The Oberlin Mutual Improvement Club 1913-1914

Project Group: Kyla VanGelder and Kathleen O’Connor

Student Editors: Rebecca Debus and Natalia Shevin

The Mutual Improvement Club was a social and political association formed by prominent Black women in the town of Oberlin, Ohio. The club,formed and federated on both the state and national level in 1913, was one of many Black women’s clubs established during the early twentieth century that became part of the National Association of Colored Women.[1] Many of the members of these clubs were educated Black Christian women who were very active in their churches and the community. Though they came from diverse backgrounds and social positions (elderly and young; married and single; working women and housewives, etc.), they came together with the common goal of improving themselves and their homes in order to uplift the race. Their motto “hand in hand, not one before the other” is a testament to this shared commitment and sense of collective ownership of civic life.[2] Like many comparable organizations from this time period, the Mutual Improvement Club walked the line between traditional studies of home economics and investigations into the role of Black women in fighting for racial justice.

The Mutual Improvement Club began its existence with an emphasis on home economics but gradually shifted to a more political focus during its second year. While to a modern reader, home economics may seem like an unlikely catalyst for more political discussion, as these Black Clubwomen were well aware, the home had always been a site of potential strength and subversion. As many members of the National Association of Colored Women believed, “to build the black home was to build the black nation.”[3] During their first year, the Mutual Improvement Club discussed such topics as “the influence of flowers in the home” and the “dangers and extermination of house fly.”[4] As the women came into contact with more clubs at state and national conventions, such as the eighth biennial convention of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs at Wilberforce, Ohio, in 1914, they began to focus more explicitly on race and positionality at their meetings.[5]

The National Association of Colored Women (NACW) was co-founded by prominent Black women including Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Margaret Washington, and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin.[6] The NACW promoted moral purity and temperance, and established Kindergartens and youth services. They organized from their position as Black women. Since, in their minds, “a race could rise no higher than its women,” they felt that when they improved the condition of black women, they necessarily improved the condition of the race.’”[7] They believed only they could speak on behalf of the race, given their centrality to the home and Black community. Many of the leaders of the NACW were educated and nationally acclaimed for their work, which they saw as part of their mission; “clubwomen wanted racial progress to be measured by their own success. In their estimation, they were their own best argument against discrimination.”[8]

Black women had, for many years, participated in group organizations dedicated to Christian charity. Their allusions to biblical texts and their close ties to local churches and Christian organizations suggest that the women of the Mutual Improvement Club would have been united by their faith and sense of Christian moral duty. The first year of the club’s activity included two lectures by local ministers on how the women in the club could improve their communities. In its first year, the club was fairly traditional, and for the most part stayed true to its projected study of home economics. While they did touch on education and opportunities for civic improvement, the subject matter remained mostly domestic and well within the realm of respected civic engagement for black women.

The Mutual Improvement Club may have formed as a female counterpart to the Colored Law and Order League of Oberlin, a men’s organization with similar goals. Many of the women’s husbands, including J.S. Burton (President), T.A. Bows, E.W. Mitchell, and J.A. Berry (Secretary) were active in the formation of this organization in 1908. “Inasmuch as it has been a national cry of blaming the entire colored race for the immorality and crimes of a few, it was determined to take a firm stand for purity of private life and sanctity of the home, honesty of the purpose and strictest morality of character, and then all colored men must take a stand with or against this organization.” They opposed “drunkenness and debauchery,” rhetorically aligning themselves with the temperance movement of the time. The men saw the role of women as limited, perhaps reflecting the class demographic of the organization.[9]

The Oberlin College Archives holds no information on the Mutual Improvement Club after 1915,, which suggests that it may have disbanded. However, several women involved in the club, including Mary Murphy, continued on in Black woman’s club work as part of the Oberlin Council for Colored Women, which was organized in 1916.[10]

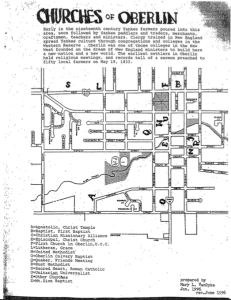

Despite the sparseness of the Mutual Improvement Club’s records, they do offer aunique insight into Black women’s clubs. The women of the Mutual Improvement Club were linked not only by their interests in politics and home economics, but were often directly related to each other. They attended the same schools, worshiped at the same churches, and read the same papers. The Mutual Improvement Club simply tapped into a network of Black women that already existed, and probably encompassed greater economic and social diversity than was common in white women’s clubs, which were almost exclusively aimed at educated housewives rather than working women. The Mutual Improvement Club’s focus on matters relating to both the home and politics reflects the ways in which racial uplift was tied to the traditional woman’s sphere. It also highlights the intersectionality of racial equality and women’s equality whichshaped the activism of many Black women throughout the twentieth century.

This project relies upon two yearbooks issued by the Mutual Improvement Club, the first for 1913-1914 , and the second for 1914-1915. The yearbooks are pocket-sized with blue covers, possibly to reflect the colors of the club. These yearbooks are the only items found in the Oberlin College Archives for the Mutual Improvement Club. They record the concerns of this small-town Black women’s club during the early twentieth century. We see in this yearbook an emphasis on the woman’s place in the home and the respectability of the home as a vessel for greater importance and empowerment as Black women.

[1] Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894-1994, 1st ed, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 27.

[2] Their motto is a quote from Act 5, Scene 1 of The Comedy of Errors, by William Shakespeare.

[3] Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load, 45.

[4] Mutual Improvement Club, 1913-1915, RG 31/6/14. O.C.A.

[5] Daphne Spain, How Women Saved the City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 83.

[6] National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, “Who we are,” 2011, Web address, accessed 19 August 2015.

[7] Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load, 24.

[8] Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load, 53.

[9] “Colored Citizens Organize: Determined to Preserve Order and to Weed Out Undesirable Element,”Oberlin News, 23 September 1908, page 2.

[10] “Mothers to Organize for Civic Betterment: Oberlin Council of Colored Women to Be Formed Here Soon,” Oberlin News, 5 April 1916.