|

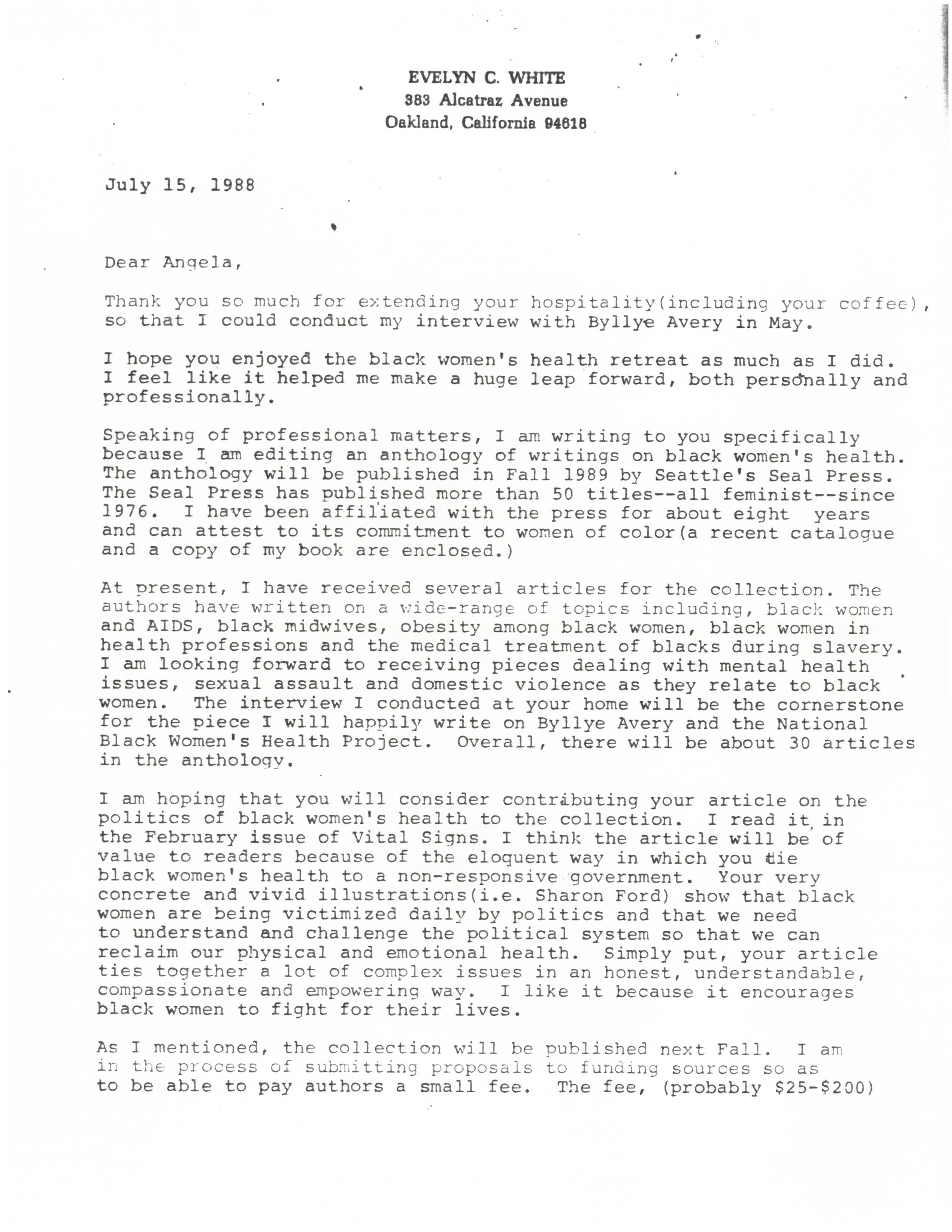

Transcription: [Letterhead: Evelyn C. White address redacted] July 15, 1988 Dear Angela,[2] Thank you so much for extending your hospitality (including your coffee), so that I could conduct my interview with Byllye Avery[3] in May. I hope you enjoyed that black women’s health retreat as much as I did. I feel like it helped me make a huge leap forward, both personally and professionally. Speaking of professional matters, I am writing to you specifically because I am editing an anthology of writings on black women’s health. The anthology will be published in Fall 1989 by Seattle’s Seal Press. The Seal Press has published more than 50 titles–all feminist–since 1976. I have been affiliated with the press for about eight years and can attest to its commitment to women of color (a recent catalogue and a copy of my book are enclosed.) At present, I have received several articles for the collection. The authors have written on a wide-range of topics including, black women and AIDS, black midwives, obesity among black women, black women in health professions and the medical treatment of blacks during slavery. I am looking forward to receiving pieces dealing with mental health issues, sexual assault and domestic violence as they relate to black women. The interview I conducted at your home will be the cornerstone for the piece I will happily write on Byllye Avery and the National Black Women’s Health Project. Overall, there will be about 30 articles in the anthology. I am hoping that you will consider contributing your article on the politics of black women’s health to the collection.[4] I read it, [sic] in February issue of Vital Signs. I think the article will be of value to readers because of the eloquent way in which you tie black women’s health to a non-responsive government.[5] Your very concrete and vivid illustrations (i. e. Sharon Ford)[6] show that black women are being victimized daily by politics and that we need to understand and challenge the political system so that we can reclaim our physical and emotional health. Simply put, your article ties together a lot of complex issues in an honest, understandable, compassionate and empowering way. I like it because it encourages black women to fight for their lives. As I mentioned, the collection will be published next Fall. I am in the process of submitting proposals to funding sources so as to be able to pay authors a small fee. The fee, (probably $25-$200) will be a pittance compared to compensation offered by mainstream publishers. We do what we can and have faith that talented committed black women writers like yourself, will reap the financial rewards you deserve. I am available should you like to discuss this project further. I [sic] any event, many thanks for the contributions you have already made to the empowerment of black women. Sincerely, [Signed: Evelyn C. White] Evelyn C. White Editor, The Black Women’s Health Anthology The Seal Press Transcribed by Natalia Shevin |

[1] “The Power of Women’s Voices,” Sophia Smith Collection: Women’s History Archives at Smith College, Smith College, web access, accessed 13 July 2016.

