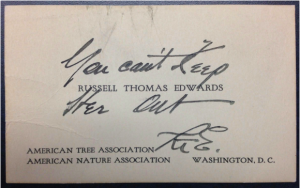

“You Can’t Keep Her Out”: Mary Church Terrell’s Fight for Equality in America

Project Group: Mickaela Fouad, Sarah Minion, Natalia Shevin

Student Editor: Natalia Shevin

Mary Eliza Church Terrell (1863-1954) was born in Memphis, Tennessee, to Robert Reed Church and Louisa Ayers, both mixed-race and formerly enslaved. Her father is widely known as the first Black millionaire in the South. Terrell sustained a commitment to social justice as well as to pioneering programs and developing opportunities for the advancement of both Black people and women.

After attending school in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Church enrolled in Oberlin College’s preparatory department from 1879 to 1880. Immediately following that, she spent four years in the college. While female students generally enrolled in the Literary Course, or “ladies’ course,” Mary Church chose to pursue the Classical Course, or “gentlemen’s course,” which required an additional two years and more rigorous study. Church graduated from Oberlin College in 1884, along with Anna Julia Haywood Cooper (1858-1964) and Ida Gibbs (1862-1957), who both remained lifelong colleagues.1 She excelled during her time at Oberlin College, receiving high marks in her classes and participating in a prestigious literary society.2

On 18 October 1891, Mary Church married Robert Heberton Terrell, the first Black man to graduate Magna Cum Laude from Harvard University. Mary Church Terrell suffered the loss of three children, with only Phyllis Church (later Langston) surviving past infancy.3 The Terrells adopted another child in 1905, Mary Louise (later Geaudreau). Both daughters attended Oberlin from 1913 to 1914; Phyllis enrolled in the academy and conservatory, and Mary Louise enrolled in the college.

Terrell sustained a lifelong relationship with Oberlin College, deeply moved by her own experiences and education, but later criticized its failure to uphold the values which she considered essential to its existence. She pushed for Oberlin to keep to its progressive roots to inform its pedagogy and residential policy. In 1911, to celebrate the centenary of the birth of Harriet Beecher Stowe, she hoped to give a lecture to Oberlin students about Stowe’s commitment to racial equality but was ultimately denied this opportunity. In 1914, the college refused to integrate housing for her daughters.

Despite this, she continued to cite her own time at Oberlin as a source of inspiration in her many years as an activist for diverse causes, including women’s issues, civil rights, and education. During her career she was the founding president of the National Association of Colored Women and founder of the College Alumnae Council. In addition, Terrell was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Women’s Committee for Equal Justice, the Civil Rights Congress, and the Women’s Republican League of Washington, D.C. She was the first Black woman to serve on the Washington D.C Board of Education.4

For a woman who worked closely with communists and accused communists later in life, she remained dedicated to the United States and its Constitution. She met regularly with politicians to demand justice for Black people and particularly Black women, once famously confronting William Howard Taft, then Secretary of War under Theodore Roosevelt, to investigate the dishonorable discharge of three Black soldiers in 1906. But her proximity to Washington did not keep her from participating in direct actions, particularly during her efforts to desegregate restaurants in the 1940s and 1950s.

While she championed countless causes, Terrell was especially active in support of the rights of Black women. She not only stood as an emblem of equality, but she also took up the cause of individual cases, such as that of Rosa Lee Ingram, who was falsely accused of murder. Fighting on the eve of the modern Civil Rights movement, Terrell used the newly established United Nations to challenge internal racist policies at a time when America sought to promote an image of democracy abroad. Ultimately, Mary Church Terrell’s fervor, persistence, and unwavering commitment to equality fueled her continued activism until her dying days.

The Oberlin College Archives holds an extensive collection for Mary Church Terrell, including her student files, correspondences with President Churchill King, and six new boxes that were donated by Terrell’s descendent in June 2015.

Note: For documents in this project, we have used “<>” to flag handwritten additions by the author to original typescripts.

1 Anna Julia Haywood Cooper (1858-1964) was a widow when she began at Oberlin College. Ida Gibbs (1862-1957; later Hunt). Terrell wrote in her diary on 26 March 1948 about a visit she had with Ida Gibbs Hunt, 64 years after attending Oberlin together.

2 Terrell was a member of the Aelioian Literary Society at Oberlin College.

3 Phyllis was named for Phyllis Wheatley, who was formerly enslaved and became the first Black woman poet to be published. On the 1905 Quinquennial Catalogue of Officers and Graduates, Terrell writes, “Children born: <Four children, of whom one only is living – Phyllis Church Terrell shall attend Oberlin College>” (Student File: Mary Church Terrell, Folder 2, O. C. A.).

4 She was not shy about reporting her achievements, especially to the Oberlin administration after they repeatedly ostracized her. In a letter to Oberlin College Secretary George Jones on 26 April 1935, Terrell informed him of her time as the Secretary of the Race Relations Committee of the Washington Federation of Churches, secretary of the Congregational Church, and appointment on the Board of Education. She wrote, “I tell you this, because it may interest you to know what an Oberlin woman does with her training when she works for the community in which she lives.” (Student File: Mary Church Terrell, Folder 2, O. C. A.).