Document 1

Author: Dan Bradley

Title: Adelia Antoinette Field Johnston: An Appreciation.

Date: October 1936

Location: Adelia A. Field Johnston Papers, Series I. Biographical File,

Document Type: Printed Document

Introduction:

Dan Freeman Bradley was born on 17 March 1857 in what was then Bangkok, Siam, to missionary parents, Rev. Dan Beach Bradley and Sarah Blachly Bradley.1 His father’s missionary work, which included establishing print shops and western hospitals in Siam, brought him into contact with many notables of the country, including the King. The young Dan Bradley distinguished himself early on by working for his father’s print shop, the first of its kind in the country.2 His mother, Sarah Bradley, was one of the first women to receive a degree from Oberlin College, and she sent many of her children to Oberlin to study. As Dan notes, at least five of them, including himself, were taught by Adelia Field Johnston.

Dan Bradley received his A.B. from Oberlin College, and then attended the theological seminary, where he received his B.D. and D.D., graduating in 1885.3 In 1883 he married fellow Oberlin classmate Lillian Josephine Jacques (d. 1937), with whom he had three sons who lived to adulthood, all of whom studied at Oberlin.4 After his graduation, Bradley served as a pastor for various churches, and was President of the Protestant Church Federation, but also held many distinguished secular jobs. He served as the President of both Yankton and Grinnell Colleges, Director of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce and as a member of the Oberlin Board of Trustees.5 He was also a well-known temperance advocate, and often used his various positions to further that cause. He died on 12 November 1939.6

His close ties to Oberlin kept him in contact with Adelia Field Johnston, and the two seem to have been good friends, as there are newspaper clippings that show her visiting him and his family in Cleveland.7 This particularly close relationship with Johnston doubtlessly made him the obvious choice to write a eulogy for her in the Alumni magazine.

This eulogy, part of which is transcribed below, gives a detailed summary of Johnston’s life and her contributions to Oberlin, and underscores how important she was to the development of the college during the later portion of the nineteenth century. Of special interest is the discussion of Johnston’s fundraising abilities in the ninth paragraph; Oberlin students may be interested to learn how many of the buildings currently on campus Johnston made possible. Also of note is Bradley’s mention of Johnston’s strict disciplinary measures, particularly regarding the interaction of the sexes. Despite, or perhaps because of, Oberlin’s growing reputation, Johnston clearly felt responsible in her position as Dean of Women, for maintaining the college’s moral image in the face of critics, who commonly insinuated that co-education promoted licentious behavior.

The eulogy also reveals just how magnetic and compelling a person Johnston was. Her many students, Dan Bradley included, seem to have adored her, and much of her fundraising ability seemed to come from this magnetism. In addition to the examples Bradley mentions below, Johnston was also able to obtain money to build a women’s skating rink, when she just happened to run into the entrepreneur and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller on the streets of New York.8 Her force of personality also made her professorship at Oberlin possible; she only began to teach outside the Ladies’ Department because male students were requesting entrance into her classes.9 Though she never officially undertook PhD. studies, her skill as a teacher resulted in the Oberlin faculty awarding her both her degree and her Professorship in 1890. Throughout this memorial, Bradley gave a remarkable insight into the character of this fascinating woman.

(Note: though this document appears first in this edition, as it offers a detailed biography of Johnston’s life and provides context for many of the other documents, it was actually written last, in 1936, many years after Johnston’s death in 1911.)

