Document 2

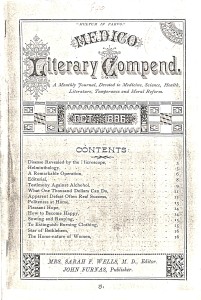

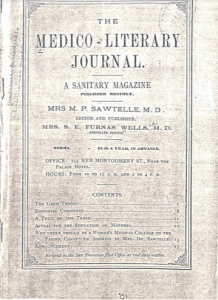

Author: Sarah Furnas Wells

Title: An Address at the Opening Exercises of the Woman’s Medical College of the Pacific Coast Date: 1885

Source: Oberlin College Archives, 30/145, Box No. 2, Other Individuals, Dr. A. Clair Siddall, folder 1

Document Type: Printed Document

This is an excerpt from Ten Years’ Travel Around the World. It is transcribed from a photocopy of the original book found in A. Clair Siddall’s research files.

Ten Years’ Travel chronicles Wells’ years of global traveling, learning, teaching and medical work. When writing of her stay in San Francisco, she reproduced the speech she gave at the opening exercises of the Woman’s Medical College of the Pacific Coast, founded in collaboration with Mary Sawtelle. On 14 November 1881, Wells and Sawtelle officially received the incorporation papers for the school. Both women served as trustees for one year, and Wells served as President until she left San Francisco on 12 May 1882.

In her speech, Wells traced the history of women in Western medicine, an outstanding argument for women’s advancement in the professional world, as well as her own journeys in Europe. Near the end, Wells relied on the rhetoric of moral reform, asserting that women belonged in the medical profession to fulfill their duty of advancing human welfare.

OPENING ADDRESS.

AN ADDRESS AT THE OPENING EXERCISES OF THE WOMAN’S MEDICAL COLLEGE OF THE PACIFIC COAST, BY MRS. SARAH FURNAS WELLS, M. D., PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE.

WOMEN IN MEDICINE AND THEIR COLLEGES.

In tracing the history of medicine, we find from the earliest times, the names of women gifted in the healing art, and possessed of a knowledge of drugs and their application. Before the present schools of medicine, women were virtually the physicians of the world. Aspasia practiced medicine at Rome in the third century, and wrote a book on the diseases of women. Cleopatra’s works are often quoted with favor1. In the thirteenth century Tortula3 [sic], an Arabian woman, published a treatise in which she makes mention that many Saracenic4 women practiced obstetrics at Solerno4.

In the latter part of the eighteenth century, Madonna Manzolina6 lectured on anatomy at Bologna, while other ladies filled subordinate positions. Agnodice7 so distinguished herself in the practice of medicine, that a law was passed, allowing all free-born Grecian women to practice medicine. A social reform began to set in, affecting all classes of society. The breaking up of the old system, and the introduction of a new order of thought. [sic] Women now began to take a more important role in the affairs of social life. In western Europe, women became noted and brilliant in history.

The present century has witnessed the founding of many colleges by women, and for their intellectual and scientific culture. Catharine [sic] II. [sic] opened colleges and hospitals for women, and secured teachers to instruct them as nurses8. Queen’s College9, which was opened in 1853, and to which a royal charter was granted, is under the supervision of the Bishop of London. Previous to the founding of colleges for women, we find them contributing largely to the founding of colleges for the opposite sex. In the University of Cambridge10, containing thirteen colleges and four halls, we find the names of women active in the work of endowing that institution. Clare Hall11 and Pembroke Hall12 were founded by ladies. Margaret of Anjou13 founded and partly endowed Queen’s [sic] College14. Christ’s College15 was endowed by a lady. In England, women first became distinguished in art, literature, and the drama. The queens of the drama have swayed the world, and won for themselves the brightest honors. They were necessary to the development of art.

In England, women made no progress in the study of medicine for years. The first movement in that direction was made by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson16, who, after years of opposition, received her degree in medicine, and now has a lucrative practice in London. She has opened a hospital for women and children. Associated with her is a lady graduate, of continental Europe.

