Document 13

Author: James Harris Fairchild

Recipient: Mary Fletcher Kellogg

Date: 22 November 1840

Location: Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence,

1771-1926, RG 2/003.

Document Type: Transcript (1939) Autograph Letter, Signed by Author.

Introduction:

The following letter is one of James’ letters to Mary, over two and a half years into their correspondence. At this time, James was preaching in Palmyra, Michigan, over his winter break, while Mary was living with her family in Minden, Louisiana, where they had moved in the summer of 1839. Apart from a brief visit in Cincinnati before Mary left for Louisiana, it had been over two years since the couple had spoken in person, and the stress of trying to maintain their relationship merely through writing shows in these next few letters. Their relationship was further complicated by the fact that they were a thousand miles apart. Mail traveled slowly and it was often delayed, meaning that one letter might take months to reach its destination. As the following letters show, this delay made misinterpretations easy and prevented quick corrections, causing prolonged stress. In this letter, James reveals his worry over a letter that Mary had sent him where she seemed concerned about the future of their relationship. In one of James’ earlier letters, he had mentioned a sermon given by Professor Finney on the subject of the requirements for a pastor’s wife and the dangers of long engagements. Though James did not appear to have found those remarks pointed, Mary assumed they were, and in her letter of 5 October, she vaguely seemed to indicate that it would be possible to break off the engagement if James found her unsuitable. In the letter below, James does his best to answer her fears and reaffirm his love for her, but the tensions between them, due to bothMary’s continued belief that she might not be suitable for the role of a pastor’s wife, as well as the strain of their long separation, are clearly evident.

Transcription:

Palmyra, Lenawee Co., Michigan,

Sabbath Eve., November 22, 1840.

My own loved girl,

It is the <S>abbath, but it will not be wrong for me to write a little to you. It is a day sacred to me, not only because it is the <S>abbath, but because it is your own birthday. How can I better spend its hallowed close than in giving here a token that I have remembered it and have remembered you. Forgive me, I did not mean to imply that such a token is necessary, but let it pass.

I have another proof that it is not wrong for me to write you today which you will find, mutatis mutandis1, in Matthew 5:23 and 242. (Pardon my sermon<iz>ing style, I am a preacher now.)

My dear Mary, I received your letter of October 5th on Friday. I spread it on the table before me and sat two hours with my head in my hand, gazing at its mysterious lines. It did not take so long to read it, for the letter was not long. The first hour and a half<,> I felt nothing but a mingled emotion of sorrow and surprise. The last half hour<,> I gathered courage and looked at the subject like a philosopher. . . . . [sic] Then I put memory, consciousness<,> and conscience to the <r>ack to ascertain what unkind word I had written in that letter of August 25th, but they obstinately refused to testify. Yet there must have been something. If there is an expression in it that was not dictated by the deepest love and confidence and satisfaction, then the language most shamefully misrepresented my heart, for my wildest dream of you in the darkest hour of midnight has never been anything else than confidence and love and satisfaction. . . .[sic] But there must be something in that letter of mine<,> dated August 25th<,> that would explain it. You speak<,> now and then<,> covertly<,> about “regret, remedy”, etc. Who feels the regret? Who needs the remedy? They are strange words to me. No, Mary, let me say now and forever that I have had no feeling on the subject that was not entirely opposed to regret<,> and never since our engagement have I had any other feeling than entire and perfect satisfaction. I have received no “remonstrance from Professor Finney3 nor from any of my fellow students,” and<,> if I had, I should only have thanked them for their good intention and told them to reserve their kindness for those that stand in greater need. I have never conversed with Professor Finney about it, nor did I regard any of his remarks as intended for me, personally. Indeed, he said nothing that would have disturbed me in the least if I supposed he intended it for me. From my fellow students, I have never received anything but congratulations. My friends too, my father’s family, have ever manifested the utmost satisfaction. But all that is of no consequence. I am satisfied.

