Lucy Angela Woodcock, sister to Henry Woodcock, was born in Independence, New York, on 16 June 1822.1 After her brother had gone to Oberlin College, their mother suggested that she join him there. According to his autobiography, Henry was overjoyed to accept this, and became particularly close to Lucy during their years together at Oberlin.2 This relationship seems to have been founded in part on the deep religious convictions they shared (which the rest of their family apparently lacked), as well as on their shared commitments to abolition. At the time, Oberlin was a stop on the Underground Railroad and both the college and the town were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement. Though there is no information on whether or not Lucy Woodcock participated in any specific abolitionist organizations, her later letters to her brother reveal that the cause often occupied her thoughts. Henry Woodcock also advocated for abolition throughout his life, and, like his devotion to temperance, his ardent attachment to his cause sometimes got him into trouble, and even cost him his job at one New York pastorate.3 These shared passions for religion and abolition, as well as their shared experience at Oberlin, cemented the relationship between Henry and Lucy.

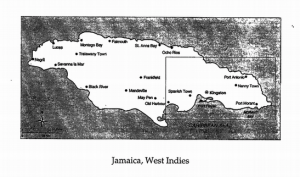

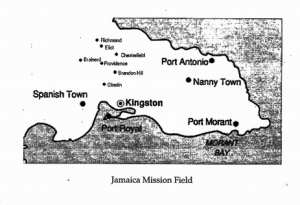

After she had completed her Ladies’ course, Lucy initially found work as a teacher, but then moved into Henry’s home after the death of his first wife, Elizabeth Hurlbut Woodcock. Until his marriage to Lucy Hatch Thayer a year later, she kept house for Henry and cared for his young son, Arthur. He also credits her with aiding him in his pastoral work at the time.4 After Henry’s remarriage, she was able to accept a post in Jamaica offered to her by the American Missionary Association. Lucy likely chose this post because of her commitment to abolition and the uplift of emancipated slaves; though slavery was abolished in Jamaica before her arrival on the island, many of the inequalities created by slavery continued to exist. Lucy remained a missionary on the island for twenty-two years, until just before her death. She died in Wellsville, New York, on 3 August 1876, after seeking treatment for what was likely breast cancer.5

Lucy’s work with the mission was not easy. Founded by Oberlin graduates, the Jamaican mission she worked at was often wracked with tensions, due to both internal problems and a lack of funding.6 The climate was also harsh, and many of the missionaries died or were severely incapacitated by illness.7 Lucy was one of the longest-serving missionaries, and her peers, who seem to have respected her greatly, recognized her dedication.8

Despite her strong religious belief, Lucy was a very independent woman and her missionary work often placed her in positions of authority; for a time she was in charge of the entire Eliot Mission. Though women were seen as reasonable voices of moral authority during this era, the degree of Lucy’s independence and influence in her missionary work was unusual for a woman, as was her unwedded state. Her letters to Henry, three of which are included in this mini-collection, reveal a thoughtful and extremely intelligent woman who was perfectly content living outside the traditional roles of wife and mother.

Lucy’s letters also reveal the character of her relationship with her brother. While she visited home only once during her years as a missionary, she and Henry kept up a lively correspondence.9 Though Lucy’s papers were destroyed after her death in 1876, Henry preserved all of the letters she had sent him in a touching display of sibling love.10 Alternately serious and inconsequential, colloquial and grandiloquent, sentimental and playful, Lucy’s letters to Henry reveal not only her own distinct personality, but the degree of their friendship. Lucy trusted Henry to take her work and her feelings seriously, despite her gender. Their understanding of one another went beyond the limits of traditional male and female roles. Lucy felt comfortable complaining to Henry about her fellow missionaries and sharing family gossip without seeming to worry that he would find her frivolous or over-emotional. In the same letters, she would also discuss the more philosophical aspects of her work and present her own thoughts and feelings on the mission and Christianity. Despite the fact that it was not commonly considered appropriate for women to preach or wield independent authority, Henry seems to have encouraged her to share all her thoughts, and taken both them and her work as a missionary seriously. He was himself a minister, and though Lucy was in Jamaica when he founded his church in Tonganoxie, Kansas, she was also credited as one of the founders.11 In her letter to him after the death of their father, she clearly felt comfortable turning to him in times of emotional turmoil, and she missed him dearly, as she tells him: “We as a family have been spared these Many years to go out and come in to greet each other face to face, but it is so no more. I did want to come home this year.”12 Her letters suggest that she felt she could be herself around him, free from judgement or chiding. Though other men of this period had a tendency to idealize women, particularly religious ones, as pure figures of extreme moral rectitude, Henry seems to have accepted his sister’s imperfections.