In 1871, at the time of my second visit to England, the most intense excitement prevailed throughout the British Isles, over the rejection of Mrs. Jex Blake17, upon her presenting herself for graduation and passing the preseribed [sic] examinations. Ladies of rank rose in her behalf. Subscription to the amount of many hundred pounds sterling were raised, and at last the degree was granted.

Mrs. McLaren, the wife of a Member of Parliament from Edinburg [sic], on learning of my arrival in London from Vienna, where I had studied and received certificates on practical subjects in medicine, came to see me. On hearing me relate my experience. [sic] she remarked: ‘The Americans have just cause to be proud of you, for you have displayed as much courage as the soldier who takes his place in the army, and you merit as much honor as the victorious general from the field of battle.’ She took me with her in her carriage to the closing of the Houses of Parliament. Afterwards, in Edinburg, I was her guest at her house.

In the United States, long before this movement began in England, the Medical profession was open to women. When the question was first agitated, the medical colleges closed their doors against them, and even the advantages of hospitals was refused them. Colleges were therefore founded for the purpose of teaching women. The ladies of our own country who were the first to adopt medicine as a profession, were those who opened the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia, and the Medical College for Women in Boston, and the three Medical Colleges in New York18. In Philadelphia, in a building north of Girard College19, I attended my first course of medical lectures. Three devoted women, some thirty years ago, were seen going the dull rounds of duty day by day. The burden was heavy, but time has proved how well it was borne. The names of Dr. Emeline Horton Cleveland20, Dr. Ann Preston21, and Dr. Mary J. Scarlet22, shine as brilliant gems in the diadem of medical fame. This institution is now richly endowed, and is one of the best in the country. About the same time the Blackwell sisters23 were engaged in New York, in laying the foundation of what is now a college of equal renown. Of all the women in medicine, none by her individual efforts has achieved such success as Dr. Clemence S. Lozier24, Dean and Emeritus professor of the New York Medical College for Women–now a department of the University of New York–my own cherished Alma Mater. By the persevering efforts of this distinguished lady, a college and hospital was founded. Our building in New York was a brown stone front, worth forty thousand dollars, with apparatus obtained from Paris, for illustrating lectures, worth six thousand dollars.

Mrs. Lozier and others, [sic] opened the doors of Bellvue [sic] Hospital25 to women, gained access to the Eye and Ear Infirmary26, Dr. Sim’s Clinics27, and the great Hospitals of Ward’s Island28. In all her public work and private practice, Dr. Lozier has preserved the dignity and sweetness of a true woman.

At the time of my graduation, there was a demand for ladies to fill professorships in medicine. I was selected by the trustees for a chair in Anatomy. My classmate, Mrs. Charlotte I. Lozier29, was selected to fill a chair in Physiology. At her death, both professorships were conferred on me, which I held until called by the faculty to the chair in Obstetrics. To qualify myself for the responsible duties of this position, I went to the hospital at Vienna, Austria, one of the largest in the world, under the care of eminent men in the medical profession30. As I passed through Berlin, the coaches were filled with wounded and dying soldiers from the Franco-Prussian war, then raging in Europe31. When I arrived at Vienna, I found the Typhus fever32 prevaing [sic], but this did not deter me from my course. To my surprise the utmost courtesy was shown me by the men of science; the best opportunities were offered me to study the subject in all its scientific bearings. Such privileges, and a deep devotion to my profession, served to gain respect at the clinics from the hundreds of students from all parts of the world. In surgical operations I received the applause of the professors and students, and was granted certificates of the same degree as those received by the men. I returned and filled the chair to which I had been elected, with satisfaction to trustees and students.

For one, I am deeply interested in the Woman’s Medical College, Hospital, and Dispensary of the Pacific Coast33. Less than half a century has elapsed since the news of California’s fabulous wealth has called to her shores the tide of immigration. She now holds rank with her older sister states in science, art, and wealth. Behold the mighty change. Where the hamlet once stood, now taste, wealth, culture, and enterprise, [sic] have erected this noble city, and embellished it with the decorations of fancy.

Our meeting this evening for the opening of the Woman’s College of the Pacific Coast, is an event worthy the records [sic] of the march of progress. To woman’s advancement, more liberality and courtesy could not be shown in any part of the world, and a more favored spot could not be selected. The idea was barely suggested when it was caught up and impelled onward with a force that surprised its originators.