Perhaps, Mary, you have thought I manifested too much anxiety to have you return to Oberlin to pursue your studies. I can see that this might be misinterpreted. Whenever you have hinted to me that you might not “be qualified for the station you would be expected to fill,”4 I have always endeavored to set your mind at rest. You know me too well, Mary, to suspect me of flattery<,> and I have known you too well ever to doubt that you would be fitted for the highest station to which I could hope to introduce you, were I ever so ambitious<,> and<,> since ambitions has constitu<t>ed no part of my plan, you cannot doubt that I have ever been content in the affection and confidence of my own sincere and simple-hearted Mary….[sic]

But you will not distrust me, I know you will not, and I “will give you credit for” a thousand times “more affection and sympathy than are expressed in that letter,” and so the matter is all settled.5

Now I must tell you where I am, something about myself. I have been here in Michigan a little more than two weeks as I left Oberlin a day or two after I wrote to you last. At home I witnessed Catharine’s marriage. The wedding was done up in country style. All the cousins of the third and fourth generation were there to the number of 50 or 60. Poor girl, she <l>ooked rather pale and slender7 by the side of her tall and robust farmer bridegroom. But she loves him and he loves her<,> and I doubt not they will be very happy.

Next morning<,> I came away and arrived here Saturday night after some delays but no accidents<,> except running off the railroad between Toldeo8 and this place….. [sic]

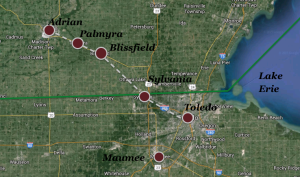

This Palmyra9 is a small village situated on the river Raisin where the Toledo and Adrianrailroad crosses it, about 27 miles from Toledo and 5 or 6 from Adrian.10 There are perhaps 5 or 6 hundred inhabitants in the village, very intelligent people, mostly from New York. The church is small, numbering about 45 members, and here I am a preacher with all the responsibilities of a pastor upon me.

This is the third birthday of yours that has passed since we were engaged<,> and we have not spent one of them together. Two years ago, you were on the Ohio and I was in New York.11 One year ago, you were in Louisiana and I in Oberlin. Now you are in Louisiana and I in Michigan. Heaven grant that next year we may not be so far asunder. Oh, I would be glad if you could get this letter tonight and I could have yours tomorrow, but goodnight.

MONDAY MORNING. [sic]

Mary, in one part of your short letter you say it would seem to be a sacrifice of my interest, as separate from yours, to go South this fall. Mary<,> I have no interest separate from yours. <If> I have thought of the future with any anticipation or hope of happiness, your own presence has constituted the foreground of the picture. If I have breathed a prayer to heaven for present or future good, that prayer has always included you. But I have said enough.

My situation here is very pleasan<t,> and<,> if I can be the means of doing a little good, I shall be happy. I live in the family of one Dr. Dearborn,12 a quiet little family- have two spacious rooms here<,> all to myself <,> so that I can be as secluded as I please. But I hope to become more acquainted with the world tha<n> I am now and learn the means of influencing the minds and breasts of others.

Brothers Foster13 and Fisher14 came on with me to Michigan and are both located on the railroad between this place and Toledo. Foster is at Sylvania,15 about 17 miles from me<,> and Fisher at Blissfield,16 5 miles distant, so that we can see each other any day in 10 or 15 minutes if the notion takes us. Foster is preaching<,> and Fisher talks on the <S>abbath and teaches singing school. Perhaps he will have a school in this <v>illage too. He will be here tomorrow….. [sic]

Next Wednesday, you recollect, will be my birthday- 23 years old. I wonder if my mother is not mistaken. Thursday is our “<T>hanksgiving day<,>”17 and I must put on a thanksgiving sermon. It will not be much of a talk, will it? I suppose you have no such days south… [sic]

I wish I had a folio sheet,18 but this must suffice. Love to all.

Ever your own,

James

Transcribed by Joanna Wiley and Rebecca Debus.

[1] mutatis mutandis “with the necessary changes having been made”

[2] 23 “Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, 24 leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to them; then come and offer your gift.

