask sales reps?  Because women are more common in the arts, I know that dancers haven’t been high among possible subjects on your list; but because she’s so important (and there’s no youth biography of her, as yet), I’m still[9] attracted to the idea of a bio of Katherine Dunham,[10] not only because of her work as a path-breaking choreographer, but because of her anthropological research; e. g., on Haitian voodoo.[11] Recently, the idea came into my head of teaming up a bio of Dunham with a bio of an important female teacher of the hula. I’ve no idea who that might be: my last contact with people knowledgeable about hula was at the U of Hawaii–in the early 1970s! But I know how to begin tracking; and I’ll be on the ground, so to speak, next winter. And at least I begin with a consciousness that the destruction or weakening of traditional Hawaiian culture has encompassed hula; that this is a matter of concern; and that there are people in the islands who have put a lot of effort into its preservation.  Finally, an idea for a completely different book has recently taken hold of my imagination. Briefly, this would be a book of interviews-bios of disabled women. My acquaintance with the literature is rudimentary, but sufficient for me to know how little has been written and how little media attention has focussed [sic] either on disabled women or on the truly impressive impact of the disabled rights movement. I haven’t come across a book of the kind I have in mind in any of the bibliographies I have. The closest thing to it is a literary anthology, With Wings: An Anthology of Literature by and about Women with Disabilities, published by The Feminist Press in 1987. __Its [sic] contributors include people like Muriel Rukeyser, Adrienne Rich, Alice Walker. Not the sort of thing I have in mind, in short. __I did some interviews/thumbnail bios in the early 1980s, one of which appeared in “Backbone 3,”[12] but they were all of women with whom I had a personal association; and that’s not what I now have in mind. What I have in mind is closer to Terkel’s[13] American Dreams,[14] or Working,[15] a collection of bios of disabled women, as diverse as I can make it, whose accomplishments are not well-known (although I wouldn’t kick Sarah [sic] Paretsky[16] in the teeth if I had a chance to interview her). __If [sic] a book of this sort seems of value to Seal, I’d tell you more about the genesis of my interest in it; and, as is the case with WHD #4 possibilities, I would of course submit a coherent proposal. Get back to me some time at your leisure. As I said, the post-partum stage isn’t as yet upon me. I think I’ve told you, or someone at Seal, that I’ll be away from March 4th through March 13; then will be departing again March 30, not to return to Seattle until April 24. Will be reachable between April 13 and the day of my return to Seattle, if I’m wanted for anything, through Erika, whose tel. #’s are: at home, [phone number redacted]; at work, [phone number redacted]. [Signed: Sue]

Transcribed by Natalia Shevin |

[1] This description was written in a letter to Janelle Stovall of the Katherine Dunham Center for Arts and Humanities (Letter to Jeanelle Stovall from Sue Davidson, 6 October 1997, Box 1: File 18, Correspondence: Sue Davidson, 1997-1999, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[2] Unable to identify.

[3] “Women Who Dared” #4.

[4] Murray pioneered the field of gender-based discriminatory law, particularly with its intersection with race, using “Jane Crow” to describe the system of race and gender injustice written into the law. Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Ruth Bader Ginsburg cited Murray’s work on her decision of Reed v. Reed, which ended sex discrimination in estate agreements (Serena K. Mayeri, “Two Women, Two Histories: A feminist, an antifeminist, and their exercise of power,” Harvard Magazine, November-December 2007, web access, accessed 28 June 2016).

[5] Murray credited her as the “Mother of the Women’s Revolution” at the 1984 conference dedicated to Roosevelt. However, forty years earlier, neither woman saw herself as part of a larger feminist movement: Murray had written Roosevelt in 1942, “If there ever were a Woman’s Revolution, I’m afraid you’d have to run for President.” (Patricia Bell-Scott, Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 357; 100).

[6] Murray and Roosevelt’s friendship was unexpected; they met at Camp Tera, a recreational camp for women during the Great Depression. Murray was a WPA recipient and Roosevelt visited the camp, a project she emphasized as important for the national agenda.

Their friendship always negotiated conflicts race, class, and sexuality, particularly how their identities informed their theories of change. Murray disagreed with Roosevelt’s critics who alleged colorblindness to policies during the Roosevelt administration. In 1944, Roosevelt advocated against “social equality,” because that was “‘something you have amongst friends;’” she was looking for justice that was systemic. Her rhetoric, however, sparked controversy immediately. Murray published a response to clarify Roosevelt’s statement—which could imply support for segregation—as Roosevelt’s concern for equality under the law: meaning that “equal access to public accommodations, fair housing and employment, and freedom of movement and association without discrimination,” issues to which both she and Murray would dedicate their lives to.