This evening, we, the incorporators of the enterprise, are before you to impress you with the importance of this work. Woman and her work is one of the great questions of the age. She, as well as man, has a duty to be discharged for the welfare of humanity. The number of cultured women now engaged in the practice of medicine have demonstrated their ability and fitness to perform the duties with as much honor and dignity as men. The medical education of women is no longer a question. To-day, no plea, no apology is needed. It is demanded by dictates of justice, and it must be carried to the higher spheres of the profession. It is the aim of this institution to offer woman an opportunity to qualify herself to take rank in the profession, and as she does so, to put her shoulder to the wheel of progress, and advance, not only her own welfare, but that of mankind in general.

Transcribed by Abby Bisesi.

1 Aspasia (fl. fourth century CE) was a Greek woman physician responsible for many breakthroughs and innovations in surgery, obstetrics, and gynecology, including surgical abortion. Her work and writings were widely cited and highly regarded by her contemporaries, but most of her texts are lost today (George Androutsos, Antonis A. Kousoulis and Gregory Tsoucalas, “Innovative Surgical Techniques of Aspasia, the Early Greek Gynecologist,” Surgical Innovation 19 (2012): 337-338).

2Some texts on gynecology and disease treatment are attributed to Cleopatra VII (51-30 BCE), the last active pharaoh of Ancient Egypt (Joseph Geiger, “Cleopatra the Physician,” Zutot 1 (2001): 28-32).

3 Trota di Ruggiero, also know as Trotula of Solerno, was born circa 1090 in Solerno, Italy. Wells seems to have misspelled her name, as it is usually spelled “Trotula.” She studied and worked as a professor of medicine at the Scuola Medica Salernitana, focusing on obstetrics and gynecology (“Trota of Solerno,” Encyclopedia of World Biography, last modified 2005, accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

4 “Saracenic” referred to people of Syrian and/or Arabic descent (“Saracenic,” Dictionary.com, last modified 2010, accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

5 During the High Middle Ages (c. 1000-1300), the Scuola Medica Salernitana was a center of the medical profession; it is widely seen as the first medical school of the Western world. It boasted a progressive approach to medicine, incorporating three primary scientific traditions: European, Islamic and Greek. It was also one of the few institutions where women were allowed to attend and teach. Trota’s date of death is unknown. She is known to have written three medical texts: Practica secundum Trotam (Practical medicine according to Trota), De egritudinum curatione (On the treatment of illnesses), and On Treatments for Women. It is unclear which of them Wells referenced here (Jackie Rosenhek, “Medicine woman,” Doctor’s Review, May 2008, accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

6 Madonna Manzolina (fl. eighteenth century) obtained a degree in surgery and was a professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna. Located in Bologna, Italy, the University of Bologna was founded in 1088, and is considered the oldest university in the world (“University from the 12th to the 20th Century–University of Bologna,” University of Bologna, last modified 2015, web address.) ( Elizabeth Peake, Pen Pictures of Europe (Kessinger Publishing, 1874), 273).

7Agnodice (fl. fourth century BCE) was the first recorded woman physician, midwife and gynecologist in Athens, although her historicity is disputed. She reportedly disguised herself as a man in order to study medicine in Alexandria before graduating and returning to Athens to practice. Allegedly, though she continued to disguise herself as a man, Agnodice’s identity as a woman was a well-known secret among mothers-to-be in Athens, ensuring her popularity as an attending physician during childbirth. As a result, other physicians in the city grew jealous of her success and began accusing her of seducing and raping victims. In order to protect her honor and reputation, Agnodice revealed her femaleness and was promptly arrested, as it was illegal for women to practice medicine in Athens. However, an angry mob of wealthy Athenian women whom Agnodice had helped in childbirth quickly came to her rescue, and the law banning women from medical practice was ultimately rescinded, so long as they only treated female patients (Jackie Rosenhek, “The art and artifice of Agnodice,” Doctor’s Review, April 2005, accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

8 Catherine II (1729-1796), also known as Catherine the Great, was the daughter of a German prince. She married Peter III, heir to the Russian throne, in 1744, and became Empress of Russia in July 1762. She is well-known for her commitment to the westernization of the Russian Empire. She funded the Smolny Institute for Noble Girls, the first all-female educational institution in the Empire (“Catherine the Great,” History UK, accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

9Queen’s College is a school for girls in Westminster, London, founded in 1848 by Frederick Denison Maurice, a Professor of literature and history at King’s College, also in London. It was the first girls’ school to receive a royal charter (Frances Ramsey, “About Queen’s College London,” accessed 3 May 2015, web address.)

