Project Group: Frances Casey, Hannah Cohen, and Katherine Graves

Student Editor: Natalia Shevin

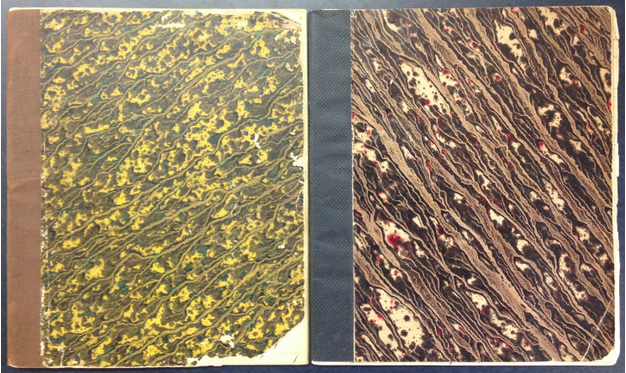

Emilie E. Palmer was born on 6 August 1842 in Windham, Ohio to Sheldon Palmer and Eliza Parks Gifford. Her two diaries of her time at Oberlin College are kept in this collection, along with their transcriptions typed by her granddaughter, Grace Loomis Battle. Palmer’s diaries are handwritten in black ink and pencil, thin, bound by string, and have dark marbled covers. They were written between 1859 and 1863, which incorporates her time at Oberlin from 1859 to 1861, and the Civil War which began in 1861; most of her life outside this time is unknown. After her death, Palmer’s granddaughter donated her two diaries to Oberlin College as historical documents.

Diaries comprise an important part of the historical record by providing first-hand accounts and intimate details of the lives of ordinary people. While the role of soldiers is emphasized in the study of the Civil War, the role of women away from the battlefield is not often acknowledged. Palmer wrote an informative account of a student in a small town reconciling herself with the sacrifices her community must make in the face of brutal conflict.

Christianity provided the moral foundation on which Palmer relied throughout her diaries. For Palmer, the answer to Mary Wollstonecraft’s query, “And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she know why she ought to be virtuous?” lay in religious education.1 Palmer’s relationship with God and the First Congregational Church in Oberlin provided her with guidance and the ability to cope with the turmoil of the Civil War, at least temporarily.

Despite Palmer’s commitment to Christianity and pride being a person of faith, when the war continued for longer than expected, the tone of her entries darkened. Many of her friends from Lorain County volunteered for Company C of the 7th regiment of Ohio, and some did not return. Dan Gould’s death in battle particularly affected Palmer.2 She grieved his death longer than that of her grandparents or any other death mentioned in her diaries. Although she clung to the belief that the endless war or her prospect for courtship would be remedied with time, Dan’s death tested her faith.3

The loss and hardship that Palmer faced were not an anomaly among homefront women. Helen Finney Cox, daughter of Charles Grandison Finney and wife of Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox described the roles of women in northeast Ohio in her essay, “Women’s Share in the Civil War.”4 Cox’s shared position with Palmer as a young white woman in Oberlin makes her essay pertinent to understanding Palmer’s experiences. Written in 1891, Cox reflects on how women adjusted to the demands of the homefront, such as rationing luxury items like canned fruit and butter, as well as assuming new roles like farming and nursing. Clergymen encouraged women to participate by speaking of “the duty of the hour; the need not only of strong hands, but of brave hearts at home, to send the men into the field cheerfully, and to hear patiently whatever might betide their absence.”5 Just five days after President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteer Union soldiers, Cleveland women created the Soldiers’ Aid Society of Northern Ohio. They were also quick to participate in other organizations, such as the Women’s Aid Society, Department of Nurses, U.S. Sanitary Commission, Freedman’s Bureau, and Union volunteer refreshment saloons.6 Even as men were going off to join the Union regiments, women were also making valiant sacrifices for their country. Cox affirmed this, saying “To each one of that great company of women, bearing their daily martyrdom with fortitude and resignation, shall not the plaudit be given: ‘She hath done what she could?’”7

Palmer stayed within northeast Ohio for the time of the Civil War, traveling only as far as Kingsville, Ohio, 100 miles from Oberlin, to be a teacher. Although varying by region, season, and decade, teaching was the primary employment for women during Palmer’s lifetime.8 The mother’s role in raising boys to be patriots, her ability to nurture and teach, was recognized. Despite the assumption that women’s expertise in teaching came from their natural ability to work with children, many women taught in order to postpone, or even altogether reject, childbearing responsibilities.9 Although young female teachers were likely seen as traditional in their pursuits, their potential was subversive. For many, teaching rescued women from domesticity, providing them with a community of like-minded women.10

Palmer’s positive experiences pursuing higher education at Oberlin College prepared her for, and likely influenced, her decision to teach. The importance of education is is argued in Sarah Grimké’s “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes.”11 She wrote, “One of the duties which devolve upon women in the present interesting crisis, is to prepare themselves for more extensive usefulness, by making use of those religious and literary privileges and advantages that are within their reach, if they will only stretch out their hands and possess them.”12 This frame of mind was echoed in Palmer’s life as she embraced her academic and religious opportunities at Oberlin College. She was especially inspired by theological teachings from Oberlin faculty and lectures on religious tolerance and travels by missionaries.

