Document 1: 21 August 1917, Ruth Alexander to Herman Nichols | Document 2: 23 August 1918, Albert Britt to Ruth Alexander

Document 3: 1919 Thomas Clay O’Donnell to Ruth Alexander | Document 4: 23 May 1927 Jean M. Whitman to Ruth Nichols

Document 5: 20 June 1931- W. C. Vogt to Ruth Nichols | Document 6 & 7 Introduction

Document 6: 14 June 1950, W.H. Zippler to Ruth Nichols | Document 7: 20 June 1950, Ruth Nichols to W.H. Zippler

Document 8: 1953 – Better Homes and Gardens Transcript | Bibliography

Project Group: Laura Feyer, Willa Kerkhoff, and Nora Rice

Student Editor: Rebecca Debus

Introduction:

Source: Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.

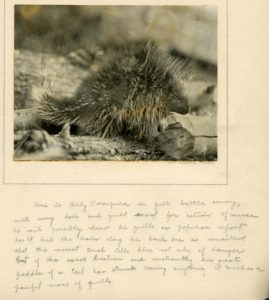

Ruth Edla Alexander was born on 30 September 1893, in Bethany, Nebraska, to Dr. Benjamin Johnson Alexander and Ida May Smith Alexander. Several years later the family moved to Hiawatha, Kansas, where Alexander spent most of her childhood and young adulthood[1] Alexander attended Oberlin College, graduating with an A.B. in 1915. That year she also published her first short story, which featured a squirrel, in the magazine Little Folks.[2] After graduation, she moved home, possibly to help her father, who died after an illness in 1917. While still at home in 1916, Alexander began to work as a second grade teacher.[3] Then from 1917 to 1918 she lived in Manhattan, Kansas, where she joined the war effort as a club leader in the YWCA and the War Camp Community Service. In the fall of 1919 she moved to New York, where she found work as a writer and photographer for the publicity firm of Tamblyn and Brown.[4] Her work primarily consisted of visiting college campuses and crafting brochures for them. These brochures were entirely Alexander’s own work; she did all the photography and writing. It seems she continued working with the firm until 1923 when she moved to Westfield, New Jersey, with her husband. Ruth Alexander married her Oberlin classmate Herman Nichols on 23 October 1920.[5] The two had been dating for at least three years, and had maintained a long romantic correspondence after graduation, particularly while Herman was serving in World War I. The couple had two children together, Jane Ellis Nichols, born on28 April 1922, and Anne Townsend Nichols, born 23 April 1924, three months after Herman’s death in early February of the same year.[6]

Since her first published story in 1915, Ruth Nichols had continued to sell not only stories but photographs, to various publications. After she was widowed, she focused intently on her photography and soon reached a level of success where she was able to support herself and her daughters through her work. Though her initial work dealt mostly with nature photography, her career took off after she began to sell portraits of her daughters to publishing houses.[7] These photos, unlike many of children at the time, showed her daughters in natural lighting and poses. This lack of stiff models appealed greatly to parents, consumer, and advertisers,

Source: Series XIII. Photographs, Box 12. Nichols Family Papers, RG 30/372. O.C.A.

and by 1925 Nichols made her name as a photographer of children.[8] As the 1930s began and the Great Depression took its economic toll, Nichols was on her way to setting up her own business. Despite the hardships suffered by many single women of this time, she saw great success as a photographer and author, particularly after her work came to the attention of advertising firms, who began to employ her regularly.[9] It was during these years that she also became known for her use of Cabro prints. This color printing technique had extremely long development times, but resulted in highly detailed prints.[10] Due to both expense and difficulty, it was not much in use at the time, which gave Nichols’ prints a competitive edge over those of other photographers.

At some point, possibly in 1935,[11] Ruth Nichols married her second husband, Brewster Sperry Beach, a war veteran and advertiser. Though she took his last name for her social purposes, as was customary at the time, she remained Ruth Nichols professionally. They remained together until Ruth Nichols’ death on 2 April 1970.