10The University of Cambridge, in Cambridge, England, was founded in 1209. Today it is made up of thirty-one colleges. The sixteen colleges in 1885 were Christ’s College, Corpus Christi College, Downing College, Emmanuel College, Girton College, Gonville and Caius College, Jesus College, King’s College, Magdalene College, Peterhouse College, Queens’ College, St. John’s College, Trinity College, Sidney Sussex College, Newnham College and St. Catherine’s College. The four halls of the University of Cambridge at the time of Wells’ speech were Fitzwilliam Hall (now Fitzwilliam College), Clare Hall (now Clare College), Pembroke Hall (now Pembroke College), and Trinity Hall (“Early Records,” University of Cambridge, last modified 2015, accessed 3 May 2015, web address); (“Cambridge Through the Centuries,” University of Cambridge, last modified 2015, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

11 Clare College is the second-oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge, initially founded in 1326. In 1338, it was refounded as Clare Hall by an endowment from Elizabeth de Clare (1295-1360), granddaughter of Edward I. (Michael Lapidge, “College History,” last modified 2014, accessed 3 May 2015, web address); (Suzanne Paul, “The Breviary of Marie de St Pol,” last modified 2011, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

12Pembroke College is the third-oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge, established in 1347. It was initially named the Hall of Valence Mary in honor of its founder Marie de St. Pol (c. 1304-1377), widow of the Earl of Pembroke. The Hall was renamed Pembroke Hall at an unknown date, and then finally renamed Pembroke College in 1856 (“Pembroke Past and Present,” Pembroke College, Cambridge, last modified 2012, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

13Margaret of Anjou (1430-1482) was Queen of England and wife of Henry IV (“Chronology,” Queens’ College Cambridge, last modified 2015, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

14Queen’s College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou and refounded in 1465 by Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of Edward IV, hence its moniker Queens’ instead of Queen’s (“Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England (1430-1482),” Encyclopedia Britannica 17 (Cambridge: Cambridge university Press, 1910), 703).

15Christ’s College was founded in 1505 by Lady Margaret Beaufort (1443-1509), the Countess of Richmond and Derby, mother of King Henry VII and grandmother of Henry VIII. St. John’s College was founded by her estate in 1511 after her death (“The History of Christ’s College,” Christ’s College Cambridge, last modified 30 April 2014, accessed 3 May 2015, web address); (Michael Jones, “Lady Margaret Beaufort,” History Today 35, 8 August 1985, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

16 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) attempted to study medicine for years, enrolling as a nursing student at Middlesex Hospital until she was asked to leave due to complaints from male students. Garrett Anderson taught herself French and earned her medical degree from La Sorbonne in Paris, though the British Medical Register refused to acknowledge her certification. In 1872, Anderson founded the New Hospital for Women in London. An act was passed in 1876 permitting women to study medicine, and in 1883 Anderson was appointed Dean of the London School of Medicine for Women, which she had helped to found in 1874 (“Elizabeth Garrett Anderson,” BBC.com, last modified 2014, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

17Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) was a physician born in Hastings, England. She attended Queen’s College in London and was later admitted to classes in medicine at the University of Edinburgh along with six other women (known as the Edinburgh Seven) who were required to fund their own gender-segregated lectures and not allowed to take degrees. In 1874, Jex-Blake helped Elizabeth Garrett Anderson found the London School of Medicine. In 1877, she was awarded an M.D. from the University of Berne; a few months later, she qualified as Licentiate of the King’s and Queen’s College of Physicians of Ireland and became the third registered woman doctor in Great Britain (“Sophia Jex-Blake,” Encyclopedia of World Biography, last modified 2004, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

