“We are not superwomen”: Navigating Finances, Identity Politics, and Vision of a Feminist Press

Introduction to Documents 1 and 2: “Unbusinesslike” Conduct | Document 1 | Document 2

Introduction to Documents 3 and 4 | Document 3: Feminist Publishing Ethics | Document 4: Women in Print Publishing Accords

Document 5: Feminist Publishing Proposal From Ruth to Barbara

Introduction to Documents 6, 7, and 8: Seal Books | Document 6 | Document 7 | Document 8

Document 9: Women Who Dared | Document 10: “Cheat to Eat”

Introduction to Documents 11 and 12: Hate Mail | Document 11 | Document 12

Document 13: Outreach to Women of Color | Document 14: Letter to Angela Davis | Document 15: Letter from Audre Lorde | Document 16: “No More ‘Social Problems’ Projects”

Bibliography

Introduction to Documents 3 and 4

The following documents are both official statements released from the Third Annual Women in Print Conference. This conference occurred in the wake of one of the biggest scandals of the feminist print world: the sale of Lesbian Nuns to the June 1985 issue of Forum Magazine by the lesbian feminist print company Naiad.[1] Penthouse Forum, colloquially known as Forum Magazine was a softcore pornographic magazine (targeted towards men) featuring erotic literature and journalism.[2] It was created as a supplement to Penthouse Magazine. While Naiad had proper legal rights to sell the anthology, the contributing authors had no prior knowledge or consent. Many expressed hurt and frustration that their stories, which they had submitted as a feminist product to a feminist audience, were turned into mainstream pornography. This incident showcases a major example of a time that tradeoffs in the feminist print world between values and business were brought to public attention. Naiad Publisher Barbara Grier justified the decision to sell Lesbian Nuns on the principle that it would help the book reach a wider audience.[3] Yet clearly, Grier’s decision to sell Lesbian Nuns was first and foremost a business decision.

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective, most influential in the 1970s and early 1980s (primarily in North America and Western Europe). It differed from mainstream Second Wave feminism in its stance encouraging women to direct their energies toward other women rather than men, often advocating lesbianism as the logical result of feminism.[4] One of the founding documents of lesbian feminism, was “Woman-Identified Woman,” which explained the degradation of lesbians in society, the deviancy of their sexual practice under patriarchy, and the centrality of lesbians within the movement.[5]

Pornography and queerness were both contentious during the Second Wave, and Lesbian Nuns included both.[6] The annual Scholar and Feminist conference at Barnard College sparked national attention when its theme of “Sexuality” quickly became a platform for the debate between pornography and anti-pornography. The conference did not invite anti-pornography speakers or panelists, fearing their voice would dominate as it did in the national conversation. This sparked individuals such as Andrea Dworkin, radical feminist and famed anti-pornography activist, to picket the conference. The conference “created consternation, anger and uproar amongst American feminists and deepened the already scarring divisions in the American movement.”[7]

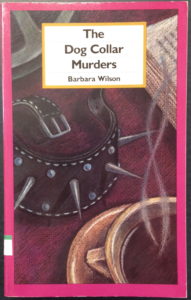

Barbara Wilson, co-founder and author for Seal Press, wrote The Dog Collar Murders, whose premise fictionalizes the debate at the Barnard conference. The first line of the book summary reads, “When Loie Marsh, prominent anti-pornography activist, is found strangled at a Seattle conference on women and sexuality, many fear that the polemical war between feminists has gone too far.” The entire novel is replete with political dialogue about the issue, for example, one character says, “As a lesbian video maker all my work is considered pornographic and subject to censorship.”[8] This line is particularly worth noting, given that lesbians against pornography censorship held a position different from heterosexual feminists advocating the same position, given that queer sexuality was considered deviant, criminal, and perverted at the time.

The following documents, the Statement of Publishing Ethics and Women in Print Accords, make efforts to emphasize the importance of morality and feminist ethics over business concerns. However, it is important to note the idealistic nature of both these documents. Neither document acknowledges the need of feminist print collectives to exist as businesses. Barbara Grier was quoted as saying that she thought much of the scandal surrounding the sale of Lesbian Nuns came from the fact that “It wasn’t cool to make money or even think about it. I think there was a lot of resentment of Naiad making this kind of choice.”[9] This phenomenon plays out in the documents.

Although these documents initially read as confident and self-assured declarations, they fail to fully explore the kinds of tensions over finances experienced by independent feminist print collectives that caused Naiad sell Lesbian Nuns to a platform that went against so many of their beliefs. It is especially interesting to compare these idealistic accords to the way Barbara Wilson and Seal Press treated Ginny NiCarthy (see Document 1). Evidently, these accords were harder to follow in practice than in theory.

[1] Lesbian Nuns is a best-selling feminist anthology of stories by nuns who had lesbian affairs in the convent or came out after leaving the convent.