In the 1940s Nichols resisted the call for women to enter the wartime industrial workforce and instead continued to grow her own independent business. As a result, after the war ended, Ruth was able to continue her work and dodge the fate of other women, who were forced out of their newfound workplaces by returning veterans.[12] By the 1950s she was a seasoned and clever business woman, still making her money by capturing idyllic images of blonde, white babies and their blithely smiling mothers. Many of those images were used in advertisements that found their way into magazines like Better Homes and Gardens. These magazines, and Nichols’ ads for them, painted a very specific vision of what motherhood and family life were supposed to look like in the United States in the post-war world: a nuclear middle-class home in the suburbs, with a successful father, and a pretty wife who stayed at home with her well-dressed children and impeccable house. The success of these magazines influenced the world views and desires of married middle-to-upper-class white women of the time, and led to many of the problematic viewpoints described by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique.[13] Ironically, even as Nichols had a successful professional career herself, her work contributed to the prevailing viewpoint that a woman’s place was in the home with her children. Though the success of Nichols herself challenges the assumptions that women in the interwar period remained in the home, the success of her photographs underscores the very prevalence of this viewpoint. This dichotomy reflects some of the difficulties faced by early Second Wave feminists, who could often succeed in defying the patriarchy themselves, but sometimes still contributed to patriarchal systems or merely served as an exception to the rule.

Source: Series XIII. Photographs, Box 12. Nichols Family Papers, RG 30/372. O.C.A.

This mini-edition project chronicles Nichols’ transformation from a young and enthusiastic amateur into an experienced entrepreneur, capable of weathering the various unique challenges faced by a single woman running a business during this time period. The documents transcribed here span the period 1917 -1953, and illustrate Nichols’ long journey from hobbyist to professional. They range from letters to her husband about her early endeavours in nature photography, to correspondence from publishers accepting her work into their magazines, to letters from admirers praising her photographs. The early documents focus on her pursuit of nature photography and short story writing. However, later documents show that as she was forced to consider not just her art but also her finances, her work gradually shifted into a focus on her photography of babies and children.[14] Overall, these documents illustrate the growing business acumen of Ruth Alexander Nichols in a time when American culture did not encourage female entrepreneurs. Though Ruth Nichols’ photographs may have played into the image of female domesticity that was being carefully crafted during this time, her talent, her business sense, and her persistence, allowed her to thrive as well-known professional photographer, defying the

Source: Series IX. Scrapbooks, Box 1. Nichols Family Papers, RG 30/372. O.C.A.

oppressive systems that would have relegated her to the domestic sphere.

[1] Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.

[2] Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.; Finding Guide, Nichols Family Papers (1884-1962), Record Group 30/372, O.C.A. web link.

[3] Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.

[4] Tamblyn and Brown was officially formed in 1920, but the two founders, George Tamblyn and John Crosby Brown, had worked together for about two years prior. They were a campaigning organization, dedicated to raising funds and awareness for specific endeavours. They focused heavily on the publicity aspect of fundraising, which is likely where photographers like Alexander came in handy (Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.; Scott M. Cutlip. Fund Raising in the United States: Its Role in America’s Philanthropy. (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1965) 165-166.)

[5] Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.

[6] Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.

[9] Meridel LeSueur, Harvest: Collected Stories (West End Press, 1977), 21-28.; Finding Guide, Nichols Family Papers (1884-1962), Record Group 30/372, O.C.A. web link.

[11] The details of Nichols’ marriage to Beach are uncertain. While her daughter reported later that they married in 1935, no official records of their marriage could be found, and in 1930, Brewster Sperry Beach was still married to Orlena Weed Beach, with whom he had two children, Kelsey and Brewster Jr. Orlena did not die until 1976, and was still communicating with Brewster Beach into at least the 1940s. No divorce record for them could be found (“California, Death Index, 1940-1997 – AncestryLibrary.com.” Accessed 22 June 2016. Web link.; Student File, Ruth Alexander Nichols, Record Group 28/2, Box 57, O.C.A.; Finding Guide, Nichols Family Papers (1884-1962), Record Group 30/372, O.C.A. web link).

[12] Dorothy Sue Cobble, “When Feminism had Class” in What’s Class Got To Do With It?, ed. Michael Zweig (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press), 23-34.

[13] The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963, is considered by many to be one of the germinal works of the second wave. Describing the plight of suburban housewives, the book struck a chord with many women, and led to a popularization of the feminist movement (then often called “Women’s Liberation” or Women’s Lib). While Friedan’s work addressed the problems of a very specific group of women and didn’t necessarily address the concerns of many women, including women of color, poorer women, and LGBTQ women, her work did cause the mobilization of those suburban housewives, and helped bring both numbers and visibility into the fight equal rights and social equality (Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1963).).