|

|

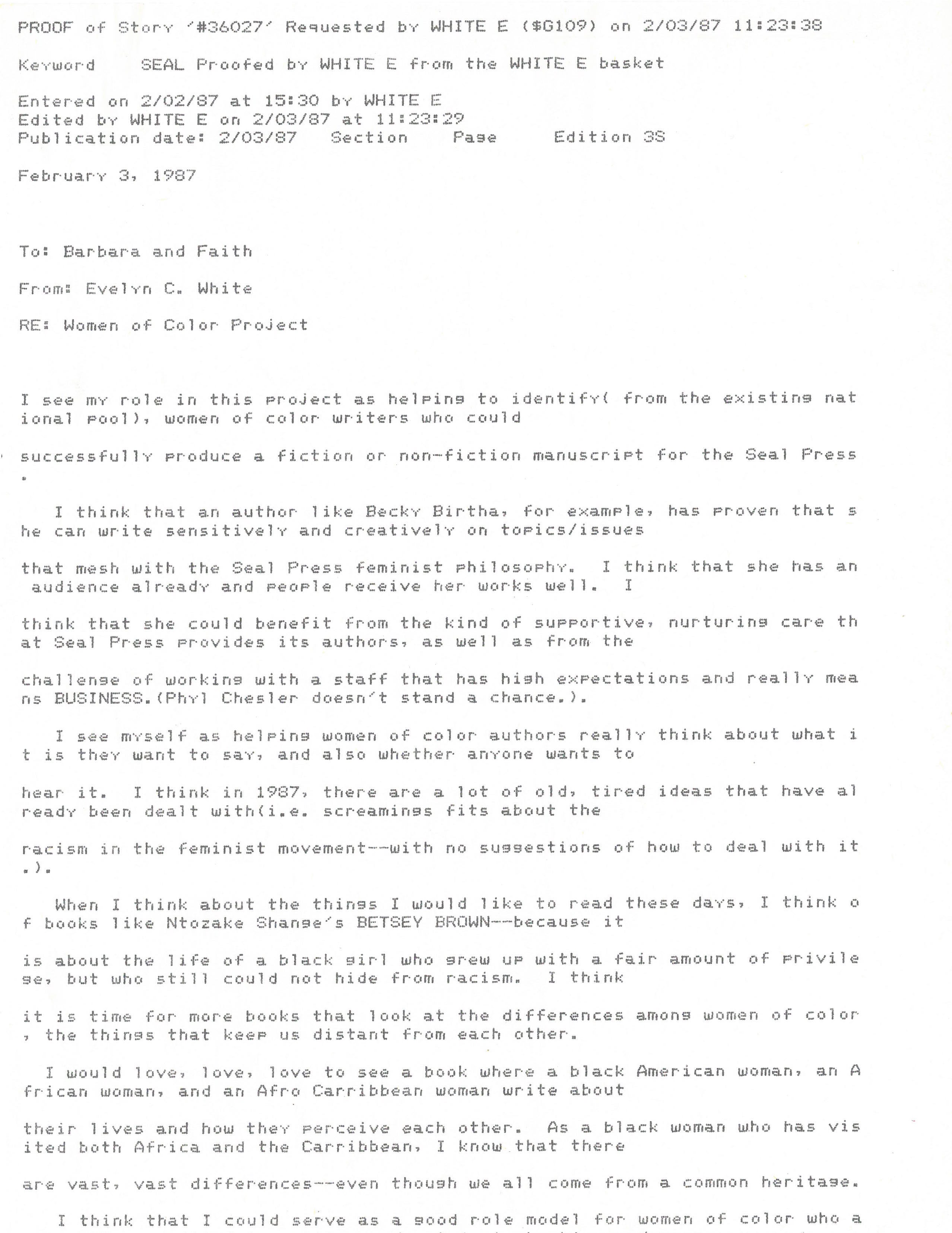

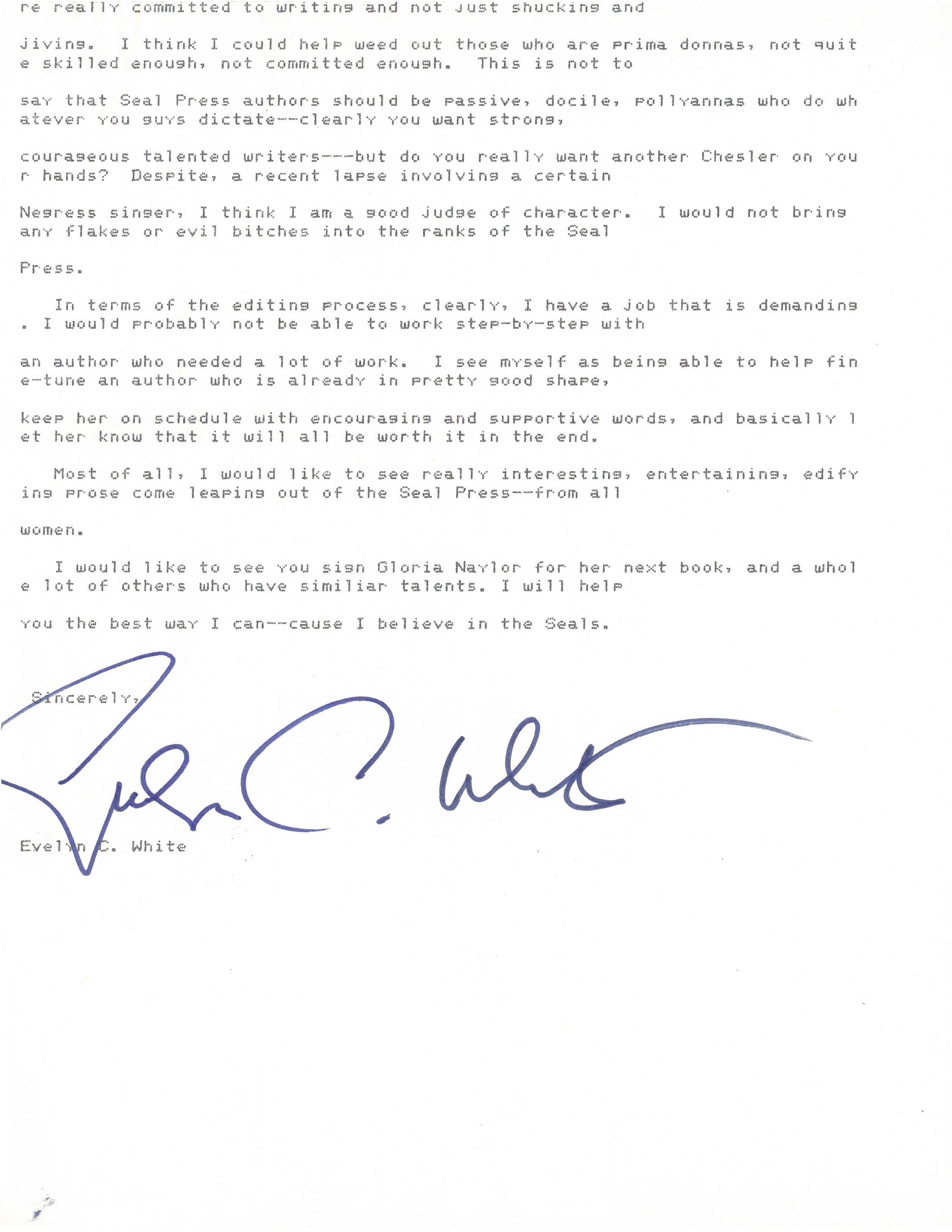

Transcription: [Computer-generated email information: PROOF of Story ‘#36027’ Requested by WHITE E ($G109) on 2/03/87 11:23:38 Keyword SEAL Proofed by WHITE E from the WHITE E basket Entered on 2/02/87 at 15:30 by WHITE E Edited by WHITE E on 2/03/87 at 11:23:29 Publication date: 2/03/87 Section Page Edition 3S] February 3, 1987 To: Barbara and Faith From: Evelyn C. White RE: Women of Color Project I see my role in this project as helping to identify (from the existing national pool), women of color writers who could successfully produce a fiction or non-fiction manuscript for the Seal Press. I think that an author like Becky Birtha,[7] for example, has proven that she can write sensitively and creatively on topics/issues that mesh with the Seal Press feminist philosophy. I think that she has an audience already and people receive her works well. I think that she could benefit from the kind of supportive, nurturing care that Seal Press provides its authors, as well as from the challenge of working with a staff that has high expectations and really means BUSINESS. ([name redacted][8] doesn’t stand a chance.). [sic] I see myself as helping women of color authors really think about what it is they want to say, and also whether anyone wants to hear it. I think in 1987, there are a lot of old, tired ideas that have already been dealt with (i. e. Screamings fits about the racism in the feminist movement–with no suggestions of how to deal with it.). When I think about the things I would like to read these days, I think of books like Ntozake Shange’s[9] BETSEY BROWN[10]–because it is about the life of a black girl who grew up with a fair amount of privilege, but who still could not hide from racism. I think it is time for more book that look at the differences