“You will see with what freedom I have written”: The Courtship Correspondence of James H. Fairchild and Mary F. Kellogg

Project Group: Eve Kummer-Landau, Kasey Ulery, Joanna Wiley

Student Editor: Rebecca Debus

Introduction:

This project focuses on the courtship correspondence between James Harris Fairchild (1817-1902), later the third president of Oberlin College, and Mary Fletcher Kellogg (1819- 1890), who married him. In 1837, James sent a letter to Mary requesting that they begin a correspondence.1 Though initially Mary appeared hesitant, James persisted, and their correspondence soon led to an engagement. They married in 1841 and remained happily together until Mary’s death in 1890.2 The letters included in this project offer glimpses into early life at Oberlin, antebellum courtship practices, and the racial attitudes of anti-slavery Oberlinians. They also offer much insight into the life of one of Oberlin’s presidents and his loving wife.

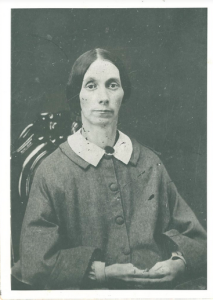

Mary Fletcher Kellogg was the oldest daughter of businessman Titus Kellogg and his wife Lucy Fletcher Kellogg.3 Mary was raised in the city of Jamestown in upstate New York, where she received her early education. At age fifteen, Mary convinced her family to allow her to continue her education at Oberlin College, which was, as she argued, the only place in the country where a woman could study Greek.4 Along with her oldest brother, Charles Augustus, she enrolled in Oberlin College in 1835.5 In the early nineteenth century, higher education for women was extremely limited. Oberlin was the first American college offering advanced classes to women, and decided in 1837 to allow women to pursue the Bachelor of Arts degree. In that year, Mary Kellogg along with three other women (all of whom had previously been members of the Preparatory Department or the Ladies’ Course) became the first women in the United States to enroll in a degree-granting program. Although Mary Kellogg did not complete her education, in 1841, her fellow classmates became the first women in the United States to earn an A.B.6

James Harris Fairchild was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the third son of Grandison Fairchild7 and his wife Nancy Harris Fairchild. In 1818, his family moved west to Brownhelm, Ohio, approximately ten miles from where Oberlin College would later be founded. James and his older brother Henry moved to Elyria to attend school in 1832. In 1834 the two entered Oberlin College as members of its first freshman class.8 James graduated from Oberlin College in 1838, and along with the rest of his class, which now numbered about twenty men, he entered the Oberlin Theological Seminary. While he was attending the Seminary he also served as a tutor in the College, and on his winter breaks worked as both a teacher and a preacher.9 Upon his graduation from the Seminary, James was ordained by the Lorain County Congregational Association, but instead of preaching, began teaching Hebrew at Oberlin College. In the fall of 1841, he officially took on the position of Professor of Languages at Oberlin, and held various professorships at Oberlin for the rest of his working life.10 During his time at Oberlin, although he was not one of the town’s most outspoken abolitionists, he also engaged in abolitionist activities such as the Oberlin-Wellington rescue. In 1866, Fairchild became the third president of Oberlin College. He remained President until he resigned from the post in 1889.11 He retained his professorship for another nine years, and remained a member of the College’s Board of Trustees until his death from heart failure in 1902.12

Source: Bradford, Thomas G. “United States. – David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.” David

Rumsey Map Collection. web address, accessed August 7, 2015.

James Fairchild and Mary Kellogg met during their time in Oberlin. According to James’ memoir, he initially met Mary while serving as a tutor for one of her college classes, but was so shy about instructing a woman that they did not really become acquainted until they later took an algebra class together.13 In 1838, mere months after James had initiated their romantic correspondence, Mary had to return home, as her family had suffered from severe financial problems and was planning to move to the South for a fresh start.14 Despite their very short courtship, Mary and James became engaged the night before she left Oberlin, and maintained their correspondence over three years of separation. After James graduated from the Theological Seminary in 1841, he traveled to Minden, Louisiana, where Mary’s family had settled. On 29 November 1841, Mary Fletcher and James Fairchild were married in Minden.15 They then returned to Oberlin, where they remained for the rest of their lives.

