Document 3

Author: Sarah Furnas Wells

Title: Ten Years’ Travel Around the World. or From Land to Land, Isle to Isle, and Sea to Sea (pages 396-402).

Date: 1885

Source: Special Collections, Oberlin College Archives

Document Type: Printed Document (West Milton, OH: Morning Star Publishing Company)

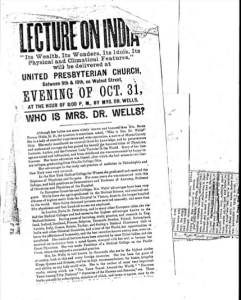

This is another excerpt from Wells’ book, specifically taken from one of the chapters detailing her visit to India. Her view of other religions was tinged with prevailing Western attitudes of the day; she clearly shared the evangelical viewpoint of many nineteenth-century Oberlin alumnae. Much of the book is devoted to condemning “heathen” religious practices. Wells’ other book, Mysteries of the Harems and Zenanas or Life of Oriental Women, warrants mention here1. As a woman doctor, she had special access to women’s quarters where men were not permitted. Her goal in writing Mysteries was “the liberation and evangelization of woman.” Coming from a religious household, Wells, like woman missionaries at the time, saw female agency and Christianization as inextricably linked2. Wells claimed that Islamic and Hindu customs were misogynistic, and that everything she wrote was true, but she might have been biased due to the cultural landscape from which she came3.

An anecdote not in this extract tells of a baby nearly “sacrificed” by drowning by its mother, only to be rescued by British soldiers. This sounds like a fabrication steeped in imperialist bias, but in fact, female infanticide among Indian families was a practice continuing as late as the 1980s, although the British formally banned it in 1870. According to a study by Elisabeth Bumiller, “[A] chief reason for the murders was the exorbitant cost of dowries among the upper castes4.” Cultural tradition devalued daughters significantly. Regarding the arranged marriage of prepubescent girls mentioned in the text below, Indian communities did practice it. Indian and English intellectuals alike found this perturbing and debated raising the age of consent5. Wells, meanwhile, seemed to want to empower the women she met through medical education and literacy. Although Wells’ culture ascribed inferiority to other cultures, her apprehensions about international women’s situations were not without basis in reality. Moreover, she and her contemporaries also opposed the restrictions Western customs placed on women.

A VISIT TO THE ZENANAS.

While at Delhi, I often visited the zenanas and gave medical treatment and advice to the women. At 5. A. M. the carriage was regularly sent by the lady superintendent of the English Mission to take me to those places. We went at this early hour to avoid the heat of the day. The name “zenana,” [sic] is derived from the Persian word for woman, and is applied to that part of the home of an Indian gentleman reserved especially for the women, where no unbidden guests ever dare to enter. We always found the women glad to see us, ready in their recitations, and eager to have medical treatment, from the fact that they are never visited by medical men. A woman would rather die than be seen by another man than her husband; and even in case of sickness and death no other man is permitted to be present. If the husband consents to call a male physician to prescribe for some favorite wife who is afflicted, she must be veiled or stand behind a curtain and only allow her hands to pass from behind it, in order that her pulse may be examined; and in case he desires to see her tongue, a slit is made in the sheet, through which she puts it to his view.

In the zenanas we find a vast sea of human life apart from the rest of the world–a terra incognita. No grander field for female physicians can be found than in the zenanas. Those who go out as teachers and missionaries will find a knowledge of medicine as an invaluable aid. I was welcomed to the harems and zenanas throughout all my residence in Oriental lands. At Constantinople, in Palestine, in Egypt, India and Java, I was often seated among groups of women, eager and attentive to gather any information that might be given. We had classes of native women that took great interest in such sanitary and medical subjects as they were taught according to their capacity of acquirement. Some of them made good assistants in the dispensary6 department.

Among the incidents of my zenana acquaintance, was a visit to the family of a Nabob (Muslim prince). As we drew near the palace, my friend said, “We will leave the carriage now.” On getting out, we found the narrow streets obstructed by ox carts, buffalo cows, sheep, servants, and dogs, all adding to the chatter and confusion. We reached the outer door, where a chained monkey made a vicious bound towards us as we passed. Going through a dark low passage which made frequent turns, with guards stationed at near intervals and servants passing to and fro, we at last entered a large and splendid court. In the meantime my friend explained that the ladies live all apart from their husbands, and that the entrance had been made as obscure as possible that they might not be annoyed by intruders.

