Document 6:

Author: James Harris Fairchild

Recipient: Mary Fletcher Kellogg

Date: unknown, Late April or Early May 1838

Location: Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence,

1771-1926, RG 2/003.

Document Type: Transcript (1939) Autograph Letter, Signed by Author.

Introduction:

Though Mary’s last letter to James spoke of the need for patience, in this letter, James once again reveals his impatience. Here, James professes his love to Mary. He writes that he would begin “without the formality of a prologue” yet it still takes him quite some time to muster up the courage to actually write what he is feeling. This nervousness clearly indicates that though James fulfilled his expected role as the romantic aggressor, he would have preferred it had Mary made at least a few overtures of her own. He writes that he had hoped Mary would have disclosed her feelings for him earlier and is worried that she misunderstood the nature of their correspondence, even suggesting that she might have been toying with him.

Also of note is where James writes at the end “You see with what freedom I have written, I shall expect the same in return.” However, he did not realize that Mary, as a woman, did not have the liberty to write such professions of her own love. It was her duty as a woman to restrain both his and her own feelings. Additionally, though he acknowledges the possibility that Mary might have felt nothing for him, he seems entirely blind to the possibility that she could care for him, but not feel the passionate love for him that he does for her. This blindness to both Mary’s position as a woman and the possibility that her feelings might not always match his own exactly, is a recurring theme in their courtship correspondence, particularly in their earliest letters.

Transcription:

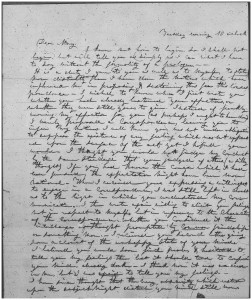

Tuesday Evening 10 o’clock. <Late Apr. or early May 1838>

Dear Mary<,>

I know not how to begin, so I shall not begin, but will tell you as simply as I can what I have to say without the formality of a prologue.

It is a duty I owe to you as well as to myself, to state more distinctly than I have done the motive which has in<f>luenced me in proposing and sustaining thus far this correspondence. I wished to know, when I first wrote you, whether you had already bestowed your affections or whether they were still yours to give. Instead of frankly avowing my affection for you (as perhaps I ought to have done) I merely proposed a correspondence, leaving you to infer the motives. I well know you were not under obligation to suppose the existence of any feeling which was not expressed upon the surface of the act, yet I hoped you would. I thought you would not judge my conduct by the same standard that you judged of others<,> (a silly thought). If you had known the course which I had ever pursued, the expectation might have been more rational. When I received yours expressing a willingness to engage in a correspondence<,> I was still left in doubt as to the light in which you understood my communication. Then I wrote again wishing to elicit your feelings<,> not in respect to myself, but in reference to the character of the correspondence, whether you considered it the interchange of thought prompted by common friendship or something more. I received your second letter, giving some account of the unhappy state of your mind.1 I believed you would soon find peace and hesitated to tell you my feelings then, lest it should tend to confuse your mind, already dark. I think now it was an error in me, but I was afraid to tell you my feelings. I have since thought that the very obscurity which rested upon the subject might disturb your mind still more.

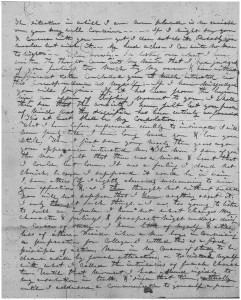

The situation in which I am now placed is no enviable one, you may well conceive —- <i>f I might see you and converse with you — yet I dare not do it. Probably you would not wish it. My head aches. I can write not more tonight.

Wednesday morning.

In looking over what I have written, the thought came into my mind that I had judged of your feelings too much by my own and have without sufficient data concluded you as much interested in this correspondence as myself. If I have misjudged you will forgive, if it has been from the beginning an affair of trifling moment to you, I shall then see that the anxiety I have felt lest your peace of mind was the sacrifice, has been entirely unfounded. This at least shall be my consolation.

What I have before endeavored darkly to insinuate, I will now freely tell. I have long loved you and love you still. When I first saw you, nearly three years ago, your appearance interested me. The more I saw of you, the more I felt that there was a mind and heart that I could but love. It was a feeling I dared not cherish because I supposed it would be in vain. <I> saw others (if I rightly observed) endeavoring to win your affections and, as I then thought, not without success. You will not suppose that I knew anything about it. I only thought such things. I was too young to listen to such an impulse. I knew not what changes my character and feelings and prospects might undergo during a course of study. I knew little of myself and still less of others. Besides, when a mere boy, in commencing a preparation for college, I settled this as a fixed principle of action, <n>ever in my course of study to be drawn aside by female attractions or to disturb myself with what I called the intricacies of female character. Until that moment I had adhered rigidly to that resolution in truth, and since that time externally until I addressed a communication to yourself a few weeks since. As I said before, I have hesitated to make this avowal on account of your state of mind, and then I have feared not to make it. For you to maintain such a correspondence without any ostensible end or aim<,> I knew must at least be unpleasant. I know too that a state of spiritual darkness is not favorable to the decision of a question upon which one’s happiness and future usefulness may depend. I have felt that darkness in my own mind and you have told me that it existed in yours.

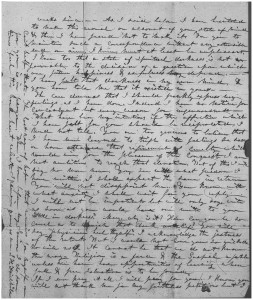

The case demands that I should frankly express my feelings as I have done. Indeed I have no motive for concealment but every reason for ingenuousness. What have been intentions if the affection which I have felt for you should be reciprocated<,> I need not tell. You are too generous to believe that I have ever learned to trifle with feelings so sacred or have attained that refinement of cruelty which would win for the pleasure of the conquest. I am not ambitious to reach that elevation. But of this I will say no more now. You see with what freedom I have written, I shall expect the same in return. You will not disappoint me. You know with what anxiety I shall wait for your reply. I will not be impatient but only say, write as soon as you would have one write to you……. [sic]

If I ever pray at all I will pray for you. I know you will not thank me for my faithless petitions, but I can’t help that. The last ray of hope that remains for myself or for you is in prayer. When I bow before my Savior, I do sometimes feel this hard heart relent.

I remain yours as ever<,>

J. H. FAIRCHILD

Transcribed by Eve Kummer-Landau.

1Here, James was referring to a letter Mary sent him where she voiced concerns that she would never be a true Christian.