Transcription:

Adelia Antoinette Field Johnston

An Appreciation

By Dr. Dan F. Bradley

In the autumn of 1877, I found myself a lad of twenty, entering the Preparatory Department10 of Oberlin College, then under the guidance of Principal George H. White,11 who had been installed the year before, and was attracting attention as an Eastern12 man of sterling scholarship and vivid personality. I was so backward in my studies that it became necessary for me to be placed in classes in English Grammar, in Advanced Arithmetic, and beginning Latin. Principal White who assigned me, suggested that I add Science of Government. It was a heavy schedule for one who had never before been in a schoolroom, but I was in a hurry to get on. The class in Science of Government was very large and occupied the largest room in French Hall. As I went up in line to show my assignment, I faced an amazingly interesting woman of forty—with thin lips, alert eyes, who stood to receive us. When she saw my name, her stern, serious attitude instantly changed into an attractive smile, and she greeted me as the most recent member of a family—of which four had been in her classes. That half-a-minute interview insured my standing and immunity from all the hazards of eight years in Oberlin. Adelia Antoinette Field Johnston was the teacher of that class, which under her brilliant leadership became a picnic. Nobody could afford to be absent. Government, especially the government of the United States, under the Constitution, became a thrilling story. Before the term ended, the whole class of fifty had committed to memory the Preamble, the Constitution, the Amendments and the Bill of Rights, and at the concluding session, we spelled down on each Article and Amendment.

In her charming biography, Miss Harriet Keeler13 calls Mrs. Johnston a great teacher. There was no question of it in any of her classes. It was my privilege to be in her class in botany two years later, and there again the bright hour of the day was the one when trees and shrubs and the little spring plants that come to light and pass away in May, the adder-tongue,14 the anemone,15 the hepatica16 became the firm friends of us, all through the years. To me, who had lived all my life in the lush tropics,17 the exquisite flora of Northern Ohio, became an artistic creation under the leadership of this wonderful woman. And who of us can ever forget those May excursions to the gorges of Black River in Elyria where in the 70’s nature had achieved her utmost?

Mrs. Johnston possessed an independent mind, and her early training as a farmer’s daughter, moving from Medina County to Geauga and Huron counties, and finally upon her father’s death, settling with her mother and sister in Oberlin, gave the precocious little girl a quality that marked her whole stirring life. Her father was her first and best teacher. At thirteen she substituted for a sick teacher in the country school. At fifteen she became a member of the Ladies’ Course at Oberlin.18 Meantime her alert mind seized and grasped everything in sight, and what she could not see and hear she instinctively and accurately imagined.

Graduating at nineteen, she taught in a girl’s school at Mossy Creek in Tennessee,19 and while there she experienced the isolation of one who had to conceal the fact that she had been in Oberlin because of its record on slavery.20 Her letters could not be mailed from there to Oberlin lest she should be dismissed in disgrace.21 In 1859, when she was twenty-two, she returned to Ohio and married the man to whom she had been engaged in College days-James M. Johnston,22 then Principal of the Orwell School at Orwell, Ohio.23 She assisted in the school and the two pursued advanced studies together

…

At thirty-three she was offered the Principalship of the Ladies’ Department and served the young women of Oberlin as Principal for thirty years, then as Dean of Women.24

To them she gave her best, as teacher of history25 and as lecturer in the General Exercises26 which were events rather than appointments, for there the whole wealth of her experience and culture was conveyed to the young women in eloquent language and with passionate earnestness. There were things to shun, there were great things to reach for and gain, there was the cultivating of tact. Womanhood was God’s special gift, to be reverenced and devoted to noble services. Hundreds of the finest women of America have responded to the charm and eloquence of her appeal to young womanhood.

There were those who thought Mrs. Johnston unnecessarily strict and severe in College discipline. It is hard for College youth to be denied a longed-for expression of friendship in a walk, or a chat in the dark, with a congenial comrade. But the rule in Oberlin was that a girl must not walk with a man from church or choir “unless they were going the same way” (sic).27 Some rules are easily misunderstood.28 But Oberlin was an experiment in co-education and its enemies were watching for its failures, and careful, discreet management that today would be deemed extreme by conservatives, was exceedingly necessary.