among women of color, the things that keep us distant from each other. I would love, love, love to see a book where a black American woman, an African woman, and an Afro Carribbean [sic] woman write about their lives and how they perceive each other. As a black woman who has visited both Africa and the Carribbean, [sic] I know that there are vast, vast differences–even though we all come from a common heritage. I think that I could serve as a good role model for women of color who are really committed to writing and not just shucking and jiving. I think I could help weed out those who are prima donnas, not quite skilled enough, not committed enough. This is not to say that Seal Press authors should be passive, docile, pollyannas who do whatever you guys dictate–clearly you want strong, courageous talented writers—but do you really want another [name redacted] on your hands? Despite, a recent lapse involving a certain Negress singer,[11] I think I am a good judge of character. I would not bring any flakes or evil bitches into the ranks of Seal Press. In terms of of the editing process, clearly, I have a job that is demanding. I would probably not be able to work step-by-step with an author who needed a lot of work. I see myself as being able to help fine-tune an author who is already in pretty good shape, keep her on schedule with encouraging and supportive words, and basically let her know that it will all be worth it in the end. Most of all, I would like to see really interesting, entertaining, edifying prose come leaping out of the Seal Press–from all women. I would like to see you sign Gloria Naylor[12] for her next book, and a whole lot of others who have similar talents. I will help you the best way I can–cause [sic] I believe in the Seals. Sincerely [Handwritten: Evelyn C. White] Evelyn C. White Transcribed by Natalia Shevin |