[3] Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875). Finney was a revivalist preacher and one of the most important figures from the Second Great Awakening. In 1835, he became a Professor and the head of the Theological Department at Oberlin, and in 1851, Finney became the second President of Oberlin College (Oberlin College Archives, “Charles Grandison Finney Presidential Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 11 August 2015).

[4] This is a recurring concern of Mary’s, and appears in several letters.

[5] Here, James is quoting from Mary’s 5 October 1840 letter, where she wrote: “You will forgive this hastily written sheet and still give me credit for sympathy and affection toward yourself, which are not expressed here.”

[6] Catharine (or Catherine) Baxter Fairchild (1820-1905), James’ oldest sister, who married Chester A. Cooley (1812-1896). She attended the Oberlin College Preparatory Department from 1834 to 1835, and was enrolled in the Ladies’ Course (later called the Literary Course) from 1837 to 1838. She and her husband lived in Ohio (General Catalogue of Oberlin College 1833-1908. Cleveland, Ohio: The O. S. Hubbell Printing CO., 1909;LindaB. “Catherine B Cooley (1820 – 1905) – Find A Grave Memorial.” Find A Grave. web address, accessed 11 August 11 2015).

[7] According to James’ other letters to Mary, it seems that Catharine had been fighting off a serious illness just before her marriage, which might have accounted for her wan appearance.

[8] Toledo, Ohio, was a fairly new city, having been formed in 1833 by two towns who were attempting to have the terminus of the Erie Canal put at their city. Though the canal did not directly end in Toledo, it did provide a great economic boost to the city, and when James would have been there, it was growing into a thriving metropolis.

[9] Palmyra, Michigan, which was founded in 1834 (“Palmyra Township History,” Palmyra Township, web address, accessed 11 August 2015).

[10] Adrian, Michigan, was founded in 1828, and became the terminus for the Erie & Kalamazoo Railroad, which ran north-west from Toledo (History of Lenawee County, Michigan – Chapter 3, Settlement and Organization. The Western Historical Society, 1909, web address, accessed 11 August 2015).

[11] James spent his 1838-1839 winter vacation in Ripley, New York, where he had been invited to teach school (Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926,RG 2/003).

[12] This is most likely Jesse A. Dearborn (1807-1848), who apparently lived with his wife and three children (“1840 United States Federal Census – AncestryLibrary.com,” Ancestry.com, web address, accessed 11 August 2015; Sincerely Unknown. “J A Dearborn ( – 1848) – Find A Grave Memorial,” Find A Grave, web address, accessed August 11, 2015).

[13] Cephas Foster (1808-1885) was from Palmyra, Michigan. He was a member of James’ class at Oberlin, graduating from the College with an A.B. in 1838, and from the Theological Seminary in 1841. After his graduation from the Seminary, he married Sophia Cummings (d. 1893), who had attended Oberlin from 1833 to 1834, and was a student in the Ladies’ Course from 1840 to 1841. Cephas Foster then preached for a year in Oberlin before moving to McConnelsville, Ohio, where he farmed for three years. He then taught at a Ladies’ Seminary in Rockford, Illinois, from 1846 to 1848, as a member of a publishing firm in Galena, Illinois, from 1848 to 1858, and then owned an insurance business (Former Student File: Cephas Foster. Record Group 28/2, Box 341. Oberlin College Archives).

[14] Caleb Ellis Fisher (1815-1876). He graduated from Oberlin College in 1841 with an A.B. and then from the Theological Seminary in 1844. He married Mary Hosford, Mary Kellogg’s classmate, one of the first three women to earn an A.B. in the United States. They had three children together, all of whom attended Oberlin College. Caleb Fisher made a career preaching, and also served as Oberlin College’s financial agent from 1873 to 1875 (Former Student File: Caleb Ellis Fisher. Record Group 28/2, Box 328. Oberlin College Archives).

[15] Sylvania, Ohio.

[16] Blissfield, Michigan.

[17] At this time, Thanksgiving was not a national holiday, nor did it have a fixed date, though most people celebrated it sometime in late November.

[18] A folio sheet is larger than a regular one, and made so it can be folded to form pages of a book.