Their close relationship did not condone policies enacted under Roosevelt’s husband’s administration ; but this forty-year long commitment helped Roosevelt develop an understanding of the burdens that race, gender, and class oppression caused in everyday life. Her relationships, not only with Murray, reflected her dedication to lasting justice. In 1953, Roosevelt an essay for Ebony titled, “Some of My Best Friends Are Negro.” Her sentiment (the editor wrote the title), may appear contrived to a contemporary eye, but it was celebrated by many in the Black community; at her death, for example, the headline of the Black newspaper Baltimore Afro-American read, “We Have Lost a Great Friend” (Patricia Bell-Scott, The Firebrand and the First Lady, 154; 211; 316).

[7] Murray and Roosevelt’s remained friends despite their conflicting approach to change. Murray wrote to Roosevelt in 1940, “There can be no compromise on the principle of equality.” She held this view throughout her life, confronting the 1963 March on Washington organizers that the omission of Black women’s rights from their agenda was disgraceful—even regressive—given that William Lloyd Garrison and Charles Remond protested an abolition conference because of their bar on women delegates. But Roosevelt believed in patient politics, advocating for gradualism, as when defending the candidacy of Adlai Stevenson. Gradualism, she said, “doesn’t mean you do nothing, but it means that you do the things that need to be done, according to priority.” (Patricia Bell-Scott, The Firebrand and the First Lady, 54; 323; 253).

[8] One example is Luisah Teish’s description of spirituality and vodun, “Religion under patriarchy has been a tool of oppression. The loving and healing matristic qualities of the feminine principle have been shrouded in obscure symbolism or denied altogether. My position on feminist spirituality is borne, not out of a bourgeois intellectualism, but out of the experiences of a grassroots woman who participated fully in the struggle for the liberation of Black people” (Luisah Teish, “Women’s Spirituality: A Household Act” in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, ed. Barbara Smith (New York: Kitchen Table Women of Color Press, 1983).

[9] Davidson continued to pursue her interest in writing a biography about Katherine Dunham. On 29 October 1997, she wrote Faith Conlon, “I find it personally distressing that Dunham, who broke the path leading to Alvin Ailey and all others who have used African dance, has no biographers except herself… And her LIFE has been so exciting. There’s all that voodoo stuff!–and her close relationships with every leader of Haiti of modern time; and the movies, and legit theater; and the inspiring work she’s been doing in the social wilderness of East St. Louis…” (Letter to Faith Conlon from Sue Davidson, 29 October 1997, Box 1: File 18, Correspondence: Sue Davidson, 1997-1999, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[10] Katherine Dunham was a pioneer of modern American dance, and drew on African influence. She established a company, Ballet Negre, and a school in East St. Louis that promoted community engagement (Charmaine Patricia Warren with Suzanne Youngerman, “I See America Dancing”: The History of American Modern Dance,” Brooklyn Academy of Music, DanceMotion USA, and US Department of State web access, accessed 24 June 2016).

[11] Dunham was criticized for incorporating vodun into her modern dance choreography because of its “regressive” qualities. But Dunham remained steadfast in her interest and study of it, as “she was committed to reveal to African Americans, along with other races and nationalities, the value, dignity, and beauty of African expressions.” Dunham pioneered the field of performance ethnography and transnational dance, which started a national conversation about cultural exchange which remains today (Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life (Chicago and Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 66; 71).

[12] Backbone was a series by Seal Press which began as collected writings of all genres by Northwest women. Backbone 3 featured essays, interviews, and photographs.

[13] Studs Terkel. He is an author, and oral and public historian. Given that Davidson is pitching a collection about disabled women, it is likely that she is looking to publish collected stories and writings from everyday disabled women (not necessarily leaders of organizations or faces of movements), because that was Terkel’s legacy.

[14] American Dreams: Lost and Found (New York: Pantheon, 1980).

[15] Working (The New Press, 1974).

[16] Sara Paretsky (b. 1947), novelist of detective fiction. She has worked in reproductive and social justice, pioneering the field of crime writing for women.

[17] Unclear.

[18] A flyer announcing the New Leaf series in 1984 announced that it “was born from the success of an earlier Seal Press book, Getting Free: A Handbook for Women in Abusive Relationships. Though many publishers before us had rejected the manuscript, often suggesting that battered women would never want to admit ‘their’ problem publicly by buying such a book, sales have proved them wrong. Two years after publication Getting Free has sold 22,000 copies and is still going strong. The New Leaf Series carries on the innovative combination of self-help and feminist analysis that characterized Getting Free. Some volumes will deal more specifically with the methodology of feminist therapy for women in abusive relationships, while others will continue to be directed to the battered woman herself” (“Announcing the New Leaf Series And a Special Offer,” Ephemera, Part 1 of 2, VIII: Box 1, Folder 7, Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).