[2] In a letter from Evelyn C. White to Faith Conlon on 12 July 1988, three days before this letter was written, White wrote, “I will get letter off to Angela Davis and to Audre Lorde before I go to Oregon. I think the Goddess is with me on this one.”

[3] Byllye Avery (b. 1937) founded the National Black Women’s Health Project in 1984, now Black Women’s Health Imperative. In White’s final draft of the introduction to Chain Chain Change in File 29, Avery is quoted, “When sisters take their shoes off and start talking about what’s happening, the first thing we cry about is violence–battering and sexual abuse… we have to stop it because violence is the training ground for us.” (Black Women’s Health Imperative, web access, 1 July 2016; Evelyn C. White, “Chapter One, What is Domestic Violence?” File 29, Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[4] Angela Davis did contribute this essay, “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: The Politics of Black Women’s Health” for the anthology. The title is a refrain from Fannie Lou Hamer, which was also the theme of what was likely the first National Black Women’s Health Conference in 1983 at Spelman College (“The Power of Women’s Voices,” Sophia Smith Collection: Women’s History Archives at Smith College, Smith College, web access, accessed 13 July 2016).

[5] Angela Davis’ visionary thinking about the relationship between Black women and the government, and eventually the carceral state can be seen germinating in her piece “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired.”

White hoped to solicit a piece on the topic of incarceration and Black women’s health for the anthology. She wrote Faith Conlon, her editor for Black Women’s Health Book, “I have enclosed an article I recently received from a black woman who is a healthcare worker in the San Francisco jail. I like the way it is written (though it does cover some issues already in the book.) It think it is important to include something in 2 the collection that addresses the issues of incarcerated black women (since they comprise the majority of women behind bars). I think this piece does a good job of talking about the problem intelligently, honestly and concisely. Let me know what you think.” This idea became Sean Reynolds’ essay, “Bar None: The Health of Incarcerated Black Women” for the anthology. Davis would continue the legacy of writings on Black women’s incarceration, including her most famous publications on the topic, Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003) and Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture (2005) (Letter from Evelyn C. White to Faith Faith Conlon on 23 August 1989, Series II, Box 9, File 18: BWHB: New Expanded Ed. Correspondence, Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[6] Davis wrote about Sharon Ford, a “young Black woman on welfare in the San Francisco Bay Area, [who] gave birth to a stillborn child because two hospitals declined to treat her, even though she was covered by a health plan” (Angela Davis, “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: The Politics of Black Women’s Health” in Black Women’s Health Book (Seattle: Seal Press, 1990), 20).