Mrs. Johnston’s service to Oberlin College was significant in the steadily increasing influence she exerted in the Faculty. Her’s was a liberal mind, progressive, and in the years of her Deanship, the status of education for women was made increasingly advanced from their rather inferior place to that of equality in every respect with the liberal arts student.29 And this was accomplished through her personal influence that was made to bear upon questions not in a way of antagonism to the status quo, [sic] but in the way of insistent sensible counsel. The men and women with whom she worked were rare scholars and persons of unusual capacity. There were James H. Fairchild,30 John Ellis,31 Fenelon B. Rice,32 Henry King33 and many others, but among them all she was prima inter pares [sic]34

It was sometimes said of her that she had her favorites.35 It may be true, but if so it was due to her instinctive appreciation of values in people. She liked people that were not drab or commonplace, but had outstanding interesting values. Thus her special acquaintances like the Rice’s, the Warner’s,36 the Baldwin’s,37 were people of distinction and friends of the causes she loved.

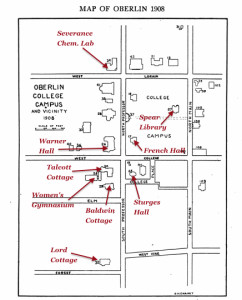

It is interesting to know that many of the buildings that were added to the College equipment came from people who were drawn to her, and with whom she became a skillful salesman for Oberlin. Baldwin38 and Talcott39 cottages, Sturges Hall, the Warner Musical building, Spear Library, Lord Cottage,40 were the result of her activity in making donors feel the pleasure of giving this equipment. Through Mrs. Johnston the Severance family first became interested in Oberlin. Because of her, Dr. Dudley P. Allen41 moved to Oberlin; his son, Dr. Dudley P. Allen subsequently married the daughter of Mr. Louis H. Severance who gave the Severance Chemical Laboratory and endowed the chair of Chemistry and Mineralogy. As a memorial the Dudley Peter Allen Art Museum with its generous endowment was given by her for the enrichment of the cultural and esthetic [sic] life of the community.

Mrs. Johnston continued to enlarge her horizon and cultivate her imagination by travel at home and abroad,42 and her lectures were made vivid by her observation of Cathedrals and Monasteries in England and Europe,43 of tombs and pyramids in Egypt. When the time came for her retirement, she continued her interest in making Oberlin beautiful.44 The banks of the sluggish Plumb Creek45 were made to add grace and dignity to the Community Parkway46 that traversed the town from West to East, from the Arboretum47 which she made possible, to the beautiful lands on the East.

So lived this woman of singular charm and of superb character, who used all of her gifts for the blessing and beauty of the world which she knew and loved. In the story of Oberlin now beginning its second century, there is no woman more beloved, and for whom there should be greater gratitude on the part of our alumni than Adelia Antoinette Field Johnston.

Reprint from Oberlin Alumni Magazine for October, 1936 [sic].

Transcribed by Taylor Swift.

1Siam is an older name for the country of Thailand.

2The elder Dan Bradley was the first person to render the Siamese script into types for printing (Former Student File, Bradley, Dan Freeman. Box 99. Oberlin College Archives).

3Bachelor of Divinity and Doctor of Divinity.

4Lillian Jaques was also a teacher at the Oberlin Conservatory (Former Student File, Bradley, Dan Freeman. Box 99. Oberlin College Archives).

5Former Student File, Bradley, Dan Freeman. Box 99. Oberlin College Archives.

6Former Student File, Bradley, Dan Freeman. Box 99. Oberlin College Archives.

7Former Student File, Johnston, Adelia A.F. Box 539. Oberlin College Archives.

8Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston Who Served Oberlin College for Thirty-Seven Years … Britton Printing Company, 1912. Memorial Record of the County of Cuyahoga and City of Cleveland, Ohio. Genealogical Committee, Western Reserve Historical Society, 1894.

9Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston

10Though it is no longer in existence, Oberlin College used to have a Preparatory Department that was meant for those students either too young, or in need of remedial work, to enter the college proper.

