Document 3: 1929 Letter

Author: Luella Miner

Recipient: Unknown American(s)

Date: 6 September 1929

Source: Student File: Sarah Luella Miner, Record Group 28/2, Oberlin College Archives

Document Type: Typed letter

In Luella Miner’s student file, there is a photocopy of a typewritten document, ostensibly a letter written to friends in the United States. It reveals the connections of her Chinese acquaintances to the military and the government of the Chinese Republic. She maintained close friendships with several of her Chinese former students. Those with influence in Chinese society (like H. H. Kung1) were connected with the Kuomintang (Nationalist) political party, which explains her concern for the political situation.

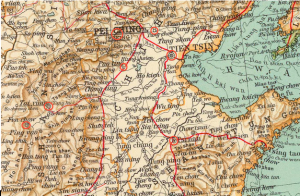

At the time of her writing this, Miner was residing in Shansi province, a longtime site of Oberlin missionary efforts, but she was not affiliated with the so-called Oberlin Band, a group of early missionaries killed in the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion.

She survived, and a biographical sketch of her2 describes her as “one of the heroines of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.” But Miner did stand against the Boxers, who fought to eradicate foreign influence and killed all Oberlin missionaries staying in Shansi and even Chinese converts. Miner referred to the Boxers as “wild beasts” and “madmen,” even though she treated their Christian counterparts with as much respect as she did Western missionaries. She wrote,

It seems so strange to be cut off from our Chinese friends. . . To me their love and friendship means very much, taking a place which in some respects cannot be filled by intercourse with foreigners. Some missionaries seem to work with the Chinese at arms length as it were, and are a little inclined to criticize those of us who treat them fully as equals and let them see that we regard them as personal friends, but these are the exception. In a way I think that the Chinese feel that they have a special claim upon us unmarried missionaries. They realize that we have no cares or affections that can hinder us from entering fully into their joys and sorrows3.

Miner held complex views on cultural difference, religion and imperialism. According to her, “No hearts in the [Chinese] empire were more deeply stirred by the territorial aggressions of European powers than were those of students in mission colleges4.” Although she believed Christianity essential to civilizing people, she respected the Chinese as people to a degree other Westerners did not, as revealed in her China’s Book of Martyrs. Other Westerners writing about the Boxer Rebellion devoted their attention to the Westerners killed. Her book, meanwhile, is full of alleged accounts from Chinese Christians who witnessed and survived the Rebellion along with accounts of how some of them were “martyred.” She strongly warned readers against being racist towards the Chinese because of the violence of the Boxer Rebellion; she even quoted reports from centuries past of torture committed by Christians.

Miner mentions Liu Lan Hua in this letter, a figure dealt with in focus elsewhere in this collection.

Marshal Feng, noted as an acquaintance of hers, was a warlord of Shaanxi (not Shansi) province at the time. Since the 1911 revolution, when the Kuomintang attempted to establish a democratic republic, China had splintered into regional spheres of power at war with one another. Given her connections with the Kuomintang, Miner would likely have wanted them to reunify China.

Transcription:

Sept. 6.

I am here at the capital of Shansi, Taiyanfu, ready to start tomorrow for Peiping5 and T’unghsien, where I shall visit until time for the Yenching University ceremonies of dedication for its fine campus and buildings. This will make me late for the beginning of work in Cheeloo. But the new dean of women for Cheeloo will travel with me from here to Peiping, and I am too happy for words. It is Mrs. Yui, Liu Lan Hua6, one of my college daughters who after several years of teaching in her Taiku, Shansi home, studied several years in Oberlin and Columbia, and for two years has been principal again of the girls’ school in Taiku. She is a rare woman, and it is only her husband’s loyalty to Marshal Feng, and the probability that he7 will accompany him if he goes abroad soon, that makes it possible for us to get her. I am taking with me also Miss C. C. Wang, a sort of adopted daughter of mine who graduated long ago from Bridgman and the Kindergarten Training School in the women’s college, and seven years ago came with me to Fenchoufu to take charge of the kindergarten. She has been laid aside the past few years with tuberculosis, and though she is much better, and has no cough or fever, she may never be strong again, and arrangements for her may affect my future movements somewhat.