[2] Faith Conlon to Paul Pintarich of Oregonian on 24 February 1995 affirming Seal Press’ commitment to publicly celebrating its queer literature. She writes, “When asked what Seal Press did not publish, my answer was: ‘We do not accept any racist, sexist, or homophobic work.’ (I was quoted as saying we do not publish homoerotic work!) Needless to say, this was an astounding error, given the fact that Seal Press publishes a great deal of lesbian literature. It was also a disturbing misquote in light of today’s political climate, in which conservative forces are attempting to silence the voices of lesbians and gay men” (Fax from Faith Conlon to Paul Pintarich, 24 February 1995, Series II, Box 1, File 26: Ruth Gundle Correspondence / Eighth Mountain Press, Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[3]Barbara Grier (1933-2011) was an American writer and publisher most widely known for co-founding Naiad Press. She is also referenced in another document from this collection, the Letter to Barbara Wilson from Ruth, as “Barbara G.”

[4] Although this sentiment was articulated by radical lesbians, other heterosexual feminists were less willing to include queerness in the larger agenda. Even if articulated on an interpersonal level, some excerpts from letters from Evelyn C. White, a Black lesbian, highlight some of this discomfort. When writing about a Sherley Williams’ submission to her anthology, Black Women’s Health Book: Speaking for Ourselves, “nice, but [the] line about ‘need mo’n jest some MAN (emphasis mine) to set me right’–raises heterosexist hackles. Am sure lesbian contributors to the book will bitch about that.” Williams’ poem is neither in the 1990 nor the 1994 edition of the anthology; perhaps the content was too contentious.

Another letter comes after the publication of Black Women’s Health Book, “I called Sheila Battle about the request to reprint her article [“Moving Targets: Alcohol, Crack, and Black Women”]. She seemed kind of hesitant about it I don’t know why. She said she would think about it and get back to me. She hasn’t as of yet. Doesn’t the Seal Press have the ultimate right to grant reprint permission, anyway? … I’ve been wondering if there aren’t a few homophobic vibes coming out of Sheila. She’s been kind of strange ever since all the publicity about the book broke–much of which was in the gay press. Oh well” (Letter from Evelyn C. White to Faith Conlon, 23 August 1989, Series II, Box 1, File 33, Correspondence: Evelyn White (1986-1989), The Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections; Letter from Evelyn C. White to Faith Conlon, 3 February 1991, Series II, Box 1, File 33, Correspondence: Evelyn White (1986-1989), The Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[5] Radicalesbians, “Woman-Identified Woman,” 1970, web access, accessed 5 July 2016.

[6] Pornography was a contentious between Second Wave feminists. In a letter from Faith Conlon to Deb Brown on 16 September 1988, Conlon suggests images for the cover of The Dog Collar Murders which Brown will design. “I think you might want to play on the ideas of the porn/sex debates, that is, so people don’t think the book is about dead puppies. Though some crucial scenes take place on the houseboat, which would make a nice setting, but maybe not provocative enough. You could work with just a few of the elements — the dog collar (murder weapon), s/m paraphernalia, etc. Harder to work in an element that would symbolize the anti-porn side (both religious rightwing and the Dworkin camp). I think something pretty simple but graphic might be best.” Interestingly, those at Seal Press framed the debate as “pro-sex versus anti-porn” as opposed to others nationally who saw the issue as one of censorship or freedom of the press. The remnants of articulating sex-positivity within the feminist movement are still seen today.

The Dog Collar Murders description reads:

“When Loie Marsh, prominent anti-pornography activist, is found strangled at a Seattle conference on women and sexuality, many fear that the polemical war between feminists has gone too far. But the clues point to more complicated motives and only Pam Nilsen, the sleuth of Murder in the Collective and Sisters of the Road, can determine what they are. Who wanted Loie dead? Could it be the feminists opposed to censorship or the local lesbian sadomasochists? Loie’s ex-lover and research collaborator? Or was there something in Loie’s past that still haunted her?

“As She searches for answers, Pam talks to people from all sides of the pornography issue, from Christian fundamentalists to ‘sexual dissidents,’ and comes to terms with her own fears and desires. Meanwhile the murderer is still at large and strikes again, putting even Pam in danger.”

Additionally, another line which highlights one argument given reads, “I see the reduction of the complexity of looking to the casual anti-porn theory that ‘porn leads to violence and so it equals violence against women’ as simplistic and ultimately harmful” (Series II, Box 1, File 13, Deb Brown Correspondence, The Seal Press, Oberlin College Special Collections; Barbara Wilson, The Dog Collar Murders (Seattle: Seal Press, 1989), 113, Oberlin College Special Collections).

[7] Elizabeth Wilson, “‘Between Pleasure and Danger’: The Barnard Conference on Sexuality,” in Feminist Review, No. 13 (Spring, 1983), 35.

[8] Barbara Wilson, The Dog Collar Murders, 26.

[9] John L. Dececco, Before Stonewall (New York: Harrington Park Press, 2002), 261.