[1] Intimate partner violence was a frequent topic for publishing at Seal Press, showing the gravity and pervasiveness of the issue, and unfortunately, the interest if they kept re-selling and reprinting. Seal Press published multiple iterations of self-help books for abused women, many of which were delineated by race. Myrna Z. Zambrano published Mejor Sola que Mal Accompanada: For the Latina in an Abusive Relationship (Seal Press, New Leaf Series, 1985), and a book titled Asian Battering was proposed multiple times, but it is unclear if it was ever published.

[2] White continued: “It seems that part of the problem for inexperienced black women writers is that they have no role models to whom they can relate. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that there are too few successful black writers. While black women admire writers such as Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, they feel that these writers are the exception and that they must have some “innate” capabilities far beyond what the average black woman could ever achieve. These prospective writers have no knowledge that writing, like any craft, can be learned if one is given adequate support and instruction. They seem to also lack the self-confidence to know that their experiences are worth preserving through the written word… this guide will show them how black women expressed themselves in this country, long before we were legally permitted to read or write” (Seen and Heard: A Non-Fiction Guide for Aspiring Black Women Writers, II: Box 1: Folder 15, Correspondence: Evelyn White (Author) and Faith Conlon (publisher) – 1991).

[3] Conlon, da Silva, and Wilson write in their introduction to The Things That Divide Us, “There are, of course, gaps in the anthology, serious ones. We received fewer stories from Latinas or Asian women, fewer from differently-abled or older women than we had hoped for. We extended our deadline twice, wrote more letters, made more phone calls, extended our deadline again. More stories arrived, though in smaller numbers than we could have wished” (Faith Conlon, Rachel da Silva, and Barbara Wilson, The Things That Divide Us: Stories by Women (Seattle: Seal Press, 1985), 11).

[4] Additionally, this anthology raised important issues of voice for both the editors and writers. In their introduction, Conlon, da Silva, and Wilson write, “Was it racist for a white author to speak through the character of a woman of color? What really constituted one’s class identity–childhood living situation or current circumstances? Were there too many stories from ‘those of dominant culture looking into other cultures,’ as one advisor worried?” Given the political trend of the second wave–and certainly of Seal Press–for feminist ideology to come from one’s own experience, questions of authenticity and legitimacy are bound to arise. The Combahee River Collective articulated this concept of authenticity in their 1977 statement clarifying their ideology as Black feminists, “Focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves” (Faith Conlon, Rachel da Silva, and Barbara Wilson, The Things That Divide Us, 8-10; Combahee River Collective, “The Combahee River Collective Statement” in Home Girls, A Black Feminist Anthology, edited by Barbara Smith (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Inc., 1983), 275).

[5] Faith Conlon, Rachel da Silva, and Barbara Wilson, The Things That Divide Us, 8.

[6] This letter is no exception to White’s humor. In Backbone 3, her biography at the end of the issue reads: “Evelyn C. White believes in The Wall Street Journal, Aretha Franklin and beer.” In another letter on 26 June 1985, White mentioned that she hoped to write a biography of Aretha Franklin, after being inspired by a Nina Simone concert.; File 27 Letter to Barbara Wilson. (Backbone 3: Essays, Interviews and Photographs by Northwest Women (Seattle: Seal Press, 1981), 89, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[7] Becky Birtha (b. 1948) is a poet and prose author, focusing on ideas of race, sexuality, and relationships. She published Lovers Choice (1987) and The Forbidden Poems (1991) with The Seal Press. Given this email, Evelyn White likely persuaded Birtha to publish with The Seal Press for the latter title.

[8] A woman who published more than once with Seal Press.

[9] Ntozake Shange (b. 1948) is an internationally renowned author, most known for For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf (Shameless Hussy Press, 1976). Shameless Hussy Press was a precursor to The Seal Press as the first feminist press founded in 1969 by Alta. She reflects, “I started the first feminist press in this wave of feminism in America. At that time, 94% of the books printed in the US were written by men. I called the press Shameless Hussy because my mother used that term for women she didn’t approve of, and no one approved of what I was doing.”

Evelyn C. White wrote Shange on 1 July 1985 to ask her to read White’s manuscript of Chain Chain Change, “provide comments which would be used, with your permission, for [the] jacket copy” (Alta, She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, web access, accessed 24 June 2016; Letter from Evelyn C. White to Ntozake Shange on 1 July 1985, Series II, Box 9, File 27, The Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[10] Betsy Brown (St. Martin’s Press, 1985).

[11] Unclear who she was specifically referring to.

[12] Gloria Naylor (b. 1950) writes about the lives of African American women, themes central to her debut novel, The Women of Brewster Place (The Viking Press, 1982).