|

|

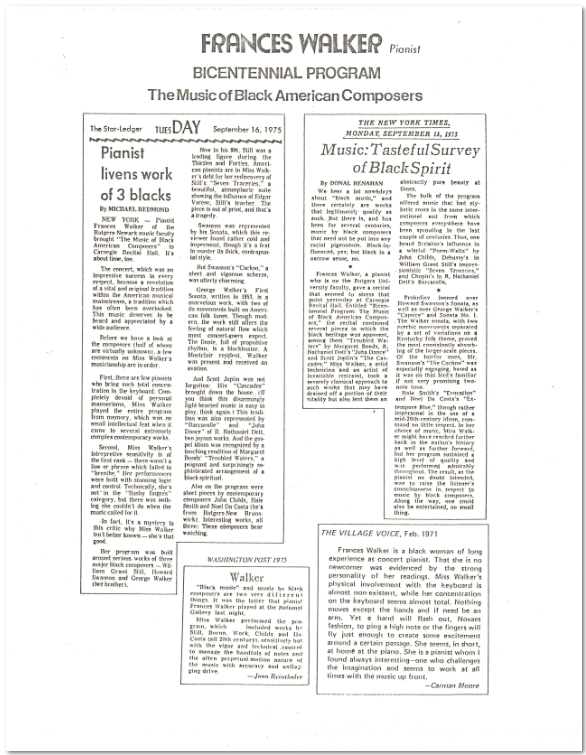

Transcription: THE NEW YORK TIMES, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 1975 Music: Tasteful Survey of Black Spirit By DONAL HENAHAN We hear a lot nowadays about “black music,” and there certainly are works that legitimately qualify as such. But there is, and has been for several centuries, music by black composers that need not be put into any racial pigeonhole. Black-influenced, yes; but black in a narrow sense, no.[3] Frances Walker, a pianist who is on the Rutgers University faculty, gave a recital that seemed to stress that point yesterday at Carnegie Recital Hall. Entitled “Bicentennial Program: The Music of Black American Composers,” the recital contained several pieces in which the black heritage was apparent, among them “Troubled Waters”[4] by Margaret Bonds, R. Nathaniel Dett’s “Juba Dance” and Scott Joplin’s “The Cascades.” Miss Walker, a solid technician and an artist of invariable restraint, took a severely classical approach to such works that may have drained off a portion of their vitality but also lent them an abstractly pure beauty at times. The bulk of the program offered music that had stylistic roots in the same international soil from which composers everywhere have been sprouting in the last couple of centuries. Thus, one heard Scriabin’s influence in a wistful “Poem-Waltz” by John Childs, Debussy’s in William Grant Still’s impressionistic “Seven Traceries,” and Chopin’s in R. Nathaniel Dett’s Barcarolle. Prokofiev loomed over Howard Swanson’s Sonata, as well as over George Walker’s “Caprice” and Sonata No. 1. The Walker sonata, with two acerbic movements separated by a set of variations on a Kentucky folk theme, proved the most consistently absorbing of the larger-scale pieces. Of the briefer ones, Mr. Swanson’s “The Cuckoo”[5] was especially engaging, based as it was on that bird’s familiar if not very promising two-note tune. Hale Smith’s “Evocation” and Noel Da Costa’s “Extempore Blue,” though rather impersonal in the use of a mid-20th-century idiom, command no little respect. In her choice of music, Miss Walker might have reached further back in the nation’s history as well as further forward, but her program sustained a high level of quality and was performed admirably throughout. The result, as the pianist no doubt intended, was to raise the listener’s consciousness in respect to music by black composers. Along the way, one could also be entertained, no small thing. |

[1] In another article written by Henahan in 1972, he praised The New York Philharmonic’s agreement to fair-employment practices. He wrote about the event as a “seismic rumbling [that] can only lift the hopes of those of us who have listened in growing consternation while spokesmen both black and white have advised us that the country’s only future lies in some homegrown variety of apartheid.” Later on in this article, Henahan recognized the burden that Black musicians faced: “With so brief a history of symphonic participation, the black today finds himself constantly on the defensive and forced, like the Jew of previous centuries who was locked inside the Pale, to be twice as good in order to succeed.” On the other hand, William Grant Still sometimes wrote against this sentiment.In his 1937 essay, “Are Negro Composers Handicapped?” he asserted: “the colored man is handicapped solely by the extent of his own capacity-or his lack of capacity-for advancement.” Still wrote extensively throughout his career, and perhaps later changed his mind (Donal Henahan, “An About Face on Black Musicians at The Philharmonic,” The New York Times, 11 June 1972, Source, accessed 14 July 2016; William Grant Still, “Are Negro Musicians Handicapped?” The Baton I, No. 2 (November 1937): 3, in The William Grant Still Reader: Essays on American Music, ed. Jon Michael Spencer, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Durham: Duke University Press, Fall 1992), 88.

[2] Frances Walker-Slocum, A Miraculous Life (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2006), 137.

[3] Joan Reinthaler, a music critic for The Washington Post, reiterated Henahan’s idea in her review of the Bicentennial Program. She wrote, “‘Black music’ and music by black composers are two very different things. It was the latter that pianist Frances Walker played at the National Gallery last night. Miss Walker performed the program, which included works by Still, Bornn, Work, Childs and Da Costa (all 20th century), sensitively but with the vigor and technical control to manage the handfuls of notes and the often perpetual-motion nature of the music with accuracy and unflagging drive” (“Frances Walker Bicentennial Program: The Music of Black American Composers” Bicentennial Program; Folder: 1950s-1990s; Series: III Clippings; Frances Walker-Slocum; Record Group: Frances Walker-Slocum Papers; Box 1; O. C. A.).

[4] “Troubled Waters” is an adaptation of the traditional Black spiritual, “Wade in the Water.” Louise Toppin, an opera singer and voice professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill spoke about Bonds’ adaptation of “Troubled Water”: “you have to have a feel for jazz to play that piece, but you also get a good sense of what a fine pianist Margaret Bonds had to have been to play that” (Celeste Headlee, “At 100, Composer Margaret Bonds Remains A Great Exception,” National Public Radio, source, accessed 14 July 2016).

[5] Walker-Slocum frequently performed Howard Swanson’s piece, “Cuckoo,” which piece is known for its perpetual cuckoo motif in the left hand. It is usually a short, humorous encore.