18 The Female Medical College of Pennsylvania, later the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, was founded in 1850 by Dr. Bartholomew Fussell as a tribute to his deceased sister, in collaboration with the rest of the Fussell family and businessman William J. Mullen (Sylvain Cazalet, “Female Medical College of Pennsylvania and Homeopathic Medical College of Pennsylvania,” last modified 2004, accessed 3 May 2015, web address). (Sylvain Cazalet, “New England Female Medical College and New England Hospital for Women and Children,” last modified 2001, accessed 3 May 2015, web address). The Boston Female Medical College, later renamed the New England Female Medical College, was founded in 1848 by Dr. Samuel Gregory and Dr. Israel Tilsdale Talbot. It was the first medical school for women in the world (Sylvain Cazalet, “History of the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women,” last modified 2001, accessed 5 May 2015, web address). (“Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell,” National Library of Medicine, accessed May 3, 2015, web address). The first two medical colleges in New York founded by and open only to women were the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary and the New York Medical College for Women. The Geneva Medical College and the Syracuse Medical College also accepted and graduated women doctors, including Elizabeth Blackwell (graduate of the former) and Clemence Lozier, a graduate of the latter (Maggie MacLean, “Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier,” History of American Women, 28 March 2014, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

19Girard College is a boarding preparatory school located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded in 1833 by businessman Stephen Girard (1750-1831) to educate poor, white orphaned boys (Sandra L. Chaff to Alcines Clair Siddall, M.D., 20 June 1977, A. Clair Siddall Papers, 1918-1988, Record Group: Other Individuals, Box 2, Oberlin College Archives). Wells was a student at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania during the 1865-1866 session, though she did not graduate (Elizabeth Laurent, “Girard College: History,” last modified 2010, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

20Dr. Emeline Horton Cleveland (1829-1878) attended Oberlin College in 1850 with dreams of doing missionary work. After her graduation in August 1853, she enrolled at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Following her graduation from the Medical College in 1855, she set up a practice in New York’s Oneida Valley. In 1856, Dr. Cleveland was invited back to the Woman’s Medical College to teach anatomy, where she remained until 1860. Cleveland became chief resident at the newly established Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia, established by Dr. Ann Preston, in 1862. She succeeded Preston as Dean of the W. M. C. P. in 1872, and in 1878 she was appointed gynecologist at Pennsylvania’s Hospital Department for the Insane, making her one of the first woman physicians in the United States to be hired by a major public medical institution (“Dr. Emeline Horton Cleveland,” National Library of Medicine, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

21 In the 1840s, Dr. Ann Preston (1813-1872) began teaching physiology and hygiene to women in order to educate them about their bodies. In 1847, she applied to four medical colleges in Philadelphia before attending the W. M. C. P. after its founding in 1850. She graduated in 1851 and was appointed Professor of physiology and hygiene at the college in 1853. In 1861, she organized a board of women to fund and run a women’s hospital where female students could gain clinical experience. Preston became the first woman Dean of the W. M. C. P. in 1866, and was elected to the college’s Board in 1867. In 1869, she arranged for her students to attend general clinics at the Pennsylvania Hospital and accompanied them to the very first clinic in solidarity against the ensuing harassment by male students (“Dr. Ann Preston,” National Library of Medicine, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

22Dr. Mary J. Scarlett-Dixon (1822-1900) was born in Robeson, Pennsylvania. She attended the W. M. C. P. in 1855, graduating in 1857. She was well-known for taking poor patients, and in 1859 she was appointed demonstrator of anatomy and assistant physician at the W. M. C. P. From 1868 to 1871 she served as resident physician at the college. In the later part of her life she was troubled by glaucoma, though she still continued to practice medicine.

23Drs. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) and Emily Blackwell (1826-1910) were born in Bristol, England. Elizabeth became the first woman to receive an M.D. from an American medical school after graduating from Geneva Medical College in New York. She had been admitted as a joke by the faculty, who had assumed that the all-male student body would revolt against a woman joining the college. In collaboration with her sister and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, Elizabeth opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857; an associated college was established in 1868. The institution was intended to provide experience for women doctors and medical care for the poor. Dr. Emily Blackwell earned an M.D. from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1854 after several years of rejection from various schools across the country. Emily ran the New York Infirmary for forty years following its establishment. After its initial opening, it was staffed with fifteen students and nine faculty. Elizabeth was Professor of Hygiene and Emily served as Professor of Obstetrics and Women’s Diseases (“Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell;” “Dr. Emily Blackwell,” National Library of Medicine, accessed 3 May, 2015, web address).