During the Fairchilds’ time, Oberlin College was a radical place that offered opportunities not found anywhere else. In addition to coeducation, Oberlin also opened its doors to African American students, and was a center of abolitionism. Oberlin’s general religious beliefs were considered radical (and, in some cases, even heretical) but also allowed for a great deal of free thought and discussion. Though this radicalism allowed women and people of color increased access to higher education, it also invited a great deal of scrutiny and criticism from the rest of the country. Other religious groups were highly suspicious of Oberlin’s theological teachings, and sometimes refused to ordain those educated there.16 More severely, Oberlin’s abolitionist beliefs actually put the students and school in danger. On James’ trip through the South in 1841, he was forced to conceal the fact that he was from Oberlin, or he risked physical harm from Southerners who deeply resented Oberlin’s concerted efforts to promote abolition, educate people of color, and aid escaped slaves.17 Oberlin’s experiment in coeducation also drew the ire of many, who felt it would lead to licentious behavior. This meant that Oberlin College was forced to adopt a rigid code of behavior for male and female interactions, and any infraction had the potential to prompt national outrage. In the letters of Mary Kellogg and James Fairchild, it is possible to see what effect both Oberlin’s opportunities and oft-maligned radicalism had on its students, particularly those who were far more moderate in their personal beliefs.

These letters also offer a compelling picture of women’s and men’s roles in antebellum courtship. Although men were allowed, even expected, to be passionate and push the boundaries of what was considered acceptable or appropriate, women were forced to be far more restrained in their behavior. In the medieval world, women were seen as highly sexual beings, but in the early modern period (in America, specifically after the Revolutionary War ended) women were seen as having little sexual desire, and men became viewed as the sexual aggressors.18 It was during this time that a woman’s virtue became explicitly tied with her sexual behavior, or rather lack thereof. Though this notion of women as generally sexless beings did provide a reason for women to refuse sexual advances, it also meant that women were now held responsible for men’s behavior. Therefore, women’s ability to be passionate or bluntly speak their own minds in matters of romance was limited due to the need for them to present a respectable and virtuous image so that they could not be blamed for unwanted advances.19 These courtship letters clearly reflect both James’ ability to speak with perfect freedom and Mary’s need to be restrained.

The mid-nineteenth century was also a time when the roles of women in general were shifting. Questions of women’s education, women’s place in society, and women’s legal and political rights were moving into national importance. Though both Mary and James clearly supported women’s education, their letters reveal that both of them were not nearly as supportive of other moves for women’s rights. This tension between their relatively egalitarian beliefs in some areas and their more conservative views in others offers a glimpse into just how complex, and often confusing, these changing social dynamics were for people at the time.

Mary Kellogg and James Fairchild’s letters beautifully document antebellum American life, courtship practices, and the formative years of Oberlin College. Their writing is especially valuable to us today for their personal connections to pioneering institutions and activities, but it is also valuable for the tremendous insight it gives into the thoughts and feelings of those who lived so long ago.

Note: The documents in this edition are all based on typed transcriptions, compiled into three bound volumes, of James Fairchild’s and Mary Kellogg’s original handwritten courtship letters. These transcriptions were made in 1939 by the Fairchilds’ son, James Thome Fairchild, and their granddaughter, Dorothy Kellogg Fairchild Graham. The transcriptions include explanatory footnotes added by Graham and Fairchild to give context to the letters; these footnotes have been included in the transcriptions provided in this collection, and are indicated with asterisks. The typed transcriptions created by Graham and Fairchild also include corrections and additions written in pen. These additions have been indicated by placing them between arrows <like so.>

1Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003.

2Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

3Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015; Oberlin College Archives, “Lucy Fletcher Kellogg Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 11 August 2015.

4Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Former Student File: President James Harris Fairchild. Record Group 28/2, Box 312. Oberlin College Archives

5Former Student File: Mary Fletcher Kellogg (Mrs. James H. Fairchild). Record Group 28/3, Box 79. Oberlin College Archives.

6Former Student File: Mary Fletcher Kellogg (Mrs. James H. Fairchild). Record Group 28/3, Box 79. Oberlin College Archives.

7Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

8Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

9Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

10Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003; Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

11 Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

12 Oberlin College Archives, “James H. Fairchild Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 31 July 2015.

13Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003.

14Oberlin College Archives, “Lucy Fletcher Kellogg Papers Finding Guide.” web address, accessed 11 August 2015; Reports of Cases Adjudged and Determined in the Supreme Court of Judicature and Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors of the State of New York. Lawyer’s co-operative publishing Company, 1884.

15Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003.

16Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003.

17Oberlin College Archives, James H. Fairchild Papers. Series III Courtship Correspondence, 1771-1926, RG 2/003.

18Carol Lasser and Stacey M. Robertson. Antebellum Women: Private, Public, Partisan. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010

19 Lasser and Robertson, Antebellum Women: Private, Public, Partisan. 9.