A large lady came to us with a child in her arms, and was introduced as the Begum (princess) of the palace. We took our seats upon the divan in the veranda, where we were joined by her daughter. They spoke of being in white, which is worn for mourning by Moslem [sic] women. They said that they had lost a relative. Yet this did not fully account to my mind for the settled expression of sadness in the countenance of the younger lady.

[…]

One afternoon, the gentleman came to the hotel and called for my husband. After they had been in private conversation for about two hours, I was informed that the object of his visit was to invite me to go to his palace and prescribe for the women of the zenana. Being accustomed to respond promptly to professional calls at home, I replied, “I shall be ready in about twenty minutes.” But I was told that I was not to go that day, and that when they were ready there would be a carriage and attendants set for me. It being our custom to include carriage, coachman, and bearer when we engaged board, I replied that we had our own conveyance. I was then made to understand that they desired to pay me that compliment. Two days later the carriage was sent. On reaching the dwelling, the bearer received us at the street door, and conducted us to the top of the stair-way where stood the princely

merchant, the owner of the house and the head of a numerous family. He gave us a polite welcome, and passing through a marble-laid hall, we took our seats in the drawing room, furnished in a luxurious style. A servant was called and approached me with the usual graceful salaam, and stepping back a little, engaged in fanning me with a great fan about a yard in diameter. Covered with linen, and having a deep ruffle attached to the circumference, it was fastened to a staff and thus could easily be revolved. After different delicious, but unintoxicating drinks and coffee had been served, my husband was invited to remain in company with others, while I was conducted into the zenana, in which I found fifty women seated upon the matted floor. The merchant acted as interpreter, the first wife only being permitted to speak to me, except in answer to questions concerning the state of their health. I found on questioning them that they did not leave the house except once a year, and then only to perform some religions [sic] ceremony at the river. Also some of them had been on a pilgrimage to a highly venerated shrine, or temple. They were the wives of two brothers; their ages ranged from eleven to forty-five years. On inquiring if they understood music, or could read or sew, this man of great wealth gave a negative answer, with the remark, “They have no time.” This prompted the inquiry, “How do they spend their time?” “You see the floors all wet,” he said; “they have had to wash them because you came, and when you go away they must wash them again, for they are made unclean by the presence of any one who is not of their faith. They must also themselves perform ablutions before the sun goes down.” He continued, “In the morning they rise, worship the household gods, then get breakfast, and afterwards the children must be cared for, and then it is time to get dinner. After dinner is over and the house-work done, it is time to get supper; and the performance of the evening worship ends the day.”

He called attention to a niece of about eight years, who had just been married, remarking, “we do not allow our women to marry young; we do not believe in early marriages.” Although many of them had long been afflicted with distressing maladies, a doctor had been called only in one instance. Then an English surgeon had operated upon one of them for cancer of the neck.

I made visits to other zenanas, and was invited to see some of the female relations of the late king of Delhi. In one of the Moslem zenanas I found two women, nearly twenty years of age, who were able to read in different languages, but had never been outside of the walls of their own home, except in a few instances, and then only in a closed carriage.

Transcribed by Joanna Wiley

1 Harems, living quarters for the women in a Muslim household, were a subject of much Orientalist fetishization by Europeans in the nineteenth century, as Islamic societies practiced polygyny.

2 For a detailed picture of an Oberlin missionary woman in Asia, see “Women ‘Rule the World’: The Lives and Impact of Female Missionaries,” also on this website.

3“A strategy which was followed by nearly all imperial powers in the nineteenth century was the denigration of politically and economically subjugated cultures by foregrounding the position of women in these societies, compared with the more obvious freedoms of the European woman” (Janaki Nair, Women and Law in Colonial India (Kali for Women, New Delhi, 1996,) 51).

4 Elisabeth Bumiller, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons (New York: Random House, 1990,) 104.

5 Nair, Women and Law in Colonial India, 71.

6A dispensary was a pharmacy or clinic. Many American women set up dispensaries of their own throughout the United States in the later nineteenth century.