24 Dr. Clemence Sophia Harned Lozier (1813-1888) was admitted to the Eclectic Medical Institute of New York in 1847. When Lozier graduated in 1853, the school had become the Syracuse Medical College. Lozier then opened a practice in obstetrics and gynecology. In 1867, Lozier became President, Dean and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the New York Medical College and Hospital for Women, where she remained until her death (“A Brief History of New York University,” New York University, accessed 5 May 2015, web address). Wells is probably referring to New York University, initially named the University of the City of New York.

25 Bellevue Hospital Center was founded in 1736 and is the oldest public hospital in America. Through the efforts of Drs. Charlotte Denman Lozier and Clemence S. Lozier, Bellevue Hospital allowed female medical students to attend clinics there in 1863, although women could not work as interns at the hospital until the early twentieth century (“History–About Bellevue,” last modified 2014, accessed 4 May 2015, web address).

26The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, established in 1820 by Edward Delafield and John Kearney Rodgers, allowed women to train and work as nurses at the institution (“New York Eye and Ear Infirmary History,” New York Ear and Eye Infirmary of Mount Sinai, accessed 4 May 2015, web address).

27J. Marion Sims (1813-1844) is considered the father of gynecology due to his revolutionary approaches to treating women’s health. He founded the Woman’s Hospital in New York in 1855 (Jeffrey S. Sartin, “J. Marion Sims, the Father of Gynecology: Hero or Villain?” Southern Medical Journal 97(5), May 2004, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

28At the time of Wells’ address, Ward’s Island (now Wards Island) of Manhattan was home to the New York City Insane Asylum and the Verplank State Emigrant Hospital (“Ward’s Island,” Inmates of Willard, last modified 24 May 2013, accessed 5 May 2015, web address); (“Wards Islands Refugees,” Yonder Places, accessed 5 May 2015, web address).

29 Dr. Charlotte Denman Lozier (1844-1870) was a physician and Professor at the New York Medical College for Women. She attended the Medical College in 1864, where she met Sarah Furnas Wells. Upon her graduation, she was offered a professorship in physiology at the Medical College. Lozier is best known for her passionate defense of Hester Vaughan, an English immigrant woman arrested in 1868 in New York for killing her newborn infant (actually, the infant died because Vaughan could not afford medical attention–she gave birth in an unheated garret in wintertime and the child died of exposure). With the aid of Lozier and other notable feminists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Vaughan was pardoned six months after her arrest (Maggie MacLean, “Charlotte Denman Lozier,” History of American Women, 2 February 2015, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

30Wells went to Vienna in 1871 to study at the Vienna General Hospital (Allgemeines Krankenhaus), where she supervised the clinics of a Dr. Braun. She passed her course and exams there, receiving her certification along with the male students.

31The Franco-Prussian War lasted from July 1870 to May 1871. A coalition of German states, led by Prussia and its chancellor Otto von Bismarck, defeated France, ruled by Napoleon III. The end of the war resulted in the unification of Germany (“Franco-German War,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified 20 November 2014, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

32Epidemic typhus is also known as camp fever, jail fever and war fever, since the disease is most prevalent in areas of overcrowding and low standards of hygiene. The rickettsia bacteria that causes typhus is louse-borne, and the symptoms include headache, fever, chills, rash and toxemia. Although there are no records of an unusual outbreak of typhus in Vienna during the Franco-Prussian War, the conflict negatively affected living conditions in the involved countries (“Typhus,” Encyclopedia Britannica, last modified 24 November 2015, accessed 3 May 2015, web address).

33 The date of the opening is not given, but probably took place in late November or early December 1881, since the school was chartered in early November 1881 and Wells left San Francisco in May 1882. She wrote that she spent five months at the college (Wells, Ten Years’ Travel, 548-554).