In 1868 Palmer married Julius Fitch Loomis in Ohio at age twenty-six, later than most women her era. Her decision to pursue education, coupled with the influence of the Civil War, may have resulted in her marrying at an older age. After marrying Loomis, the couple moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Palmer only bore three children: Edward Percy, Jesse Alice, and Sheldon Palmer. She embraced changing familial trends of the period.

Emilie Palmer Loomis was active in numerous organizations in Chattanooga, including the Vine Street Orphan’s Home, the Second Presbyterian Church, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, and the Florence Crittenton Home. Little more is known about her time in Chattanooga. She passed away on 26 December 1931 in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Palmer’s diary is integral to understanding the impacts of war, faith, and education on a young, white, middle-class woman. Though Palmer herself rarely acknowledged slavery and abolitionist movements in her diaries (with the exception of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue) she would have been exposed to abolitionist thought during her time at Oberlin College. Palmer’s exposure to theology and her participation in First Congregational Church aided her maturation into womanhood, as she dealt with issues of morality, religion, and interpersonal relationships. These universal coming of age struggles are uniquely filtered through the lense of the turbulent time in which Emilie E. Palmer lived.

1Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, originally published 1792 (University of Virginia Library, 2010), 2.

2Likely Daniel C. Gould, enrolled at Oberlin College between 1835 and 1836, from Springfield, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the 105th regiment during the Civil War. (Lostli. Regiment OHIO VOLUNTEER INFANTRY. Web address, accessed 1 July 2015).

3In Palmer’s 29 June 1862 entry, she writes that “just one thought” occupied her mind, insinuating that she hoped their correspondence would become a courtship. (29 June 1862, Emilie E. Palmer Diary).

4 Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875) was an American Presbyterian minister, and a leader in the Second Great Awakening. He taught at Oberlin College starting in 1835, and served as president from 1851 to 1866; Jacob Dolson Cox (1828-1900) was a high-ranking official in the army. Cox graduated from Oberlin College in 1850, but left his graduate studies in Theology in 1851 after a dispute with Finney. Although before the Civil War he was an abolitionist, he opposed the 15th Amendment which would guarantee African American suffrage (“Jacob D. Cox – Ohio History Central.” Jacob D. Cox – Ohio History Central. Web address, accessed 01 July 2015); Helen Finney Cox, “Woman’s Share in the Civil War.” 1891. Cochran Family Papers, RG 30/8, SG 2, Series 6, Subseries 3, Box 3, Oberlin College Archives.

5 Helen Finney Cox, “Woman’s Share in the Civil War,” 1.

6 Palmer’s life spoke to the duty clergymen put forth of having “brave hearts at home” by writing frequently to her friends at war. However, some women traveled to aid with efforts of the newly established Freedman’s Bureau in 1865. By straying from socially sanctioned occupations they were sometimes met with resistance. Josephine Griffing, a white woman who organized in Ohio before moving to Washington D.C. to aid freed people was one of those women. O.O. Howard, the Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, rewarded her dedication by appointing her assistant commissioner in Washington D.C. However, Jacob R. Shipherd, the author of The History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, wrote to Howard, warning him of what he believed to be Griffing’s deluded organizing; “Mrs. Griffing is hopelessly unfit for the responsible position she fills, & cannot be too permanently separated from it.” Shiperd believed asking for assistance for newly freed African Americans was too much, and would create enemies of those who supported emancipation. Although Shipherd writes applauded the bravery of the Rescuers of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, his opinions of Griffing highlight the shortcomings of his understanding of both women’s rights and full emancipation of African Americans. (Letter from Jacob R. Shipherd to O.O. Howard, 30 October 1865, Office of the Commissioner, Letters Received, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, M752, RG 105, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Web address, accessed 1 July 2015).

7 Helen Finney Cox, “Woman’s Share in the Civil War,” 1; Mark 14:8.

8 Robert A. Margo and Joel Perlmann, Women’s Work?: American Schoolteachers, 1650-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 1.

9 Rachel Hope Cleves, Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 29.

10 Rachel Hope Cleves, Charity and Sylvia, 27.

11 Sarah Grimké (1792-1873) was a lecturer and writer on abolition and women’s rights.

12 Sarah Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 121.