Project Group: Kristin McFadden, Leah Newman, Camille Pass

Student Editor: Natalia Shevin

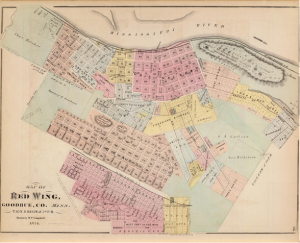

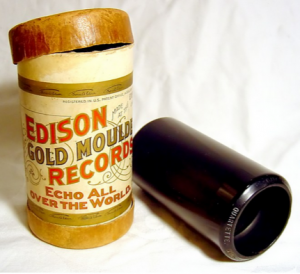

Frances Theresa Densmore was born in Red Wing, Minnesota, in 1867, to a successful pioneer family. Her grandfather, Judge Orrin Densmore, was one of the first settlers of Red Wing; her father, Benjamin Densmore, was a civil engineer; and her mother, Sarah Adelaide Greenland Densmore, was active in the community. She studied harmony and keyboard from a young age, enrolling in the Oberlin Conservatory from 1884 to 1887 to study piano, organ, and harmony (music theory). After Oberlin, Densmore became an acclaimed ethnomusicologist due to her study and preservation of Native American music. Her career stemmed from her childhood exposure to and curiosity about the music of the Sioux Nation, as her Episcopal Church was involved in the Native American communities under the leadership of Bishop Henry Wipple. He sought to meet their spiritual and physical needs and train leadership, but his church ultimately served as an assimilationist force.1 Densmore’s interest grew in 1893 when she visited the Chicago World’s Fair and read A Study of Omaha Music by Alice Cunningham Fletcher.2 Densmore used wax cylinders to record Native American music through the Smithsonian Institute’s Bureau of American Ethnography. She received an honorary Master of Arts degree from Oberlin in 1924, and an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters from Macalester College in 1950.

This mini-edition focuses on a specific time in Densmore’s personal history that precedes her work as an esteemed ethnomusicologist. Frances Densmore’s collection in the Oberlin College Archives is comprised of letters to her family in Red Wing, music notation books and class notes, and sketches she created during her time at Oberlin.

Densmore was not interested in literary societies, moral reform, or Christianity like other Oberlin women in her era.3 She wrote, “I hardly think I shall join one of the Literary Societies, not till winter any way for I am so busy and it costs $5.00 at first and society taxes afterward.”4 In later letters, Densmore expressed her lack of interest in the Young Ladies’ Missionary Society and Ladies’ Prayer meeting, which most people saw as appropriate women’s work. Perhaps Densmore’s Episcopalian upbringing explains why she was uninterested in the evangelical ideology prevalent at Oberlin. Moreover, at a time when young women gained literary and oral skills through clubs and societies at Oberlin, Densmore spent her time perfecting her skills as an organist and pianist. In many of her letters, she describes concerts she attended and lessons she had, particularly with Lucretia Celestia Wattles.5 Densmore’s strong relationship with women faculty and professors at Oberlin were not only an aspect of New Women, but likely inspired her to pursue a challenging profession herself, one in the sciences.

Densmore’s letters show how she became so invested in her profession in a field rarely pursued by women. Caroll Smith-Rosenberg writes that the New Woman “eschewed marriage, fought for professional visibility, espoused innovative, often radical, economic and social reforms, and wielded real political power. At the same time, as a member of the affluent new bourgeoisie, most frequently a child of small-town American, she felt herself part of the grassroots of her country.”6 Although Densmore did not fulfill all of the criteria laid out by Smith-Rosenberg, her decision to pursue anthropology through government-funded institutions and create her own archive exemplifies the commitment she had to claiming her place in academia and public professions.

In a letter to Charles Hofmann, a student and close friend of Densmore’s, she wrote, “At the Oberlin Conservatory of Music I met ‘interesting people’ from many lands and learned to feel at home with Chinese, Japanese, Negroes and girls from Micronesia. This atmosphere was cosmopolitan and a preparation for thirty tribes of Indians.”7 She also studied Haydn, Bach, and Handel, among others, as seen in her class notes, which framed her work with Native Americans. In the coming decade, Densmore would write in letters that she viewed the music of Native Americans as “primitive” in contrast to composers she studied at Oberlin.8 This rhetoric casts her in the moment of an evolving racial ideology that relied on scientific justification for, in this case, the continued colonization of Native Americans.

Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

Densmore recorded songs at a time when Native American culture was being eradicated by the United States government. Singing and dancing in particular were explicitly regulated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The goal was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society. For example, the Carlisle Indian Training and Industrial School was founded by Richard Henry Pratt, a US colonel, in 1879 that “refashioned [young Native Americans] as a member of mainstream American society.”9 Dance and religious and medicinal ceremonies were especially targeted under the Civilized Regulations of 1880, which was particularly relevant to the work of Densmore. Only Native Americans could commit these offenses, which remained legal until 1936. Although Densmore fashioned herself as an objective “lone white person” proud to assume the task of “authentic” preservation, Native Americans were frequently hesitant and sometimes outright opposed to her presence (and that of other anthropologists), given the history of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ acting in opposition to the interests of Native Americans.10

In some cases, Densmore coerced singers into recording for her by compensating them with goods and money. The poverty on reservations created a situation in which many Native Americans could not refuse Densmore’s offer, making her work exploitative despite its archival impact.11 In 1947, Densmore reflected on a 1907 visit to a Chippewa reservation in Minnesota for a celebration, saying that “more white people were in attendance and the gathering was changing from a tribal occasion to an exhibition, with a political significance.”12 In fact, Densmore’s methods preceded the development of a tourist economy for Native Americans, a culturally extractive practice created by the destitute conditions of reservations and the voyeurism of white Americans toward Native American culture.

Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

Further complicating Densmore’s legacy was her obsession with cultivating an archive of her work in a male-dominated field. She was aware that she would influence future women anthropologists, so she was particular about how institutions saved her recordings, letters, and manuscripts. She was also aware of the limits of whiteness, citing both her personal letters and published manuscripts. In Indian Action Songs she wrote in the introduction to “The Approach of the Storm, “It is impossible for a white person to understand the full significance of tobacco and smoke to the Indian.”13 On the radio she described the pine trees and night skies, saying “to me it was picturesque but the Chippewa felt so much more than it is possible for a white person.”14 But ultimately Densmore’s commitment to the accuracy of her records and her legacy was more about saving herself than using her proximity to the American government to fight for decolonization, as Helen Hunt Jackson did.15

Densmore’s work was groundbreaking at a time when the United States government pursued the eradication of Native culture with militancy and ubiquity. Her work as a scholar to preserve song, dance, and stories of Native Americans occurred long before the government took interest in the 1930s, under the policies of the Indian Reorganization Act. Her contribution to Native Studies, Anthropology, and Women’s Studies cannot be understated, despite the complicated nature of her work.

Densmore spent the last twenty years of her life preserving her legacy, as seen in the documents transcribed here. In 1884, she wrote the originals of the letters in this edition on thin wax paper. They are now covered in tape and mangled together, or pasted onto copy paper with captions and contextualized with parentheticals. Densmore later transcribed her own letters using her typewriter so that they were legible before donating them to the Oberlin College Library in 1941. The transcriptions in this edition are based on Densmore’s typewritten copies, which include pen markings where Densmore corrected her work.

Pencil additions by Densmore are notated by “< >.”

1For an example of Densmore’s assimilationist orientation, see her account of Pauline Colby, a missionary on a Chippewa reservation who taught Sunday School for Native Americans. Densmore writes, “She saw the Chippewa advance in the religion of the white man, in their long journey from the primitive religious of their forefathers” (Frances Densmore, A Missionary Journey in Minnesota in 1893, related by Miss Pauline Colby to Frances Densmore, Frances Densmore papers, Minnesota Historical Society; See also Joan M. Jensen and Michelle Wick Patterson, eds. Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 34).

2In the program for a lecture-recital Densmore gave in 1904 on “The music of the American Indian: An Interpretation of America’s first Music,” Fletcher endorsed the program, saying, “Your years of unswerving fidelity to this music proves your appreciation of its value and only one who has appreciation is entitled to undertake the task of presenting it to others. Your honesty and faithfulness in the labor of bringing before the people of these American wildflower of song has been proved, and I commend you in the task you have undertaken.” (Frances Densmore: Sketches made in Oberlin of places where she lived, people and scenes, Record Group 30/156, O. C. A).

3For more information, see “Education is as needful to the lady as to the gentleman”: The Papers of Mary Sheldon and Heartache from the Home Front: Emilie Palmer’s Diaries 1859-1863. Though these women attended Oberlin before Densmore, they typify a more characteristic relationship to the College even in Densmore’s day.

4Letter No. 28, Frances Theresa Densmore Letters 1884-86, Record Group 30/156. O. C. A.

5Lucretia Celestia Wattles (1849-1933), professor of pianoforte (piano) and harmony (music theory) at Oberlin Conservatory from 1871 to 1892.

6Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 245.

7Charles Hofmann and Frances Densmore, Frances Densmore and American Indian Music; a Memorial Volume, Contributions from the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, v. 23 (New York: Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, 1968), 1.

8Frances Densmore Notebooks, Record Group 30/156, O. C. A.; Minnesota Public Radio, “Densmore’s Attitude Towards Indians,” Web address, accessed 5 August 2015. Original citation: Densmore: The Music of the American Indians, typescript for lecture before the Anthropological Society of Washington, 26 April 1909, Densmore Papers, National Anthropological Archives.

9Public Broadcasting Service, “Events of the West 1870-1880,” The West Film Project, 2001, Web address, accessed 7 August 2015.

10Jensen and Patterson, Travels with Frances Densmore, 30.

11Jensen and Patterson, Travels with Frances Densmore, 73.

12Frances Densmore, Prelude to the Study of Indian Music in Minnesota, Frances Densmore papers, Minnesota Historical Society.

13Frances Densmore, Indian Action Songs; a Collection of Descriptive Songs Of the Chippewa Indians, with Directions for Pantomimic Representation in Schools and Community Assemblies (Boston, MA: Birchard, 1921), 2.

14Frances Densmore, Chippewa Stories and Industries, Radio talk No. 3, 9 March 1932, Frances Densmore papers, Minnesota Historical Society.

15In 1881 Jackson wrote A Century of Dishonor in which she described the detrimental effects the United States government had on Native Americans. Jackson was in a similar position to Densmore as a middle-class, educated white woman. Densmore had the opportunity to advocate on behalf of Native Americans when Red Cap of the Ute tribe refused to sing for her, but asked to record a message for the Indian Commissioner in Washington. He sought to get rid of the agent (former name of the Superintendent of an Indian Reservation). Densmore wrote in a memoir which she sent to Charles Hofmann, “About six months later I kept my promise to Red Cap and played the record for the Commissioner, explaining that I had absolutely no responsibility in the matter. He was accustomed to the ways of Indians and I had kept my promise to an Indian singer” (Charles Hofmann and Frances Densmore, Frances Densmore and American Indian Music, 41).