11Though it is no longer in existence, Oberlin College used to have a Preparatory Department that was meant for those students either too young, or in need of remedial work, to enter the college proper.

12 Eastern here refers to the East Coast of the United States; White was from Massachusetts and had attended Amherst College (The Oberlin News, 12 October 1893).

13 Harriet Keeler (1846-1921), graduated from Oberlin College in 1870 and became the first female Superintendent of Schools in Cleveland, Ohio. She wrote a biography of Johnston entitled The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston, which was published in 1912, and includes both the results of Keeler’s own research, as well as a short autobiography written by Johnston herself, and excerpts from her diary and various travel accounts. Keeler was quite close to Johnston, and the two of them traveled together on several occasions ( Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston; Former Student File, Johnston, Adelia A.F. Box 539. Oberlin College Archives).

14A type of lily that grows in temperate forests and meadows.

15A genus of flowers, though it is unclear which type within the genus Bradley is referring to.

16 A type of small flower; the varieties growing today in Oberlin are predominantly purple.

17Bradley grew up in Siam, which was the former name of the country of Thailand.

18 Although Oberlin opened classes to both sexes in 1833, the majority of female students in the early years of the college did not enter into the Classical Course, which granted an A.B. Instead, they took the Ladies’ Course, which offered a diploma but no degree. When Adelia Field attended the college, women had already graduated from the Classical Course, but Field’s mother and the current Ladies’ Principal, Marianne P. Dascomb, dissuaded her from pursuing a degree herself. Johnston later stated that she always regretted this, and studied on her own the subjects that would have allowed her to obtain an A.B. through the Classical Course (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

19The school in question was the newly created Black Oak Grove Seminary; it was meant to educate the local young women, without them having to be sent so far from home. Adelia Field obtained her post as Principal of the school when a friend of one of the founders heard her graduation speech at Oberlin (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston; Former Student File, Johnston, Adelia A.F. Box 539. Oberlin College Archives).

20Oberlin was considered a hotbed of abolitionism in the South, both for the town’s involvement in the Underground Railroad and open opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act, and for the College’s decision to admit students of color alongside white students. Both the school and the town were well known at the time. See Nat Brandt’s book, The Town that Started the Civil War, for more details on Oberlin’s role in the abolitionist movement.

21She had something of a close call, when her impatient fiance, James Johnston, decided to mail several letters directly to her from Oberlin. The postmaster of Mossy Creek was a defiantly pro-slavery southerner, and he confronted Adelia Field about her association with Oberlin at a party. A recounting of this incident was published in a newspaper in Grand, Rapids, Michigan, The Democrat, on 3 January 1897, when Johnston was in the area visiting Dan Bradley and his wife. The account reads: [The Postmaster] stationed himself as remote from her as the room would permit and at a time when he might be heard the most distinctly he called out in a voice which attracted the attention of the entire company: “Say, Miss Field, did you ever hear of Oberlin?” Dean Johnston says she was sure that he intended to make a sensation by announcing that she was from Oberlin College and that probably she was there in Mossy Creek in the secret capacity of a Northern Spy. Spurred on by fear of sudden banishment, if not imprisonment, she quickly collected herself and answered briskly: “Oh certainly, I am familiar with the history of Oberlin. Without giving her inquisitor time to interrupt she gave a glowing account of the life of Pastor Oberlin and his wonderful work among the peasants of Alsace and Lorraine. “He was the most interesting man I ever heard of” she added and at the request of several standing near she gave a detailed description of his manner of teaching the French peasants and his religious labours among them. The man was not to be baffled in this strategic manner and so as soon as the story of the French philanthropist was ended he said to her: “I do not mean a man by the name of Oberlin but a place. Do you not know of a town by that name?” Miss Field waited a moment as though trying to recall to her memory some place bearing the name of Oberlin and answered: “It is possible I do, as Americans are always naming places after distinguished men. Now there are a good many Washingtons, Jeffersons, and Jacksons in our country and I dare to say there may be several towns named in honor of the great man Oberlin.” The postmaster became nettled and lost his self possession. In a loud accusing voice and while glaring fiercely at her, he demanded: “Do you not know of a town by that name in the North from where you came?” The man had reserved this question for his masterpiece with which he evidently intended to efface the young lady. She looked at him with perfect composure and replied“Oh, yes. I do remember a little town by that name in Ohio. I now recollect being in the place and I have a friend who has been visiting there.” This answer was unexpected and the postmaster to all intents decided within himself that he had been misled in his suspicions.” (Former Student File, Johnston, Adelia A.F. Box 539. Oberlin College Archives; Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston)