Henry’s autobiography confirms how highly he thought of her; however, his writings and her letters also reveal the ways in which Lucy’s successful independence was often complicated by her gender. She was the only one of Henry’s sisters to attend college, and even then, she was forced to leave Oberlin for at least a semester when her oldest sister, Eliza Marie Jones, suffered from what appears to have been a nervous breakdown.13 Lucy, as the oldest unmarried sister, had to take care of her sister’s house. Similarly, though she wished to go to Jamaica immediately after attending Oberlin, she remained with Henry until his remarriage. While she was able to stay in Jamaica eventually, those in charge of the mission were reluctant to have young single women serve.14

While we do not have any of Lucy’s own thoughts on these potential setbacks, Henry’s writing makes it clear that he felt that Lucy was right to put her role as a sister above her own desires for an education and missionary work. However, despite this, he treated her as an absolute intellectual equal and friend, and her own letters, reveal that she felt comfortable confiding anything to Henry. Lucy’s display of trust suggests that while gendered roles and limitations were still seen as the unquestioned norm for women, some men supported women in efforts that went beyond such roles.

1Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Series 2. Writings. 1987/67. 1989/141. RG 30/81.

2Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Series 4. Files Relating to the Woodcock Family.

3His autobiography states that various members of the town declined to provide funding for his pastorate after his support of abolition became public (Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers, Series 4. Files Relating to the Woodcock Family).

4Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Microfilm.

5The Congregational Quarterly, Vol. 19 1877; Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. 1987/67. 1989/141. RG 30/81.

6Gale L. Kenny, Contentious Liberties: American Abolitionists in Post-Emancipation Jamaica, 1834-1866. Race in Atlantic World 1700-1900 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010).

7Charles G. Gosselink, Sarah Corban Ingraham Penfield, and Thornton Bigelow Penfield, Letters from Jamaica :1858-1866 : Thornton Bigelow Penfield, Sarah Ingraham Penfield (Silver Bay, NY: Boat House Books, 2005).

8Thorden and Sarah Penfield, some of the other Oberlin missionaries, frequently mentioned Lucy Woodcock in their own letters. In one letter, Thorden seems to place her among the most influential people in the mission, all the rest of whom were male (Gosselink, Letters from Jamaica, 51).

9Her visit was for several months, starting in April of 1861. It was likely so long because the mission was lacking funds, and very nearly didn’t rehire Lucy. It is possible that when Lucy went back to Jamaica, she ended up living for a time entirely on the charity of the locals, without any payment from the mission (Gosselink, Letters from Jamaica, 114-122).

10John McLeod to Henry Woodcock, 27 December, 1876 (Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers).

11Commemorative plate marking the 125th anniversary of the founding of Tonganoxie, Kansas First Congregational Church, United Church of Christ’s founding. Oberlin College Archives.

12Lucy Woodcock to Henry Woodcock, 8 August 1860 (quote edited for clarity, see letter for original.) Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Series 1. Correspondence. 1987/67. 1989/141. RG 30/81.

13In his autobiography, Henry Woodcock states Eliza suffered from “nervous prostration.” (Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers, Series 4. Files Relating to the Woodcock Family).

14An unwedded colleague of Lucy’s, whom she mentions in her early letters and refers to as a close friend, was forced to leave the mission after its male heads began to feel that she was acting too autonomously. The combination of her gender and her single-state made her less reputable and more unruly in the eyes of the male missionaries (Gale L. Kenny, Contentious Liberties: American Abolitionists in Post-Emancipation Jamaica, 1834-1866. Race in Atlantic World 1700-1900 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2010).