Document 4: I Kao Shang Ti

Author: Lan Hua Liu Yui

Title: “I Kao Shang Ti: The Story of a Girl, a Will and a Way”

Date: After 1929

Source: Former Student File: Lan Hua Liu. Record Group 28/2, box 1156, Oberlin College Archives.

Document Type: Printed Document

The following is an abridged transcription of an evangelical pamphlet written by Lan Hua Liu Yui. The pamphlet is small and has a red cover; its staples have fallen out. The piece is not dated, but it must have been written after 1929, since the Great Depression is briefly referenced at one point1

.

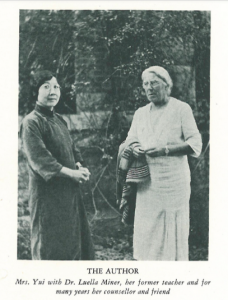

It tells the purportedly true story of a particular exemplary student of Yui’s. Although the title means “Trust in the Lord,” Yui focused not on Christianity but on the girl’s uplift from poverty and development of a path to “service to her people,” revealing what was most important to her. Her approach resembles the political and economic feminism of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Liu wanted to make a difference independently of anyone else, and served as the first female representative of Oberlin College to the Christian schools in Shansi. She also gave lectures in the United States and was principal of a Taiku Christian girls’ school, but lost that position when the school became co-educational and left dissatisfied. The front of her Student File reads “Assumed deceased 4/2000,” which means that hardly any records of her activities exist after her dismissal from the Taiku school. Liu’s words and actions reveal that Luella Miner’s leadership could and did inspire her pupils to develop their own intellect and influence. It is important to note that this is a specific example from a specific mission school, and that attitudes of other female Oberlin missionaries might not have yielded this kind of result.

Compare this pamphlet with Margaret J. Evans’ essay. Whereas Evans viewed the purpose of Western-helmed missions as rescuing souls, Yui presented Christian education as a means to an end. Mei-li, her protagonist, receives a Christian education but also learns to appreciate her unique Chinese heritage. “I Kao Shang Ti” shows the results of mission work to have entailed more than change in religious belief; above all, education provided opportunities for Chinese girls and women to affect the world around them.

Transcription:

Wang Mei-li is a native girl of the Shantung Province, a typical daughter of the Tsao-Hsien district.

Born to a family of small means, she lost her mother at the age of nine, during the years of depression that cost her father his small grocery shop. The father was left to provide for Mei-li, her little brother of six, and a tiny sister of three, as best he could from about two acres of farmland and with the aid of his one horse.

[…]

Now during these dark days Mei-li was comforted by a girl friend who attended a mission school, learning to be a teacher.

“My,” said Mei-li to herself, “how grand if I, too, could teach little children and help my father to feed brother and sister.”

One evening, when her father unloaded the burden from his back, she took courage. “Baba,” said she, “how would you feel if I should go to the mission school to study to be a teacher? It is only a little way.”

Sorrowfully he shook his head. “How can you go to school when there is no one to look after the little ones?” Even the two dollars for tuition, it seemed, was beyond his means.

[…]

Several years passed. Wang Yuan saved his money and one day bought himself a new wife. But in his new-found prosperity and happiness he forgot Mei-li’s ambition to go to school.

One evening the family was seated around the kerosene lamp, when Mei-li re-opened the subject. “Baba,” she inquired, “now that we have our fortune and my stepmother, can’t I go to school?”

The silence that followed was at last broken by the stepmother. “A girl of your age should be getting married and bringing more money to the household,” she said. “I never heard of a girl your age going to school.”

But Wang Yuan knitted his eyebrows together. “You may go for yourself to the mission school and find out tomorrow,” he finally said, and Mei-li was delirious with delight.

[…]

On a day in sunny September her father walked beside her to the school. On his back he carried the small bundle which contained all her belongings–a blue wadded winter gown, a pair of home-made shoes, and a few pieces of summer clothing.

She was warmly received, and soon came to love everything and to enjoy it all. But though she entered into all the activities there, she never neglected her studies.

Time flies as an arrow. In six years she had graduated from the grade school, and was entering a mission junior middle school at Taian, Shantung. Her further education here was made possible through a special fund secured by Miss Brown.

Her new school was located a few miles from Tai Shan, one of the holy mountains of China, revered for its association with the life of Confucius. Here, breathing the wealth of Chinese culture, Mei-li continued her studies. But she discovered that the more she learned, the less she knew.

[…]

So Mei-li went to Ming I Middle School, the motto of which is: “Study hard, work hard, play hard.” And Mei-li was loyal indeed to that motto.

As she had come to the Ming I School from an unregistered school, Mei-li was not able to secure a high school diploma, nor was she allowed to take the government high school graduations examinations.

In the meantime, Mei-li had written to Madame Feng that she hoped to go to college, and particularly to Cheeloo. So one day when Dr. Luella Miner, who had been one of Madame Feng’s teachers, came to Tai Shan, she learned all about Mei-li’s ambition to be a teacher.

“If she wanted to study medicine I could help her with a scholarship,” said Dr. Miner.

When Mei-li talked with Dr. Miner she said, “I have always dreamed of being a teacher, but I had no money and always had to ask the support of other people. When Madame Feng told me of this chance to go to Cheeloo on a scholarship, I realized that I can still be of the same service whether as a doctor, or as a teacher.” She had seen the sick women and children around her country home, and she kept this thought in her heart.

One morning a letter from Mei-li came to me in my office as Dean of Women at Cheeloo. “I am writing to introduce myself,” she began. “I have never seen you but I have heard about you. My principal told me that I can come to see you, as I want so much to come to Cheeloo to study. I have troubles about entrance examinations, but he told me that when I see you in Tsinan you will fix me up. Hoping to see you soon, your humble pupil, Mei-li.”

[…]

There were still three weeks until the University opened, so Mei-li asked me if she might go home to visit her family. When she reached her destination she found the situation very unhappy. Wang Yuan was still working as a servant, but her stepmother was taking all the money and being very cruel to the children.

When Mei-li saw how her sister was being abused and often not getting enough to eat, she decided to take her away, and, with the help of friends, succeeded in getting money to send her to Fengchow Hospital to study nursing. Then she made arrangements for her father to go to Shanghai, and secured work for him with a friend who had a restaurant there. At last, she persuaded her stepmother to return to her own family, taking the younger children with her.

Returning to the University she entered upon her first year of pre-medicine. Though she worked hard and tried to like the work, Science did not like her. Her chemistry was a series of explosions, and the other courses were full of accidents. So, instead of making an enemy of her friend Science, she decided to get acquainted with Rural Education and Sociology. This change she made in the second semester of her freshman year.

One night during supper I notice that Mei-li was not in the dining room. Before long she came in, looking as though she had been struck by a dust storm. “Where have you been?” I asked. Mei-li told me that she had been in a rural village a mile away.

“We learned in Sociology that we should make surveys, so I went to Wang-chia-chuang and made a survey. I asked how many families there are in the village, how the women live, and things like that,” our enthusiastic young social worker replied.

Now at last Mei-li is completely happy. She loves the rural people. She loves her chosen work. She glories in the opportunity for service to her people.

This year Mei-li is a sophomore in Cheeloo University. She is only one of my girls. Can you wonder that I have faith in them and in the future of my country?

Transcribed by Joanna Wiley, 13 July 2015

1 The sentence is not in the transcription. It reads “On account of the depression in America, people are discontinuing their help” (7).