22James M. Johnston, (1833-1862), met Adelia Field while the two were students together at Oberlin and the two became engaged. While Field went to teach in Mossy Creek, Tennessee, after she graduated, Johnston remained at Oberlin. Upon his graduation three years later, the two married, and taught together at the Orwell Academy. When the Civil War broke out, James resigned his post and enlisted in the Army; Adelia also resigned her teaching position and became a nurse at a base near where he was stationed. Soon after he joined the army, James caught a severe cold, and died from complications relating to it. He and Adelia had been married less than three years. According to her biography, Adelia was severely depressed by his death, and supposedly only found the strength to continue living after she had a vision of James who told her that she must go one living, for “there was much in the world for her to do.” Whatever the source of this vision, it seems to have given Johnston a great deal of hope and strengthened her faith; several of her students said that she related this story to them in order to comfort them in their own grief (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

23 The Orwell School was a semi-private academy founded in 1855, and was affiliated at various points with the free-soiler movement, which Johnston had supported (Michael Zakim, “Antislavery and a Modern America: Free Soil in Ashtabula County, Ohio, 1848,” Oberlin College History Department Honors Thesis, 1981.; C.M. Thompson, “OHIO GENEALOGY EXPRESS – Lake County, Ohio – Biographies.” Ohio Genealogy Express. web address, accessed 10 July 2015).

24She was Principal and Dean for thirty years total: they were simply two different titles for the same position.

25Johnston taught many classes during her time at Oberlin; she was awarded the title of Professor of Medieval History, and seems to have been most interested in historical subjects.

26The General Exercises were lectures given by Johnston (in her capacity as the Dean of Women) every two weeks to the female student body. These lectures covered a variety of subjects, and were intended to aid the young women as they prepared to enter the wider world, either as wives, mothers, or professionals in their own right. Many of her former students remembered these lectures vividly and they seem to have made a great impression on the whole of the female student body (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

27This [sic] is in the original text of the memorial article by Dan Bradley and was not added by the transcriber.

28Johnston’s strictness surrounding rules and the potential interactions of the genders was apparently a well-known facet of her deanship, and one often commented on, though it does not seemed to have greatly diminished the admiration that many students felt for her.

29Under Adelia Field Johnston’s eye, not only did the students of the Ladies Department seeming obtain more respect and resources, but the curriculum and the designation of the Course itself was changed. One of the biggest difference between the Ladies Course and the regular College Course that led to a degree, known as the Classical Course, was that the Classical Course required that students learn Greek. While Johnston was at Oberlin, a third course was established, called the Philosophical Course, which also offered a degree, but did not require that students learn Greek. Though the Ladies Course never offered a degree, the name was changed to the Literary Course, and all gendered references to it were removed from the course catalogue. These changes had the effect of making Oberlin more openly accepting of women obtaining degrees, and helped to remove the notion that women were somehow all pursuing a lesser or easier course of higher education (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

30 James Harris Fairchild (1817-1902), was born in Lorain County and attended Oberlin during the early years of the school’s existence. He became a tutor and professor in various subjects at Oberlin College in 1839, and then was appointed as the third President of the College in 1866. He served as President for 23 years. See the Kellogg-Fairchild Letters for more details. (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

31John Millott Ellis (1831-1894), was an a staunch abolitionist and professor of Philosophy at Oberlin College from 1866 to 1896. He served as acting President in 1871.

