The letters in this part of the collection document the beginnings of the correspondence between a young Henry Woodcock and the woman who would become his second wife, Lucy Hatch Thayer, while Henry was a serving as a pastor in Nelson, Pennsylvania.1

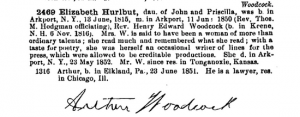

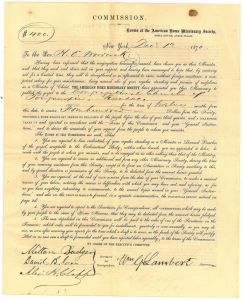

Henry Woodcock became a widower in 1852 following the death of his first wife, Elizabeth Hurlbut, after only three years of marriage.2 His beloved younger sister, Lucy Angela Woodcock, stepped in to keep his house and to help him raise his son. Despite his high praise for his sister, and the close relationship they clearly shared, he soon began to seek out another woman who could, in his words, be a true companion to him and share in his labours. This likely reflected his own feelings about the importance of certain traditional gender roles, but also seems to have been partially motivated by the fact that his sister had been granted a position as a missionary in Jamaica, and was eager to accept the post.3 With this somewhat contrary combination of desires to both allow his sister to pursue her own work and find a woman who could support him as a minister, he began to pursue a young woman from the nearby town of Lawrenceville as a possible spouse.

The woman in question, Lucy Hatch Thayer, had taught at a select school for young women in the area, and two of her students were parishioners of Henry’s. According to his autobiography, he first heard of Lucy Thayer through them.4 As she was no longer living in the area, having accepted a new teaching position some distance away in Dunkirk, New York, Henry approached her adoptive father, the Reverend E. D. Wells, with intentions to court her. Henry was already well acquainted with Wells, who had been responsible for him obtaining his pastorate in Nelson, and seems to have liked and respected Henry. After receiving Wells’ permission and encouragement, Henry went to Dunkirk, New York, where he finally met Lucy Thayer. Though Thayer did not know of his intent to court her at the time of the visit, Henry wrote to her immediately afterwards, declaring both his desire to begin a correspondence with her, and his hope that their correspondence would end in matrimony. This letter, and Thayer’s agreeable response, form the beginning of this mini-collection.

Though parts of the letters read as quite romantic, the almost business-like sentiment that emerges in places reflects the continued influence of traditions and essentialist gender roles, even on men as committed to equality and social reform as Henry claimed to be. Though they appear to have been attracted to each other, this is not a story of love at first sight but a tale of how gendered expectations for men and women played out in nineteenth-century courtships. Henry speaks quite frankly of his need for a wife, almost describing it as a job for which he is hiring. Lucy furthers this impression, writing “I cannot doubt that you are worthy of myself not only, but of one far better qualified to meet the duties and responsibilities of a Pastor’s wife.”5 They both show accept the right and necessity for Henry to have a wife to support him and be a mother to his son Arthur. Both Henry and Lucy Thayer place special importance on the role of a mother in a child’s life, and clearly feel that being raised simply by a father, or even by an aunt, would mean the child was lacking something critical.

Apart from this notion of Henry’s need for a wife, other less visible indications of gendered roles and assumptions are also present in these letters, most notably in the levels of interest Henry and Lucy express for each other aside from discussing marriage. Henry speaks little with Lucy about matters other than his role as minister and his own feeling of general exuberance. Lucy, on the other hand, speaks in depth of her interests in teaching and the temperance movement, and even seeks Henry’s advice on each of these matters. Clearly that she views Henry not only as a potential “employer” with whom she can adequately administer to her duties as a woman, but as a true companion, who shares her interests and has interests of his own. While Henry may have felt the same towards her, his first letter does not indicate it.

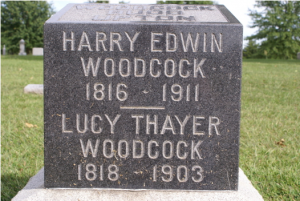

These initial courtship letters of Henry Woodcock and Lucy Thayer serve as examples of ways in which gender roles permeated notions of marriage and courtship in antebellum society, and of the role a woman was expected to have. However, despite its decidedly less romantic aspects, the union that emerged from these letters was both long-lasting and extremely loving.

1Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. 1987/67. 1989/141. RG 30/81.

2Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Series 2. Writings.

3Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Microfilm.

4Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers. Series 4. Files Relating to the Woodcock Family.

5Lucy Thayer’s 1853 letter to Henry Woodcock. (Oberlin College Archives, The Henry Edwin Woodcock Papers).