I feel very much rested by my three weeks in the mountain valley with my Fenchou8 friends, and the three different visits, a week in all, at the temporary abiding place of Mrs. Feng at some Shansi springs. Three times they sent a car for me, and the last time Miss Wang came with me and also spent a night at Mrs. Feng’s as she was an old college friend, and it broke her journey to this railway terminus. Mrs. Feng’s third daughter was born August 22nd, and a week later she sent the car for me to come and make her a longer visit. I stayed out to the valley for Miss Wang on my way back to Mrs. Feng’s home. We have had perfect weather the past ten days, the previous heavy rains have brought forth wonderful crops, and these long auto rides have been a delight.

The plans of my semi-imprisoned friends are as indefinite as ever, and so far as I know, so are Gov. Yen’s9. The new governor, an associate of Gov. Yen, has come here, but Yen is still busy with reorganization of the vast armies of himself and Marshal Feng, in consultation with him and representatives of the Minister of War and the Vice-minister of Foreign Affairs, who are associates of Marshal Feng. And probably all of the conditions of their “going abroad hand in hand” supposedly to avert strife, have not yet been fulfilled, among them the forwarding of provisions for the famine sufferers in Shensi [sic], the province west of this, and the northern part of this province. The Nanking government decided to reduce the Northwest Army to about a third of its present size, but funds are not yet available to dismiss over a hundred thousand soldiers, and Yen’s armies also need great sums for reorganization. Possibly the complications with Russia are also delaying operations, for one of the threatened points of attack is Chinese Turkestan, in the extreme northwest.

Possibly strife cannot be averted. The recent plot against Chairman Chiang Kai Shek’s life is symptomatic. There is general unrest, and a feeling that Dr. Sun’s ideals10 for the betterment of living conditions for the masses are being neglected. Some feel that there is far more danger of extreme radicals getting possession of the country if Yen and Feng go abroad, and several here have said that if they go abroad they fear it will not be easy for them to get back. Centralization of government has been accomplished, on the surface, but real unification of aim and spirit seems a dream for the future, and some very loyal Kuomintang adherents admit that their popular slogans and [sic] too empty, and are losing their power except with the thoughtless young. Dr. Sun’s principles and sacrificial spirit must still furnish the means of unification, in the present temper of the nation, but some fuller and more positive content must be given. The time has passed for negations.

Yours sincerely,

Luella Miner

Transcribed by Joanna Wiley

1H. H. Kung, born in Taiku, was a Chinese Christian government official. He became the richest man in China and premier of the Chinese Republic. He was on good enough terms with Miner that he financed her funeral. Kung studied at Oberlin College and Yale University, but needed the intervention of Congress to do so because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. (Carl Jacobson, “H. H. Kung”, Oberlin Shansi Memorial, Web address, accessed 12 July 2015).

2 This sketch is in her Student File, written by an unknown individual after her death.

3 Luella Miner to family, 15 June 1890. Quoted in Jane H. Hunter, The Gospel of Gentility: American Women Missionaries in Turn-of-the-Century China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 189. Hunter found many of Miner’s letters in the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions papers at Harvard.

4 Luella Miner, China’s Book of Martyrs (New York, NY: The Pilgrim Press, 1903), 22.

5 This was the official name of Beijing for a time in the twentieth century. Chiang Kai-Shek, in his 1920s military campaign across China, changed the capital to Nanjing and renamed Beijing, which means “northern capital.”

6Yui was born in Taiku and raised a Christian. She studied and worked in the United States, graduating from Oberlin in 1925. She married in 1928, but judging from this letter continued work in her own right afterward.

7 Miner is probably referring to Yui’s husband (see below; they are both mentioned to be going abroad by name.)

8 There was a stream and mountain springs in this valley, called Yu-Tao Ho.

9Yen Hsi-Shan, Shansi warlord.

10Sun Yat-Sen, first president of the Chinese Republic in 1912 and later from 1919 to 1925.