32Fenelon B. Rice (1841-1901), who was a good friend of Johnston’s, was one of the founders of the Oberlin Conservatory, and served as director for 31 years. Rice Hall was built in 1910 in his honor.

33 Henry Churchill King (1858-1934), served as President of Oberlin from 1902 to 1927.

34 Prima inter pares is latin for “first among equals”.

35 Bradley was clearly one of those favorites. As he mentions here, she was apparently closely acquainted with several of his family members. Johnston also mentions his mother in an essay she wrote refuting the notion that co-education is detrimental to women, part of which is excerpted in this collection. As the part that mentions Mrs. Bradley is not included in the transcription, it is related here: “If Mrs. Bradley, who years ago went to Siam, and, besides her numerous public duties as a missionary, has found time to carry on the education of her own children, sending back her sons, one of them, at least, fully fitted for college, and now that her husband has been taken from her by death, still hopefully continues in the work….- are masculine women, the world- humanity says, Give us more such women.” (Oberlin College Archives, Adelia A. Field Johnston Papers. Series IV Writings and Notebooks, 1862-1994 (span). RG 30/19).

36 Dr. Lucien Calvin Warner (1842-1925), a physician, factory owner, and founder of the Warner Chemical Company, and his wife Karen Warner (b. 1850) were good friends of Johnston throughout much of her life, and were responsible for the donations that made Warner Music Hall possible; they also appear to have been friends with the Baldwins (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston, 130; “Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929 – AncestryLibrary.com.” Ancestry.com. web address, accessed 29 July 2015).

37 In December of 1880, Johnston suffered from a severe attack of pneumonia, and nearly died. Under Dr. Allen’s advice, she went south, to Nassau (the capital of the Bahamas) and Florida, for the rest of the winter and spring. While in Florida, she stayed at boarding house called Rose Cottage and there made the acquaintance of Elbert Irving Baldwin (1829-1894) and Mary Baldwin, formerly Miss Mary Jeannette Sterling. The Baldwins soon became close friends of Johnston, and they traveled to Europe together in the fall of 1881. Through Johnston, the Baldwins became supporters of Oberlin College and they were responsible for the majority of the money used to create Baldwin Cottage. The Baldwins lived in Cleveland and had made their money operating a very successful dry-goods store (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston; Memorial Record of the County of Cuyahoga and City of Cleveland, Ohio. Genealogical Committee, Western Reserve Historical Society, 1894. 117).

38In January of 1886, the Ladies Hall, the female dorm, burned down. Johnston, on a trip to accrue funds to rebuild, stopped at the home of her friend Mr. Baldwin in Cleveland, and he donated $20,000. According to her biographer, she described the visit thusly: “I did not mean to ask [Mr. Baldwin] for anything, but just tell the situation. I thought he might give something, perhaps a thousand dollars. He listened attentively to my story, said he had long been thinking of doing something for Oberlin, and without saying how much quietly wrote a check and handed me [sic]. When I saw how much it was, I was dazed. I had no words to thank him.” She also visited Solon and Mary Severance on this trip, and Mary Severance donated an additional $800 to furnish what would become Baldwin Cottage. Miss Gertrude Baldwin, E.I. Baldwin’s daughter, laid the cornerstone for the building in June of 1886. At Mr. Baldwin’s request, a suite of rooms was built for Johnston in Baldwin Cottage, and these rooms were to be her home as long as she remained an officer of the college (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston, 138-9).

39After the Ladies Hall burned down in 1886, it was decided that two buildings would be need to fill the void it left. With the funds already raised for Baldwin Cottage, Johnston, along with other faculty members went on trips to secure additional donations. The results of her trip are described in the 12 June 1886 edition of The Oberlin Review: “A telegram from Mrs. Johnston May 30 announces to us the welcome tidings that $20,000 has been donated by Mr. and Mrs. James Talcott, of New York, to be applied to the building of a cottage to take the place of Ladies Hall. Talcott Hall will certainly be the appropriate name for the new building. Although Mr. Talcott has never been in Oberlin, he is already known to us as the founder of the Talcott Scholarship for self-supporting young women.” Though it is not evident what precisely was Mrs. Johnston’s relationship with the Talcotts, her part in obtaining donations from them is clear (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston, 140).

40Lord Cottage was built due to a donation from Elizabeth Russell Lord (1819-1908). Lord was a widow who had become acquainted with Johnston in 1883, when she agreed to donate a small amount of money to help build Sturges Hall, on the condition that Johnston would meet with her personally. Johnston accepted gladly, and brought a number of the fourth-year students along with her for what was termed a successful visit. When Johnston’s Assistant Dean left unexpectedly in 1884, Johnston sought out Lord and asked her to take on the job. Lord accepted, and held that position quite successfully, until she retired alongside Johnston in 1890 (Johnston was only retiring as Dean, and maintained her Professorship). After a chance remark by Johnston, who felt that there should be a dormitory meant specifically to provide housing to the children of missionaries, Lord decided to donate 10,000 dollars, which she had been saving for a trip to Europe, to the college to create such a dorm. Johnston was easily able to obtain the rest of the money needed, and Mrs. Lord laid the cornerstone of Lord’s Cottage in 1892 (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

41 Dr. Dudley P. Allen (1814-1898) was a member of the Kinsman Academy Board of Trustees. Johnston was president of the Academy from 1862 to 1865 and met Allen, who was also the town physician, in that capacity. The two became good friends, and Johnston became close to the entire Allen family. According to her biographer Harriet Keeler, the Allens moved from Kinsman, Ohio, to Oberlin largely because of Johnston’s suggestion, and thus their various donations to the college can be attributed to her influence (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

42Johnston was initially able to travel to Europe because of some well-placed investments made by her husband. Later in life, she often traveled with friends, including the Warners, Baldwins, and Harriet Keeler, which may have defrayed some of the costs and allowed her to travel for longer than she would otherwise have been able to. Although Johnston never appears to have had great wealth, she was financially comfortable throughout her adult life (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

43Her travel accounts illustrate how evocative her descriptions could be. The following description of Spanish cathedrals is from her account entitled “Thirty Days in Spain.” It reads in part: “You may never speak with them, but you feel their presence, you meet them at every turn, the shadows of the good king and queen Catholic, haunt every cathedral of Spain, they glide out and in between the effigies of saints, and the statues of bishops and priests. It is Philip the II’s foot step that you ever hear behind you.” These vivid descriptions are also apparent in her travel account from Norway, which is included in this collection (Oberlin College Archives, Adelia A. Field Johnston Papers. Series III Travel Accounts and Diaries, 1862-1994 (span). RG 30/19).

44Johnston founded the Oberlin Village Improvement Society (OVIS) after her retirement from her Deanship, and focused on it a great deal once she was retired from teaching completely. The goal of the society was to beautify the city of Oberlin, and it was part of a greater movement in the United States that focused on improving both the sanitation and beauty of urban spaces. Letters concerning her efforts for OVIS from Frank Carpenter and Rebecca Johnson are included in this collection. (Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston; Barbara S. Christen, City Beautiful in a Small Town: The Early History of the Village Improvement Society in Oberlin. Elyria, Ohio: Lorain County Historical Society, 1994.)

45Plum Creek; Bradley misspells the name.

46The Community Parkway was a major project of Johnston’s. She obtained land along the banks of Plum Creek that was then made into parks, some of which still exist today (Barbara S. Christen, City Beautiful in a Small Town; Harriet Louise Keeler, The Life of Adelia A. Field Johnston).

47The Oberlin Arboretum is a large stretch of woodland owned and preserved by the College on the south end of campus.